- Myst (Introduction)

- Myst

- Riven

- Myst III: Exile

- Myst IV: Revelation

- Myst V: End of Ages

Myst is an adventure game series created by Cyan. But you already know about Myst don’t you? Everybody has played Myst. You played it, your friend played it, your mom played it and your cat probably gave the mouse a few clicks while your back was turned. While Myst is one of the better known names in the video game industry, it is mostly because of the first game, as not as many people are familiar with the later entries.

There are actually six games in the Myst series, but only three of those are especially relevant, as they are all masterpieces in their own right and ended up defining Cyan as a company. Two Myst games were developed under license by other companies: Myst III was developed by Presto Studios (makers of The Journeyman Project) while Myst IV was developed by Ubisoft Montréal. For that reason, they feel a little bit… off. Myst V, while developed by Cyan, was a kind of “farewell gift” to longtime fans, made up of unused concepts meant for Uru.

This leaves us with three very important titles: the original Myst, its sequel Riven, and the tragically visionary MMO Uru. The original Myst is the game that started it all. Not only is the first Myst a perfect example of a small team creating a masterpiece and a runaway hit, but it also gave birth to an entire subgenre of adventure games. Riven was to be more of the same, but bigger and better in a multi-million dollar adventure game spanning five CDs. Uru, on the other hand, was born out of the hubristic proposition that you could create a Massively Multiplayer Online Adventure Game. This, as recent history has shown, was not the winning idea that Cyan thought it would be. Uru is the focal point of the Myst franchise, not necessarily because it is the best game, but because it was a gigantic project, one that represented everything the people at Cyan always wanted to do. Not only that, but Uru, in all its doomed grandeur, almost singlehandedly bankrupted the company… which has never quite been the same since.

At its core, the Myst franchise is about fulfilling a fantasy of loneliness – you’re all alone in surreal imaginary worlds without anybody to kill you or bother you and plenty of puzzles to keep your mind occupied. As you start each game, the story’s most important events have already occurred and it’s up to you to piece together what happened from journals, drawings and various objects in the rooms. Everything has an “after the fact” feel. The series is also a noble representative of the “figure-out-what-the-hell-you’re-supposed-to-do-if-you-can” school of game design. You could call those puzzles “non-directive tasks”, but that sounds a bit like psychology babble. In other words, you are thrown in a mysterious world without knowing what you’re supposed to do, where you’re supposed do to it, how you’re supposed to do it or why. One has to admit that a game that relies on this type of task isn’t exactly attractive or easy to get into, but when you make the extra effort, the payoff is really incredible.

The games’ manuals are a perfect example of this design ideology – outside of an introductory letter from some character and basic technical information, you are provided no character bios, no historical background, no gameplay help and no tips. Figuring any of this out is going to be your job. So even saying what a puzzle is about in a Myst game is already giving away half of the solution. Even providing vague hints about the story or the overarching goal is already shedding some light on what should be total darkness.

In presentation as well as interface, Myst is known for its minimalism. That hand floating on the screen, that’s you. You click on stuff. That’s it. There are no dialogue trees and no item lists. Myst is also notorious for having weird machines and crazy locks standing right in front of every single worthwhile destination. Any claim that Myst is full of intuitively placed puzzles that reward everyday logic is frankly indefensible. You either have to accept this or cut your losses and start running right now. On the other hand, most people only remember the first game, so they don’t know about the effort that was put in later games to better integrate the puzzles in the environment. Riven is particularly successful in that regard.

Still, there are recurring themes in Myst puzzles. Here are the three golden rules:

The first is: Machines won’t work if you don’t restore power. Do that first. Water, wind, sunlight, breakers, electric current… that weird machine won’t do a thing without juice.

The second is: If a symbol looks important, it is. Write it down. Yes, with a paper and a pencil. The pointy thing and the rectangular thing. Yes, you probably bought a computer to get away from those. It doesn’t matter. You should also note the initial position of complex machines because a) it might already be set in a favorable position and b) you might click yourself into a corner by messing around without knowing what you did.

And the third is: The more inaccessible the back of an object is, the more likely it is that there’s going to be something important there (the path of most resistance is always the right one, obviously). So look behind doors and under elevators. If an area can reached in two different ways, you can be sure something happens when one entrance is closed and you go through the other.

Although this wasn’t fully thought out as of the first game, Myst is about a race called the D’ni. They are long-lived humans who built a city deep under the surface of our planet Earth and thus have a natural aversion to bright light. What is truly interesting about them is the Art, the ability to write worlds called ages and “link” to them using special books. You put your palm on a book created for this purpose and presto, you’re in a new world! This is an obvious but fitting metaphor about the power of books, computer programming and the written word in general. The interesting tidbit is that this age isn’t created by the writer: it is merely “linked to” from an ocean of infinite possibilities. Every age is unique – you could write exactly the same words twice and not reach the same place again, only a very similar one. You can probably handle the philosophical implications on your own.

Rand Miller is the father of the franchise as well as a guru to the fans of the universe he’s created, making him a bit of a diminutive George Lucas. It also helps that he plays Atrus, the Myst series’ central character. Richard “RAWA” Watson is Cyan’s official D’ni “historian” and has also been a major influence in creating the D’ni mythology. As an amateur linguist, he created an entire language for the D’ni (both spoken and written) by drawing from his knowledge of Hebrew, German, Spanish, and of course English. The sign of a real Trekkie is that he speaks Klingon fluently. Accordingly, the sign of a hardcore Myst fan is that he can read and speak D’ni… and correct mistakes in the game’s script. The D’ni also have their own numeric system and are obviously quite obsessed by numbers and gizmos

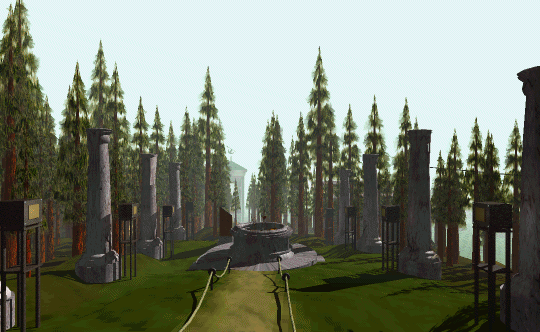

The creators also strived to give the D’ni their own architectural style. To make it seem more authentic, the in-house rule was to make everything as original as possible by not resorting to any sci-fi or fantasy cliché. The result is a mix of art nouveau, tribal design and monolithic stone structures that’s hard to compare with anything else. Over time, the franchise’s style became increasingly unique, but kept touches of steampunk, because the usefulness of elevators and wacky door mechanisms is undeniable no matter the historical setting.

The Myst games were made with a level of attention to detail that is almost unparalleled in videogamedom. Very few companies have an obsessive-compulsive attention to detail, especially when it comes to handling visual elements and ambient sound effects. Maybe there’s something about living in the primeval wilderness of the west coast that inspires game makers to create more interesting landscapes and appreciate the sound of the wind blowing through the leaves? Every Myst also has well-hidden Easter eggs, their existence often leaked by an “anonymous source” that gives the fans some extremely obtuse hints on how to find them. So even when you think it’s over, there’s still something else to look for.

And yet the critics lament: “Loneliness, puzzles and visuals are nice, but where’s the story?” Granted, Myst may be low on narrative, but it is really high in history. How many games strive to create their own architectural style and bother to invent a language, both written and spoken that fans can actually speak? Everything in Myst happens after the fact, but you can always find signs of past events and tie together what occurred.

There is a practice called letting the player “close the circle” when it comes to telling a story, meaning that the player has to put some of the pieces together to fully understand what is going on. This can be done by hiding storyline details or withholding them completely, instead of spoon-feeding the plot. The end result of this narrative practice is that the player builds a deeper relationship with the events, because they did some of the intellectual legwork. Remember how cool it was piecing the chronology of Pulp Fiction together? The other advantage is that if you don’t give a damn about stories, you can just focus on the task at hand, ignore all extraneous details and enjoy the ride. If you don’t want Myst to have a story, it doesn’t have one. No endless text, no incessant cutscenes, but an endless amount of little details to discover that add up to the hidden story of a civilization’s downfall.

Video games aren’t always particularly good at storytelling, but on the other hand they are excellent at worldbuilding. This is where the ages come in, obviously. Myst games aren’t about people, but places. The worlds, or ages, are the true characters of Myst. In fact, some people do not even consider Myst an adventure game, because it has little to no character interaction and puts heavy emphasis on visual and aural design. Perhaps it’s an artistic 3D virtual environment simulation with embedded logic problems, far removed from the inventory puzzles of the LucasArts/Sierra mold. Despite its initial popularity at the time of release, it was commonly criticized by core gamer magazines for being pretty but shallow, a complaint which holds water when the first game is viewed by itself, but falls apart due to the efforts of the later installments.

While many runaway hits in the video game world have now turned into colossal billion-dollar franchises, Myst somehow fell off the radar entirely. This is most likely because Cyan missed a crucial step in their development as a company, one you hear often about in management circles – going from a successful small business to a very successful large business. Obviously, you don’t always get the chance to take that step, as success can be fickle. Conversely, some companies choose not to grow larger, because the decision is not easy as it sounds – while you’ll be swimming in cash, you’ll lose creative control over your baby and see it turn into a soulless monster that hungers for more money. It’s actually a tough choice, one that Cyan didn’t or couldn’t make. Myst was their baby after all, one they weren’t going to turn into a complacent cash cow. The Sims has since become the best-selling game of all time, supplanting Myst.