- Bomberman Series Introduction / Bomberman (1983)

- 3-D Bomberman

- Bomberman (1985)

- RoboWarrior

- Atomic Punk

- Bomberman (1990)

- Atomic Punk (Arcade)

- Bomberman II

- New Atomic Punk: Global Quest

- Bomberman ’93

- Super Bomberman

- Hi-Ten Bomberman / Hi-Ten Chara Bomb

- Bomberman ’94 / Mega Bomberman

- Super Bomberman 2

- Super Bomberman 3

- Wario Blast: Featuring Bomberman

- Bomberman GB 2

- Bomberman: Panic Bomber

- Super Bomberman 4

- Saturn Bomberman

- Bomberman GB 3

- Bomberman B-Daman

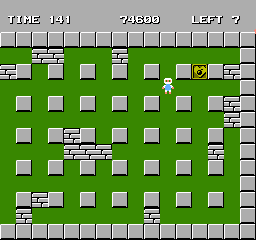

In the year 1985, all it took was one grueling 72-hour programming session to change the fate of Hudson Soft and Bomberman forever. Shinichi Nakamoto, the man behind it all, found the original 1983 game in Hudson Soft’s library and decided to bring it to the Famicom, since Nintendo’s popular console looked to be the best way to maximize Hudson Soft’s fortunes after the success of Lode Runner. Calling it a port would be a disservice though, since Nakamoto drastically revised the game to make it more marketable and add enough mechanical depth to have it compare favorably to its contemporaries.

Suffice it to say, Nakamoto’s idea paid off big time and Bomberman was tremendously successful, selling nearly a million copies according to the box art used for the game’s release in the west four years later. The success of Bomberman helped propel Shinichi Nakamoto’s career within Hudson Soft as well, resulting in him being promoted to company director in 1986, director of R&D in 1995, and executive vice president in 1999. Nakamoto would also go on to help design other titles in the series, such as Bomberman ’93 and Mega Bomberman.

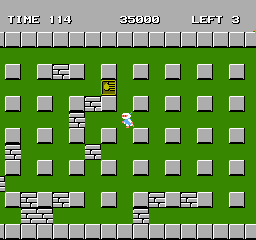

Feeling that the designs of the original 1983 game were too plain and unappealing, Nakamoto looked to his previous work, Lode Runner, for inspiration. Bomberman’s now-iconic design was taken from the robotic Bungeling Empire guards that appeared in the NES version of Lode Runner, and that game’s more cartoonish look would go on to be the driving philosophy behind Bomberman’s visuals as a whole. This particular installment is also tied to the Lode Runner canon – Bomberman is put to work at an underground bomb factory and decides to escape after hearing a rumor that anyone who makes it to the surface will become human. Once you’ve made it out of the factory after clearing all 50 levels, Bomberman ends up becoming the Runner, establishing this game both as a prequel and as the first Bomberman game to have an ending.

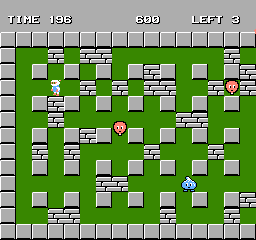

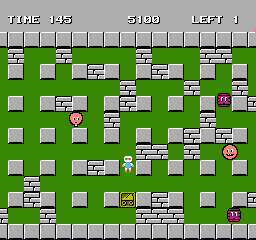

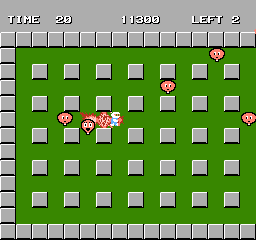

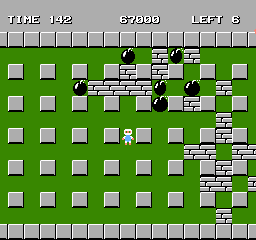

Realizing that the balloons alone weren’t enough, there’s now a whole menagerie of foes to deal with, each with their own style and strategies. The blue, amoeba-like Doria, for example, moves very slowly but can pass right through soft blocks, making it hard to catch depending on the layout of the maze. Some foes are aggressive and tend to fixate on Bomberman, like the coin-shaped Pontan, whereas others like the barrel-shaped Dahl prefer to follow repetitive patterns regardless of your position. Each foe has unique animations for movement and for when they’re blown up, giving the game a lot more personality than the previous entries. Having to recognize and prepare for different opponents ultimately makes for a far more interesting game that does a solid job of selling the appeal of single player Bomberman – finding satisfaction in devising the perfect traps and strategies for a wide variety of foes while learning how to avoid their tricks.

This is also the first game in the series to have proper music, courtesy of Jun Chikuma. As her first composition, it’s relatively simplistic, with the same song playing for all 50 stages (bonus stages get a different track at least), but it was catchy enough to become one of the main themes for the franchise as a whole, and the jingles that play when you clear a stage or die are similarly iconic. The main track also changes to a more upbeat, triumphant version once you’ve collected the power-up in the current level, which serves as a clever flourish to further empower and reward the player for their thoroughness. Chikuma would go on to define the sound of the franchise’s main installments all throughout the 90s and her compositions improved drastically over time, culminating in the excellence that is the Bomberman Hero soundtrack.

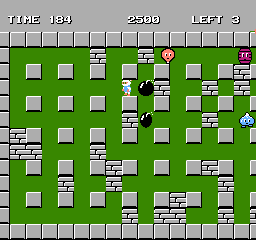

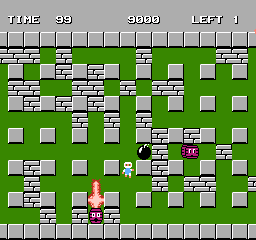

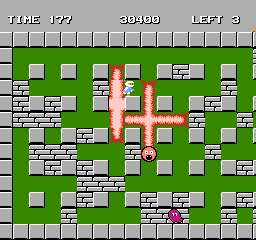

The fundamentals here are unchanged, but there are a host of improvements in every facet of the gameplay. Bomberman himself feels significantly tighter to control thanks to the removal of half-space movement, which allows for finer control when turning corners and makes it easier to place bombs accurately. Your enemies are now consistent in their behavior and nobody can pass through bombs by default this time around, making it easier to plan around your foes’ movements and shake off pursuers. Levels are big enough to scroll horizontally and there’s plenty more soft blocks to clear out as you go. All of this contributes to a slower, more methodical game on paper, but thanks to the introduction of a timer, things remain as tense as ever. You’re given 200 seconds to clear a stage, a limit you’ll frequently bump up against since you have to clear out every enemy and then search for the exit hidden beneath the soft blocks. Running out of time isn’t necessarily a death sentence, but it does summon an abundance of additional foes that could easily ruin an otherwise successful run.

Bomberman starts off as weak as possible this time, with only one bomb available and the lowest amount of firepower possible. This makes defeating even the most basic enemies troublesome at first, but the tables can be turned thanks to the introduction of power-ups. Taking notes from contemporary shoot-em-ups like Star Force, each level now has a single power-up to be found in one of the many soft blocks strewn about. These will usually be upgrades to your bomb quantity or firepower, but there are also power-ups that assist in mobility, such as the ability to walk through bombs and walls. The biggest game changer of them all though is the remote control, which allows you to decide when your bombs explode with a press of the B button. The inverse difficulty curve feels strange at first, but it’s worth the struggle once you’re blazing through levels in a matter of seconds with bundles of massive explosions created entirely at your whim.

Scoring is no longer the focus of the game, but items that exist solely for points do make a return, and in a more interesting manner to boot. Likely inspired by the Japanese phenomenon that was 1984’s Tower of Druaga, each level has an incredibly obscure condition that can be fulfilled in order to earn a special item for points. These conditions are basically impossible to figure out on your own, and even when you know what needs to be done, it can be actually impossible to fulfill them based on the layout of the level’s soft blocks. Some of these conditions include clearing out the stage’s enemies without destroying a single soft block, walking over the exit and then holding a single direction for 15 seconds before killing anything, and intentionally blowing up every soft block and the exit three times while avoiding the enemies that pop out of it as a punishment for doing so. These items are mostly references to things related to Hudson Soft, such as Dezeniman-san from Dezeni World, the bonus target icon from Star Force, and even Shinichi Nakamoto himself.

The concept of alternate level types returns from the MSX and ZX Spectrum versions of the original game, though thankfully it’s no longer in the form of the Bomb Auto Setting stages. Every five levels, you’ll be brought to a bonus stage where your goal is to blow up as many enemies as you can in a short time. You’re invincible during these stages and there’s no soft blocks to obstruct you either, so they’re basically ways to let off some steam and earn a bunch of extra points, which now have more value thanks to the introduction of earnable extra lives.

Losing all of your lives doesn’t kick you back to square one this time since there’s now a password system that retains your progress. The passwords are pretty tedious to enter due to their length, but they make the 50 levels a lot less daunting to tackle and the fact that they preserve most of your power-ups prevents the player from getting stuck with an under-powered Bomberman during the later stages. The system itself is rather buggy though, since it’s possible to create passwords that bring you to unintended stages beyond the initial 50, each with their own potential glitches and issues. As a cool bonus, it’s also possible to find passwords for three special stages that are designed to provide a significant challenge by restricting your starting capabilities in the face of hordes of enemies.

Despite the gap between the two, the NES version isn’t too different from the original Famicom version. Aside from an adjustment to the title screen, specifically the removal of the border surrounding the title and a bit of extra copyright text, the only other notable difference is that the ending of the NES version has slightly more text. The Famicom version outright tells you that Bomberman has become the Runner, but the NES version instead says that Bomberman has become a human and asks you to figure out which Hudson Soft game he’s in. There was also a version released for the Famicom Disk System in 1990, which disappointingly does nothing to take advantage of the disk format. Passwords are still present and the game is otherwise identical, implying that this was a quick and dirty budget release meant to be utilized at disk writer kiosks in Japan.

Perhaps in an attempt to further sweepBakudanOtoko under the rug, Bomberman was ported back to the MSX in 1986 as Bomberman Special. It’s mostly the same game, but with some compromises made to accommodate the MSX hardware. Enemies have less animation, levels are now broken up into distinct segments instead of scrolling smoothly, and the game in general is a bit slower. Everything is a different color in this version, primarily using a somewhat garish combination of blue, green, and gray. Beyond these changes, all of the features of the Famicom game are present here, making it a respectable port overall.

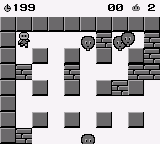

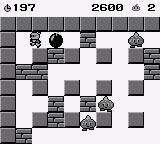

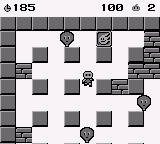

The first portable version of Bomberman would arrive on the Game Boy packed in with 1990’s Atomic Punk as the “Game B” mode. It’s a full port, containing all 50 levels and the rest of the content from the original game. The one place where this port is compromised is exactly where you’d expect – to accommodate the smaller screen, the game is significantly zoomed in, greatly limiting your view of the level at all times. Soft blocks appear in far smaller quantities here as well, creating situations where it can be difficult to corner enemies because of all of the open space.

The most obscure version of the game would have to be the one released in 2001 for Palm PDAs and mobile devices. This version has several audiovisual differences, including a different title screen, redone sprites suited to the displays of Palm devices, and a new ending that removes the Lode Runner connection and replaces it with a brief congratulatory screen. Jun Chikuma’s composition was replaced with a new soundtrack that’s a notable downgrade, exchanging the iconic Bomberman tracks with an extremely short loop of beeps that are unpleasant to the ears. Between the various downgrades, the sluggish gameplay, and the awkward controls, it’s hard to justify bothering with this version for any reason beyond curiosity.

Bomberman was chosen as one of the third party titles to be re-released for Nintendo’s Classic NES Series (and Famicom Mini) line for the Game Boy Advance in 2004. Like many ports on the GBA, everything looks a bit squished to compensate for the screen size and the colors are slightly brighter as well. Most notable about this version is the ability to save your passwords, allowing you to pick back up without having to manually enter the password. It’s a small difference, very much in line with the minimalist approach taken with the Classic NES Series/Famicom Mini line, but one that’s convenient enough to make a case for this version over the other ones. Bomberman was also included in a 2005 GBA compilation by the name of Hudson Soft Best Collection Vol. 1, something that remained exclusive to Japan. The rest of the world didn’t miss much though, since it’s just a straight port of the Famicom version without the save feature added to the Classic NES Series/Famicom Mini version.

As one of Bomberman’s many forays into mobile gaming, 2007’s Bomberman Reprint was a return to 1985, featuring both the original game (mostly) as it was alongside an “Arrange” mode that makes more significant tweaks. In the Arrange mode, everything is updated to have a 16-bit look, and the UI now features information on which power-ups you currently have. The floor changes color every so often as you progress, adding some welcome visual variety. Classic mode redraws Bomberman’s Famicom sprite to look strangely massive compared to everything else, but is otherwise the same as the original game. Like many mobile games, this one unfortunately never left Japan.

Bomberman is a massive improvement over the previous two games, and while it could easily be seen as quaint by today’s standards due to its repetitive nature, it still holds up remarkably well as the thesis statement for the franchise’s single player modes. So much so, in fact, that the previous two games are now completely disregarded by most, including Nakamoto himself, who is on the record as saying that he considers the Famicom version of Bomberman to be the one true version of the original game. Even with all its success, this game was just half of the future Bomberman formula, since it’s still missing one very important thing – the multiplayer! Despite being synonymous with the Bomberman name, multiplayer still wasn’t included with this entry and wouldn’t become a part of the series until 1990, which would also serve as the beginning of a fruitful run on the PC Engine.

Links

http://bomberpedia.shoutwiki.com/wiki/Glitched_stages_in_Bomberman_(NES) – List of all the glitched password stages plus the three special stages

https://tcrf.net/Bomberman_(NES) – Shows all of the obscure bonus items you can find

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPX3yrLPG2A – Video of the Palm OS version

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NznkpiGF1BQ – Video of Bomberman Reprint’s Classic Mode

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrGxu-M3b68 – Video of Bomberman Reprint’s Arrange Mode

http://bomberpedia.shoutwiki.com/wiki/Shinichi_Nakamoto – Information on Shinichi Nakamoto