Sakura Taisen is the quintessence of the Japanese cult-hit video game franchise. It began with a poetic vision cultivated by a dream team of accomplished creators, it survived tribulations as it took double its scheduled development time, and then it sold out within hours of its release. From there, it spawned stacks upon stacks of sequels and side games, anime series, manga, albums, and books. As if the mountains of media were not enough, Sakura Taisen musical stage shows went on regularly from July 1997 to August 2006, and a dedicated Sakura Taisen shop and cafe in Ikebukuro operated daily from June 1998 to March 2008. This is no ordinary game franchise, and its devotees are no ordinary fans. Despite the admiration and dedication it’s earned in Japan, though, it remains largely unknown elsewhere.

On the surface, Sakura Taisen is a series of hybrid bishoujo visual novel and tactical mecha combat games, set in alternate-history 1920s Tokyo, Paris, and New York, with masterpiece-level writing, voice acting, art, and music. It follows several troupes of (nearly) all-female robot pilots who fight against demons and evil magic, all the while working undercover as musical theater performers. Its worldview embraces absurdity, sentimentality, and nostalgia. Its prime mover, its raison d’être, and its pride and joy have always been its characters. Its unapologetic Japanese-ness has made it simultaneously aloof and exotically fascinating to audiences outside of that country. If any of this sounds intriguing to you, please come along…for Taishou cherry blossoms and a storm of romance!

The story starts in 1994, with a phone call from Shouichirou Irimajiri, VP at Sega, to Ohji Hiroi, a well-regarded writer and producer and the founder of game developer Red Company. Irimajiri wanted to fill the adventure game gap in Sega’s first-party lineup, and thought Hiroi and Red Company had the sort of creative talents needed for such a project. Hiroi agreed, and the two started collaborating at a furious pace, building up a mountain of ideas. They dreamed up characters, then imagined scenes for them. Upon seeing a tabletop war game being played in the office, they decided to add tactical combat to their adventure concept.

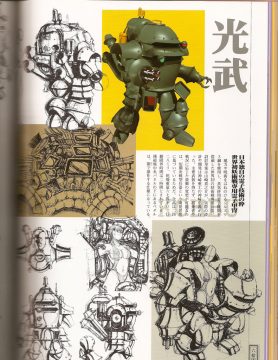

Early on, they recruited legendary comic artist Kousuke Fujishima (of Oh My Goddess! fame) to lend his sentimental style to the character designs, and famous anime composer Kouhei Tanaka (Gunbuster) to provide an especially impassioned score. Fujishima brought aboard animator Hidenori Matsubara to help with the massive amount of in-game art and animated sequences. Futoshi Nagata provided the iconic, retro-futuristic mecha designs.

Continuing the all-star recruiting, writer Satoru Akahori (Sorcerer Hunters) was brought on board to start on the scripts. Because Akahori felt most comfortable writing anime scripts, he simply wrote in an episodic format, to the degree that at the end of each episode there was a preview of the next one. Development took double the planned amount of time, and the game wasn’t released until September of 1996. What had at times seemed like a hugely over-ambitious project ended up being a huge hit, selling out on the morning of its release.

Sakura Taisen takes place in a romanticized alternate-history version of 1920s Tokyo (and later, other cities of the world). On the imperial-era-based Japanese calendar, the Taishou Era roughly corresponds to the time between the two world wars; Sakura Taisen makes frequent reference to its era, but uses slightly different kanji to indicate its divergence from actual history. After World War I, Japan enjoyed increasing importance and recognition in international affairs. Its urban citizens became more prosperous, cultured, modern, socially-aware, and cosmopolitan. This optimistic, romantic “Taishou Democracy”, to Hiroi, represents the starting point for an ideal future for Japan. He wished to rewind to that moment in history before the loss of innocence in the tragedies of WWII, to a time when Japan was an eminent member of the world community on its own terms, just as much as America and the European cultures. Especially in the “teito”, its bustling Imperial capital.

Everything in Sakura Taisen is infused with that Taishou-era flair. Text in the scene is written right to left, as was the custom of the day. The game manuals are printed with their spines on the right, as left-spined books didn’t come into vogue until later decades. All numbers, even when they would normally be written with the more modern Arabic numerals, are written in kanji. This overall aesthetic pervades the design, typography, music, and even the little steam-powered onscreen UI elements.

Nothing says Taishou Democracy like a Western-style musical theater interpreted with a Japanese sensibility. The Teikoku Kagekidan (“Imperial Revue”) is the musical theater troupe that serves as the main characters’ cover while they are pursuing secret military missions. It is very heavily inspired by the Takarazuka Revue, a real-life theater troupe that has been performing in Kansai for the past century. Both put on spectacular, Broadway-style musical theater. Both are also all-female, with some women specializing in male roles. Further, they’re both also divided into sub-troupes, including a hanagumi, (“flower troupe”); this is the division the main characters belong to. That flower theme pervades the series, with all of the main characters being named after flowers, floral imagery appearing in most graphic designs, and so on. Even the series title translates to “Cherry-Blossom Wars”.

The mostly-authentic Taishou Era setting is just the beginning, though. Added to this are absurdly advanced steam-powered machinery and reiryoku (“spiritual power”). This is the “alternate” part of the alternate history setting. The steam-powered technology in Sakura Taisen is already in some ways more advanced than modern electronics in the real world; adding the supernatural gets you combat robots that could hold their own in any mecha anime. The main purpose of these robots is to fight off demons who are attempting to invade the human world.

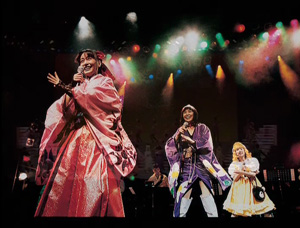

Securing a top-notch voice acting cast was crucial to the Sakura Taisen project. Because music and stage performance are central to its theme, Hiroi Ohji scouted many of the cast members by going to live music performances and looking for women who could really sing, rather than just going through voice-acting agencies. He also sought out people who could “speak as if they were singing”; that is, people who had a lyrical quality to their voices even when talking normally.

The importance placed on the voice acting is evidenced by the precise synchronization of the onscreen portraits’ mouth movements with the actual phonemes being spoken – this is something still not done in many games today, and frankly it’s mysterious how they did it in 1996. (Sometimes I imagine some poor intern, doomed to program the timing of every mouth-flap for every syllable of voice recording throughout every ST game.) Another testament to the voice acting talent is the way that the voice-acting cast became just as idolized by fans as the characters were, and were even conflated with the characters in the live stage shows.

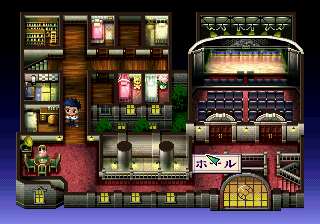

The Sakura Taisen games unfold like an anime series, each divided into about 10 episodes. An episode typically starts with some day-to-day situation in the theater, presented in a cutscene style that should be largely familiar to anyone who has played a JRPG or visual novel. The daytime scenes are generally a way to get to know the theater cast as a group, the way they behave professionally and as friends. Next comes an eyecatch, just like when a televised anime is going to or coming back from commercials. This serves as a milestone in the chapter, and gives the player a chance to save.

At night, the player is given some time to roam around and talk to specific characters. These evening rounds are limited in time, so you only get to see a couple out of all the possible scenes on a given night. The night scenes give you a chance to see the more personal side of each character; this is when secrets are confided and promises are made.

After the night rounds, some sort of crisis is guaranteed to occur and the squadron is ordered to sortie. You get another eyecatch, for a chance to save your game and check your squad members’ yaruki (“motivation”). This statistic is based on how satisfactorily the player has been handling Ohgami’s interactions with the squad members. Now you get to see yet another side of your troupe, under pressure and in the heat of battle.

In the first two games, battles occur in a tactical robot combat simulation system, plus, at times you are also expected to have meaningful exchanges with your squad on the battlefield. Sakura Taisen 3 debuts a new system with its own contrived acronym, ARMS (“Active and Real-time Machine System.)

After the battle is a concluding victory scene, including the absolutely essential victory pose. All of the characters that played some part in the battle gather together and call out in unison, “Shouri no po-zu…Kime!”, (“Victory pose… Go!”) The resulting group shot serves as a celebratory image for the episode, and reinforces just how character-focused these games are.

Following the victory pose is the preview of the next episode. Yes, each episode has a short clip of scenes from the next episode, with a voiceover exhorting you to tune in! When Akahori said he was most comfortable writing for anime, he meant it. The voiceover is provided by one of the characters, and ends with the catch phrase “Taishouzakura ni roman no arashi!” (“Taishou cherry blossoms and a storm of romance!”) “Roman”, meaning “romance”, is yet another key concept in Sakura Taisen. Here it refers to the philosophical meaning of romance – while the series is about love, in Japanese it mainly means an optimistic, idealized view of the world, which Sakura Taisen exhibits proudly.

This pattern repeats, chapter after chapter, game after game. Gradually getting to know the characters around you, from all of these different angles, and coming to care about them over the course of dozens of hours, is the core of Sakura Taisen‘s appeal.

Sakura Taisen officially calls these more mundane scenes the “adventure” portion of the game, because of the random and nearly meaningless nature of Japanese game genre naming. The bishoujo (“pretty-girl”) game subgenre, focusing on interactions with charismatic female characters, originated in the 1980s as a niche largely comprised of pornographic PC titles. For the most part, it happened to make use of the text- and-still-image-based template of the “adventure” genre. The breakthrough of bishoujo games into the mainstream was Konami’s 1994 title Tokimeki Memorial. It pioneered the dating simulation subgenre, which focuses on time and stat management, and proved that bishoujo games (or “gal games”) could appeal to a wide audience, and could be clean and wholesome. It demonstrated that there was a market for games focused on relationship cultivation, even without the erotic hook.

Sakura Taisen was part of the barrage of console bishoujo games that followed in Tokimeki Memorial’s wake. Most were straightforward interpretations of the same contemporary high-school dating theme, with NEC Interchannel’s 1998 title Sentimental Graffiti being the most successful. Sakura Taisen, however, fused the bishoujo and dating sim tradition with a melange of other concepts: tactical RPG combat, a retro-futuristic setting, and a dramatic, musical theme. Sakura Taisen always reinvents everything that it borrows, too, so of course it implements its own unique dating-sim system: LIPS.

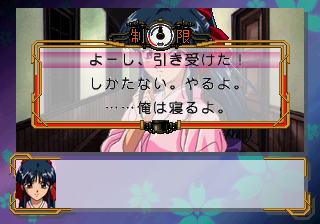

LIPS stands for “Live & Interactive Picture System”. It includes several types of interactions between the protagonist and the rest of the cast. The most basic of these is the typical visual novel multiple-choice question, in which the player is asked to decide what to say or do next. Most of these decisions are accompanied by a countdown timer; if you don’t make a choice in time, your character will either keep quiet or blurt something inevitably worse than any of the offered choices. This adds tension beyond the ordinary VN decision points.

Another basic LIPS scenario is a bust portrait view of a character in which you are given control of a cursor. You can move the cursor around the screen to interact with the character in various ways. Hover over their eyes, hair, clothes, possessions, and so on to turn the cursor into an eye, and press the button to look. Sometimes this yields an internal monologue from the protagonist on the qualities of the clicked feature; sometimes it starts a brief conversation, and other times it elicits a “quit staring at me” from your interlocutor. Hover over the mouth for a talk icon, and push to continue the conversation.

Depending on your answers and actions, you may positively or negatively affect your relationship with the characters present; these changes are indicated by a rising, major-scale jingle and a falling, minor-scale jingle, respectively. Throughout the series, Sakura Taisen masterfully trains the player to have a Pavlovian reaction to these positive and negative reinforcements – every good jingle is a victory, every bad jingle a tragedy. A bad jingle with your favorite heroine? Utmost shame. Occasionally, you have no choice but to harm your relationship with one character in order to better your standing with another. Other times, you may have the opportunity to improve the trust level of all of your teammates at once. During the adventure part, though, your trust level with each heroine is kept secret; you need to wait until the eyecatch to check on their motivation levels. Because the trust your squad members have for you directly affects their motivation in battle, your understanding, kindness, and values in the LIPS parts are crucial to succeeding in the combat parts.

The adventure sections form the heart of the series, unfolding at a deliberate pace, gradually building up the player’s willingness to identify with the protagonist, and likewise deepening the protagonist’s relationship with the rest of the Teikoku Kagekidan. Naturally, at a crucial point in the story of each game, you will be prompted to choose a heroine to pursue a special relationship with – the nature of this romance is chaste but very meaningful, and can be developed over the course of several games.

The idea of intertwining visual novel/bishoujo game conventions with traditional combat systems made its way into other titles. In the 1990s, this included RPGs like Thousand Arms and Langrisser III, where the protagonist’s romantic relationship with one of several female cast members affected the storyline. Atlus’ Persona series adopted a relationship system in its popular third and fourth installments, with deeper connections leading to more powerful summons in combat. Sega’s own Valkyria Chronicles is the most Sakura Taisen-influenced game of all.

When Sakura Taisen was conceived, tactical RPGs had a long tradition on consoles going back to the 8- and 16-bit eras: notably, Nintendo & Intelligent Systems’ Fire Emblem series, Koei’s Nobunaga’s Ambition series, Masaya’s Langrisser series, and Sega’s own Shining series (just to name a few). As mentioned previously, though, the tactical combat system in Sakura Taisen was supposedly inspired not by video games, but instead by tabletop war games.

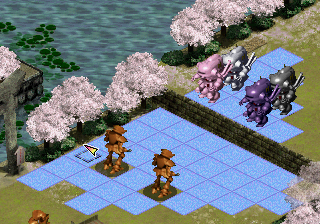

Battles are fought with Koubu (“warrior of light”), steam- and spiritually-powered robots manufactured by Kanzaki Industries. Each character has a Koubu of a distinctive color, with a unique weapon. The squad members pilot their Koubu against robotic and demonic threats in turn-based combat; in the first two Sakura Taisen games this happens on an isometric grid similar to Front Mission.

The original combat system allows each unit to perform two actions per turn, from a menu with options such as Attack, Defend, Move, Deathblow, Charge, and Heal. Each unit has an HP gauge and a “kiai” (“fighting spirit” gauge. When moving, the eligible destination squares are highlighted in blue. When attacking, the shape of the character’s attack area is highlighted in pink – making use of the shapes of attacks possessed by your characters is a key part of mastering the battle system.

Ohgami and Sakura’s katanas can only reach one square in any direction, Sumire’s naginata can attack two squares away, Maria’s guns can fire several squares away in four directions, and so on. The kiai gauge can be spent to perform deathblows, attacks that invoke a full-screen animation effect and deal lots of damage. When you have reached the moment of truth and chosen the heroine you like best, a gattai (“unity”) technique becomes available in which the two of you team up to deliver an especially dramatic and powerful attack.

Upon completion of the game, each Sakura Taisen game offers a new mode, called Teito no Nagai Ichinichi (“A Long Day in the Capital”). In this mode you roam around the theater, which has bonus activities located in various areas. You can see any of the movies or still event images you have unlocked, listen to music, play minigames, and so on. As the series goes on, these bonus materials get more elaborate, to the point that you can almost spend as much time with the post-game experience as you did with the game itself.