- Worms

- Worms: Reinforcements

- Worms: The Director’s Cut

- Worms 2

- Worms Pinball

- Worms Armageddon

- Worms World Party

- Worms Blast

- Worms 3D

- Worms Forts: Under Siege

- Worms 4: Mayhem

- Worms: Open Warfare

- Worms: Open Warfare 2

- Worms 2 – Armageddon / Worms Reloaded

- Worms: A Space Oddity

- Worms: Battle Islands

- Worms Crazy Golf

- Worms Revolution

- Worms Rumble

Confusingly, this isn’t actually the Director’s Cut — that comes later.

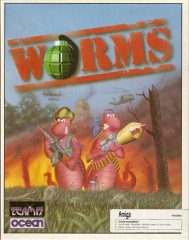

For those of us who live outside of Europe, the region where it reigned supreme, the Commodore Amiga is a land of mysteries. With a much smaller user base, players in the United States only got the occasional glimpse at its unique titles. There’s one clear exception, however, a series that not only managed to break free from Commodore’s sinking ship, but managed to carve a respectable niche for itself that persists to this game. While never quite as iconic as the likes of Pac-Man or Space Invaders, the Worms series somehow manages to remain near omnipresent enough to stand with the likes of those far more well-known franchises.

The titular worms themselves are tiny-sprited, squeaky-voiced creatures who amble around the environment, using various tools and weapons to deform the environment around them. One could consider the series the antithesis to Lemmings, giving they both involve giving various tools to cute British animals to achieve your ends. Indeed, the series spawned from a prototype where Psygnosis’s characters took up weapons and waged war upon another. While that prototype seems to be forever lost, contemporary reviewers didn’t miss the similarities. While Psygonsis’s games were about solving puzzles, however, Worms is almost always about blowing your enemies away with a wide variety of wacky weapons. Typically, although with notable exception, in turn-based, side-scrolling artillery combat.

The games lack any sort of overarching plotline, nor do they contain any recurring characters – unless you count the worms themselves as one singular entity. That isn’t to say that’s a particular fault, as such a thing would only muddy the game’s sense of slapstick and distinctly British sense of humor. Later games in the series offer single player campaign modes, but these serve more as flimsy excuses to bring you from map to map, with some goofy cutscenes and voiceover as a bonus. Whatever single player content the games offer usually only serves as a bonus to the game’s real draw, however – the multiplayer. While which game in the serves this purpose the best is a question of debate, the series by nature is typically held in high regard when it comes to multiplayer antics.

To be truthful, many of the games in the series take off from the idea introduced on the Amiga, adding, removing, and tweaking various additions as the series passes. This means that once you have an idea on how one game works, you can generally carry the knowledge to games following and preceding. It’s because of this fact that each game can generally be measured by what it does or doesn’t do compared to the 1995 original. With such a long running series, however, there are plenty of spinoffs to shake things up, most of which are enjoyable in their own right. Not to mention a boggling amount of ports and re-releases to dig through.

While there may be far better entry points in the series, truthfully, you could do far worse than the original game. While it’s light on content and is missing a multitude of features that would come to define later games, it’s still an enjoyable game on its own merits. It also serves as the template that every other mainline game in the series would follow after – if you can come to grips with this game, most of the series should fall in soon afterwards. Certain quality of life adjustments and minor tweaks have made their way in since 1995, to be sure. A well-used shotgun, however, remains as timeless as it ever did.

At its most basic of levels, Worms shares a similar concept with previous pioneers in the “artillery” genre, such as Scorched Earth and Gorillas. Using various weaponry, it’s up to you to determine the best speed and launching power with which to fire projectiles, trying to land a hit upon your enemy before they can do the same to you. Any projectiles that miss will likely take a chunk out of the randomly generated landscape, potentially removing whatever cover advantage your opponent might have begun with. After you take your shot, it’s then the next turn of the next player in line, the process repeating until only one player remains. What Worms really does to revolutionize this entire concept, however, is to put the weapons into characters with hands with which to hold them. Perhaps more importantly, they’ve also been given a lower half to maneuver through the maps themselves.

The worms under your control are capable of free movement during your turn. However, their inching can be painfully slow, and under the pressure of the turn clock, you might not be able to reach your destination in time. Worms can also leap in a short horizontal arc, which while certainly a faster way to travel, can’t be altered in any way. While it’s good for faster movement and clearing small gaps, care needs to be taken not to leap yourself right into a potential hazard. While it sounds like a minor feature in retrospect, it’s the ability to place yourself wherever you wish to line up the perfect shot that lends Worms so much of its strategy.

Once you’ve come to terms with this new dimension of gameplay, your objective is clear – kill all enemy worms before you yourself are destroyed. Up to four teams of four worms each are randomly placed upon a randomly generated map – including, at times, places where they almost certainly can’t do any damage without help. Each turn, you gain control of one of your worms, and your turn ends when you use a weapon, take damage, or run out the turn clock. Play then moves to the next team, until the time when play cycles to a different worm on your own team. The last team that remains alive after all others are eliminated take the round, with a best 2 out of 3 format by default.

Four teams of worms placed on a pristine, freshly drawn map.

To accomplish this, you’ve got to become familiar with your weaponry. Previous games in this style featured a single projectile that launched in an adjustable arc, with Scorched Earth offering a multitude of effects once it landed. In Worms, this takes the form of the classic bazooka, with which its infinite supply you’ll be dealing a majority of the damage you inflict. It isn’t the easiest of weapons to get used to, however – first you’ll need to get your worm into position, line up the angle, account for the way the wind might push your shell, and then hold down the fire button until you’ve built up just the right level of power. If you do it right, you can land a direct hit from massive distances away. Do it wrong, and you’ll blow up a chunk of the land, if you’re lucky – if not, your projectile might just do a 180, hit a teammate, or hit the ground right in front of you.

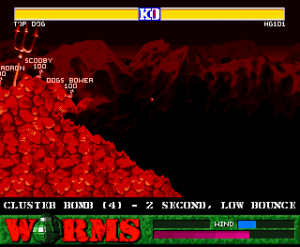

All worms also come equipped with an endless supply of grenades that they chuck. These can be even tougher to use properly, since they have all the factors of a bazooka shell, plus an adjustable explosion timer and a level of ‘bounciness’ that can be set. The added complexity comes with the advantage that they don’t explode immediately, letting you make trick shots and hit targets the bazooka never could. While they aren’t quite as reliable as a plain old bazooka shell, grenade mastery leads to seemingly impossible shots become within your grasp, reaching places your opponents were certain they were safe. Sometimes, however, a lucky guess can work all the same.

A difficult shot that just might hit its target.

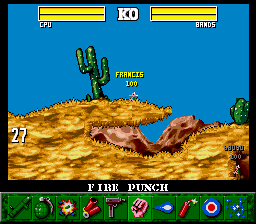

Bazookas and grenades aren’t all you’re limited to, however, as there’s an assortment of different weapons to master, each with their own particular uses. The shotgun has a short range, but lets you get in two attacks per turn, potentially offing two opponents in the right circumstances. The “Fire Punch” and “Dragon Ball” are most flagrant violations of Capcom’s copyright, but are useful for knocking opponents in a vertical arc or straight horizontally, respectively, potentially putting enemies right where you want them. The blowtorch and drill aren’t quite as damaging as more conventional weaponry, but are custom made for burrowing forwards and downwards to relative safety. Perhaps most powerful of all is the mighty airstrike, which can be used once per round to slam a small horizontal area with bombs – perfect for ruining tightly packed groups of worms.

Some weapons aren’t accessible right away, having a delay of a few turns before they become part of your kit. Others can only be found within crates that occasionally airdrop onto the field, giving the first team to collect them their heavy firepower – unless they’d rather just blow the crate up and use the explosion to cause the other team further harm. You might find an ordinary sheep, which can be sent out to trot harmlessly along the ground – until you decide when to remotely detonate it. The prod gives another worm a light shove – harmless, assuming there’s not a land mine or a deadly drop in their way. Most devastating of all is the banana bomb, a yellow fruit thrown like a grenade that splits into smaller bananas, each of which creates a massive explosion.

This crate might be just what you need to turn the tide of the battle.

Some of your arsenal don’t serve as weapons, but can be just as vital for your strategy as anything else. Worms can use their turn to teleport anywhere in the map, which is great from escaping a bad situation or placing themselves where the action is. Girders can be placed to cover gaps and serve as platforms, or provide temporary cover to defend against enemy fire. Items like these only have a limited number of uses, however, which means that knowing when and where to use them is just as vital as good aim. Also included amongst your arsenal are the options to give up your turn, as well as the game. Much more exciting is the kamikaze – launching a worm forward at high speed, tearing through ground and knocking worms away before they give their life in one final explosion.

Perhaps the most versatile tool of all Is the “ninja rope”, which can be fired out to any surface above your worm. On paper, it’s meant to be used to swing across gaps and carefully lower yourself from a high up position. With the right conditions and enough of an overhang, it’s also possible to build up enough speed to swing yourself up onto higher ground and a better tactical position. At this point in the series, however, it’s rare that you’ll have enough of a horizontal surface above your head to use the rope to its full potential. It’s something to be kept in mind, however, as following games give more and more reasons to use it against your enemies. As it stands here and in the future, care must be taken – the rope requires far more manual dexterity than almost anything else in the game, and using it poorly is likely to fling your worm into a watery end.

Attach the rope here…

And you just might be able to swing your way here.

Whatever damage you land upon friendly and enemy worms alike is subtracted from a worm’s typical pool of a hundred hit points. Once a worm runs out, they’ll pull out a plunger, announce their exit, and detonate themselves, causing a small amount of damage to the landscape and any nearby worms. Friendly fire is always in effect, which means that explosions of this and any other kind can damage and take out other worms, leading to potential chain reactions for teams grouped too close together. Incredibly satisfying when it happens to your enemies, much less so when your worm is the one caught in the crossfire. Explosions and certain other weapons will also send worms flying in various directions, quite possibly dragging more worms in their path with them into an even worse situation.

One explosion plus slippery ground makes for a very exciting first turn.

The environment itself can be just as much of a hazard as the enemy team, as well. Long falls will end your turn, potentially ruining a well crafted plan. Even more deadly is the rolling ocean that waits just underneath the map – should the landscape take enough damage that a worm could fall in, that’s the end for them. While landscapes often feature small islands where water spells danger, the more damage the landscape takes, the easier it is to get dunked. The sides of the map are just as deadly, meaning that one well placed explosion or Shoryuken alike can take out even the healthiest of enemies.

Finally, there are the land mines scattered all across the maps. Their small size and dark colors means they often blend in easily with the landscape, which makes it all too easy to tread over one and get blown away with no warning. Truthfully, these are probably the most annoying element of the game, since by default, they’re so common that it’s nearly impossible that you won’t inch onto at least one and end up wasting valuable turns and health. At the very least, they serve a strategic use in that they can be pushed around with explosive weaponry, potentially putting them in the path of your foes.

See that green landmine next to the crosshair? If you don’t, you’re going to wish you did.

All these concepts take some time to get used to, to be sure. The game offers no tutorial, which means that without the manual, you’re left to figure out the particulars of your movement and weaponry on your own. Once you get those figured out, however, the game becomes far more approachable. It’s about where then the game’s charms start to become more apparent, as well as the depth of strategies on offer. While there’s room for polish, almost all the elements that make the series what it became are here – simple and clear rules, a wide variety of different tools to work with, and gameplay that constantly straddles the line between strategic and chaotic.

Take the idea of the landscape that wears away as the battle rages. Solid ground gives way to danger, cover advantages wear away, and hanging chunks of debris have the habit of denying what could have been the perfect shot. In the destruction lay new opportunities, however, tunnels made, safe places to dig in brought into existence. In fact, a valid strategy is to take this to its logical extent – “dark side” play, as the manual calls it. Here, the strategy is to dig your worms into the dirt as tight as possible, block off possible entry points, and stay on the defensive. It’s not the most exciting method of achieving victory, but it’s as valid as any other.

Part of the real draw, however, is that perfect line it rides between goofy party fun and a real strategic exercise, never quite wholly becoming one or the other. There’s certainly arguments to made either way – the cartoony aesthetic, the way the wind can knock your projectiles off your intended path, and the random crates that can give the underdog a sudden advantage. The more teams in play, the crazier things get, and the bigger the blunders, sudden reversals, and strong reactions become. There’s no denying, however, that the player who uses their weapons wisely, calculates their aim just right, and knows every trick will certainly have the advantage. Perhaps a comparison could be made with Nintendo’s Smash Brothers series – approachable for those looking for wacky fun, but with more to offer to anybody putting in the time.

There’s also a small amount of customization offered to the game rules, should you be looking to encourage or discourage certain strategies. Turn clocks can be shorted, as can the game clock before sudden death occurs and all worms are brought to a single hit point. Weapons can also be given a certain number of shots or disabled entirely, should you find yourself sick of that guy who bundles himself up under three girders at once where you can’t touch him. On the cosmetic end, new teams can be created, with each of its worms being able to be renamed. Part of the fun of Worms is naming your team after friends, family, or your favorite game characters, and rooting for them to achieve victory.

At its time of release, most contemporary reviews of the time considered the game an instant classic, often raving about just how much time they had spent in multiplayer matches. Nowadays, given more than two decades of improvements, the original game comes off somewhat quaint. The biggest complaint to a modern player would likely be how light on content the game is. There’s no campaign mode, and not much on offer for a single player aside from testing themselves against the AI. While the computer s far from terrible, there are points when they’re capable of making shots that would seem impossible for a human. True Worms enjoyment, as a series mainstay, is best found with other warm blooded players.

Graphically, the many comparisons older reviews made between this title and Lemmings aren’t undeserved, with their tiny character sprites and static landmasses. Despite their size, however, the worms have plenty of charm to them, with each of their animations adding to the game’s goofy humor. Worms who fall too far will embed themselves into the dirt head first, example, while opponents who toss grenades with by flicking them up with their lower half, before headbutting them forward. The landmasses themselves also well designed artistically, with enough variety between tilesets to help keep the randomly generated levels fresh a while longer.

The game offers no music, which makes things sound somewhat barren. The silence is broken up with the sounds of gunshots, explosions, and most notably, the worms themselves. Each worm speaks in a high-pitched, somewhat posh British accent, or if you’d prefer, equally squeaky French and German. Whatever language you prefer, worms will call out friendly fire, compliment themselves on good shots, and promise revenge on their attackers, among a good deal of other clips. It’s a small touch, but the game, let alone the series would be poorer for its loss, listening to the worms complain and celebrate just as their players do.

There’s an assortment of smaller touches that help polish the experience as well. An automatic replay starts up at the end of an especially exciting turn, great for watching your triumphs and mistakes alike unfold once more before your eyes. Colored bars seemingly stolen straight from Street Fighter II give a quick readout of a team’s overall health, while a scrolling ticker gives out silly, worm related slogans at the start of a round. In a nice touch, some environments offer gameplay tweaks as well – fight on Mars, and you’ll have worms with higher jumps, for example.

With how well the original game did, even on the constraints of dying hardware like the Amiga, it was no surprise that ports would follow. While the quality of the game’s ports themselves have their highs and lows, a majority of them have extra polish and features not offered in the original version.

The CD32 version looks and plays identically to the disk version. Thankfully, scrolling around the map for a better view is as simple as holding down a button and moving the D-Pad, so the lack of a mouse doesn’t particularly get in the way. The biggest addition is the introduction of a CD soundtrack, including the first appearance of “Wormsong”, a heroic military march sounding theme that’d make several more appearances throughout the series. The rest of the soundtrack is far on the atmospheric side, featuring effects like blowing wind, demonic laughter, and buzzing insects, only mixed occasionally with occasional stings of music. It gives the game a surprisingly creepy, desolate feel, and while it mixes well with the more strategic, thoughtful nature of the game, It clashes somewhat with the cartoony aesthetic. There’s also a handful of 3D rendered cutscenes that play as the game starts, depicting the worms engaging in all manner of weapon-related cartoon violence.

The Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis versions only saw release in Europe, and neither of them are especially good. The physics have been altered that everything just feels ever so subtly off, with the changes leading to the removal of the ninja rope. These ports also don’t randomly generate maps, instead pulling from about twenty pre-made maps. Most of the different environment types are missing as well, with nearly all the voice clips going along with them. Finally, while moving and aiming isn’t so bad on a controller, having to scroll the screen with the D-Pad generally takes up too much of your valuable turn time compared to simply using the mouse. These ports are functional as games, but you certainly wouldn’t be getting an accurate representation of the game through them.

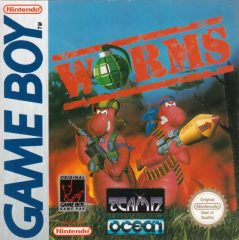

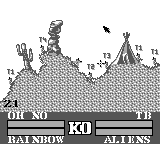

Much like the 16-bit versions, only Europe saw Worms on the Game Boy. The fact that it could handle Worms in any form is perhaps due some applause, although this port pays a high price for it. The weapon set has been further trimmed, losing the blow torch and drill along with the ninja rope. The physics are even further askew from the other 16-bit ports, with floaty jumps, explosions that seems to reach a little too far, and a number of other oddities that start to stick out the more you play it. Perhaps the most impressive thing this particular port can claim is that it can still support all sixteen worms on the battlefield at once. Unfortunately, given the bare bones nature of this version, it only serves as a technical curiosity, more than anything.

The DOS version adds an assortment of minor gameplay and visual tweaks, offering something even beyond what the Amiga version had on offer. It includes the CD soundtrack of the CD32, as well as higher resolution versions of its FMV cutscenes. Visually, there’s a new scaling effect where the camera zooms in and out to focus on the worm currently in play, some extra landscape types to battle on, and a far wider color pallet than the Amiga’s somewhat muddy color section. A number of new gameplay options are available, from minor adjustments like being able to see the time left in a round, to “Banzai Mode”, where explosions are made far more deadly, to toggling the sudden death period that occurs when time’s up. Nicest of all, however, is the ability to enter in a seed to generate a map with, should you end up find a particular favorite among the 4 billion or so. The gameplay itself is unaltered otherwise, making what stands as the gold standard of ports.

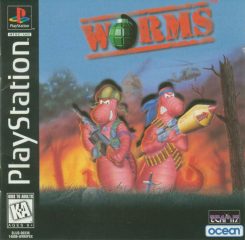

The PlayStation and Saturn ports are nearly identical to the DOS version, aside from controllers. Since scrolling is a simple as holding down a button, however, it makes for a very slight adjustment period. The Jaguar version uses both as a base, but loses the scaling, FMVs, the replay mode, and some of the voice clips. It also attempts to recreate the CD version’s soundtrack in .mod format, something none of the other ports attempt. All are solid ports, and serve nicely if a console would be your preference.

Screenshot Comparisons

Amiga

Super Nintendo/Sega Genesis

PS1/Saturn/Jaguar/DOS

Game Boy