Full Motion Video Games; loved by few, scorned by most. Often considered a blight upon the early era of CD-ROM games, and sometimes even blamed for the death of early consoles using the technology (Sega CD, anyone?), the truth is that while they are in most cases pretty forgettable, there is a reason that so many were made: people were excited by them at first. After the start of the infamous hearings on video game violence in the mid-1990s, Night Trap, one of the flagship FMV games for the Sega CD, became a huge best-seller, and many other games were released in the wake of it. Once the novelty wore off though, people saw how boring and repetitive most of them were.

The truth is that FMV games actually got their start almost a decade earlier. In an intriguing example of history repeating itself, the first FMV game to take the world by storm was actually released in 1983, before most people even considered putting anything but music on a CD. Instead, all of the video was placed on a laserdisc, which was, for all intents and purposes, the forerunner of the DVD. The laserdisc player housing the disc was placed inside an arcade cabinet, and with ROM chips controlling what parts of the video were played when, you had the first FMV games. While not the first game in this format (the first was Quarter Horse, a horserace betting simulator released in 1982, and Sega’s Astron Belt was released in Japan earlier in ‘83), Dragon’s Lair is considered a classic and the first major success of the genre, and inspired a glut of little remembered imitators, very similar to the FMV games of the early CD-ROM era. In fact, it was due to this brief revival of the genre that several classic laserdisc arcade games were re-released. However, many were not, and there is usually a direct connection between the games that were re-released on later formats to the ones that are still remembered today. Dragon’s Lair and its follow-ups, having been kept in the public eye thanks to numerous ports, sequels, and conversions, are some of the few games of this type to be remembered to this day outside of hardcore fans.

Dragon’s Lair was released in the middle of the great video game crash of 1983. Home consoles were on their knees, and arcades weren’t doing much better. According to contemporary news coverage, many analysts were estimating that somewhere between twenty-five to fifty percent of all arcades would close by the end of the year. Things looked quite grim.

Upon release, it’s hard to overestimate how jaw-dropping it must’ve been for gamers used to staring at small, pixelated sprite characters to see a game where all the action is presented through a well-animated cartoon. Many arcades hooked up a second monitor above the cabinet so people could watch the game being played while waiting in line. Even though the game cost fifty cents, double what most arcade games cost at the time, everyone wanted to experience this unique game. There is a news clip about the game which has a section dedicated to asking a few players about what they think of the game. One gamer calls it the best game he’s ever played. Another tells the reporter that he spent at least forty dollars before beating it for the first time. There were numerous ports, tons of merchandise, and even a short-lived Saturday-morning cartoon. Dragon’s Lair was a phenomenon.

The game was the brainchild of Rick Dyer, who had based the concept on a failed attempt at marketing what he called the Fantasy Machine. Inspired by early text adventures, the Fantasy Machine was similar to a “Choose Your Own Adventure” book. Early versions had a scrolling paper reel with prose narrative and illustrations that would scroll to the proper scene based on decisions made by the player by pressing buttons corresponding to different actions. A later revision used a laserdisc with still images and voiced narration. Due to the failure to sell it to a manufacturer, only one game was designed for it, The Secrets of the Lost Woods.

Dyer concluded that the main issue with the Fantasy Machine was that it wasn’t thrilling enough for kids who had come to expect constant action and excitement in their entertainment. Trying to figure out a way to make his concept marketable, inspiration struck when watching a recent animated film called The Secret of NIMH. Dyer decided that an exciting action-based script, brought to life through high-quality animation, was what his project needed.

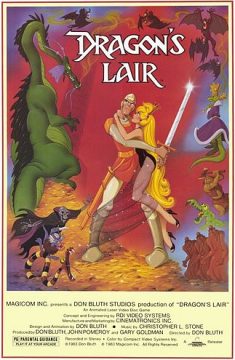

Rick Dyer decided to go to the source of the movie that inspired him, Don Bluth, an ex-Disney animator who had struck out on his own after working on several Disney projects such as Robin Hood. Bluth agreed to work with Dyer, and, along with Bluth’s producers, Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy, their team produced approximately twenty minutes of animation for the game at a cost of one million dollars. With most of the budget going to Bluth’s lavish animation, there was little funding to hire professional voice actors. Only one professional voice talent was hired, Michael Rye, who played the narrator delivering the memorable attract mode speech. Other characters were portrayed by Bluth’s staff. Dirk the Daring, the protagonist, was played by the film editor, Dan Molina. Vera Lanpher, the head of animation clean-up, played Princess Daphne.

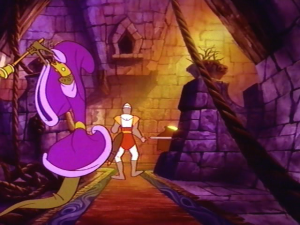

The story is simple, but well presented. You play as Dirk the Daring, a valiant but bumbling knight who attempts to storm the castle of an evil wizard (who doesn’t appear in person until a later game) and save Princess Daphne from a dragon (later named Singe). Nothing new to gaming, much less storytelling in general, but the presentation was unlike anything gamers had seen before. Even before starting the game, the player is treated to an attract mode that gorgeously sets the stage, with character introductions, tons of action, and unusually memorable narration.

Characters

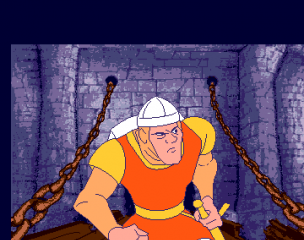

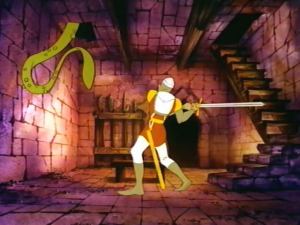

Dirk the Daring

The hero of the story, Dirk is a brave but slightly inept knight who wishes to save the princess, Daphne, from her imprisonment in the castle of the evil wizard Mordroc. He doesn’t talk much, but he means well, and if the player knows what they’re doing, can be competent enough to fumble his way to victory.

The concept of Dirk’s character evolved during the production. Bluth felt that Dirk should not behave like a typical hero, and instead be more of a relatable “everyman”. Due to this, Bluth struggled writing lines for the character. It was felt that whenever he tried to write dialogue for Dirk, he started to sound more like a competent hero. It was eventually decided that Dirk should have minimal dialogue and be portrayed mostly through his reactions to situations. Dirk only speaks two actual lines in the final game, both being one-word exclamations.

Princess Daphne

Dirk’s objective and potential love interest, Daphne has been imprisoned in a magical glass globe and is guarded by Singe the Dragon. She doesn’t do much other than give Dirk some advice and look pretty during the game’s climax. Her design was based off a combination of Marilyn Monroe and numerous Playboy centerfolds.

Singe the Dragon

The guard of Daphne’s prison, Singe dwells in the titular Dragon’s Lair at the bottom of the caverns below the castle. He has the key to Daphne’s prison around his neck, and you’ll have to kill him to get it.

Mordroc

The evil wizard who owns the castle Dirk is exploring. He doesn’t appear in person or get referenced by name until Dragon’s Lair 2, but once he does, he’ll cause Dirk a lot of problems.

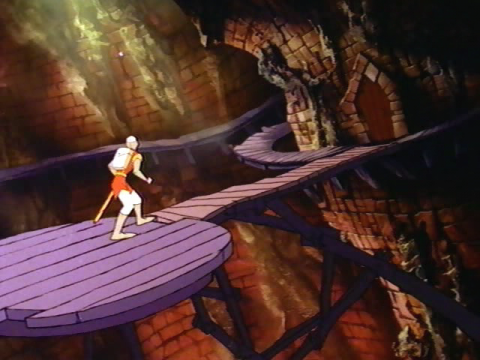

The gameplay consisted of watching the video as Dirk made his way through the castle and caverns below, and when he was in danger, the player was expected to either move the joystick to guide Dirk’s movements or press the button to have him attack with his sword. If the player made the “right” decision, the game would continue, otherwise, the game would switch to a scene of Dirk being dispatched by one of the many, many hazards of the castle. Simply put, the game is a glorified series of Quick Time Events.

Exciting at first, and somewhat enjoyable if you know what to expect, but the hazards often come so quickly that you rarely have more than a split-second to react, and so first-time players are bound to be frustrated, especially if playing the original Arcade version, which requires much more exact timing in comparison to later home versions, where it feels like the move requirements were greatly simplified.

Memorization is mandatory, requiring lots of trial and error, and except for a few instances where certain objects and parts of the room will flash to signify different options, there are no direct hints to clue the player in on the proper solution. Once the whole game is committed to memory, there’s really no reason to play it again except for the animation. For this very reason, many recent ports have allowed the player/viewer to simply sit back and watch all the scenes play out like an animated short, or even play the game with move prompts to let you know what to do when.

Even so, the animation is so breathtaking and the scenarios creative enough that there is enjoyment to be had if you accept the limitations. Here are just a few of the more memorable set-pieces:

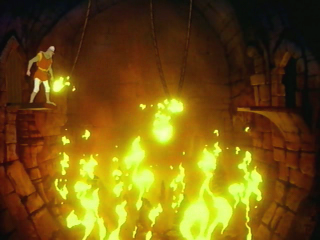

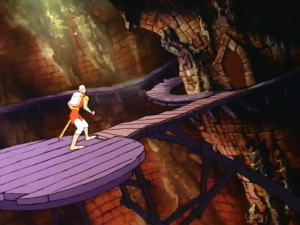

Fire Pit

Likely the first room you will encounter on your journey, the Fire Pit sets the stage nicely as Dirk is forced to cross a flaming chasm on a series of swinging ropes that are also on fire.

Flying Barding

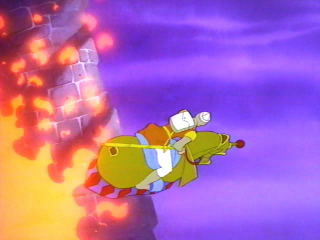

Dirk makes the mistake of climbing on what appears to be armor for a horse and gets taken for the ride of his life. A very tense and dynamically animated scene.

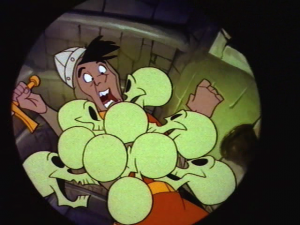

Pirates of the Caribbean

Dirk takes a wild raft ride through treacherous waters. The foreboding signposts add a good measure of uneasy humor to the proceedings.

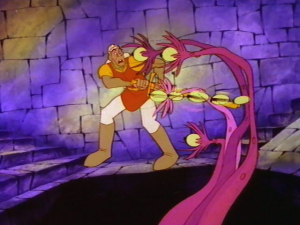

Pot of Gold

Featuring one of the more memorable and dangerous enemies you will face, the Lizard King will definitely give Dirk a run for his money.

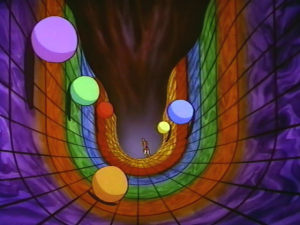

Yellow Brick Road

Dirk must dodge through a gauntlet of traps, snakes, and giant spiders. Supposedly, the death scene with the flying knives is slightly censored from prototype versions.

Chapel

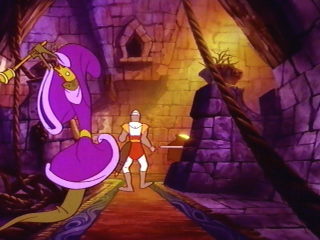

Dirk is halted by a mysterious opponent who can electrify the floor. Dirk must watch his surroundings carefully to make his move.

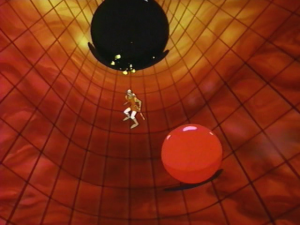

Dragon’s Lair

Time for the main event! Dirk’s wits and skill are put to the test as he faces off against Singe the Dragon in order to save Princess Daphne.

One strange feature of the game is the fact that many of the levels have two versions, both exactly the same except for the animation and moves you must make being mirrored. This would be fine if it weren’t for the fact that instead of the game just randomly picking a version each time you play, you actually have to play both versions on a single playthrough. It feels very lazy and is nothing more than an obvious attempt to pad out the game.

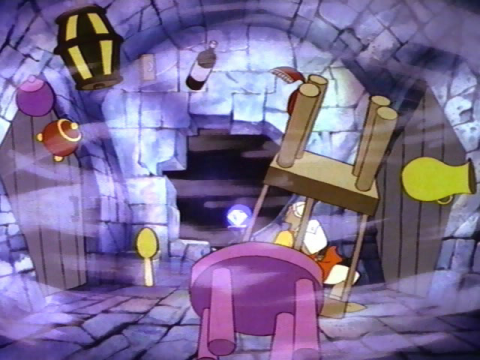

Screenshots from prototype footage

Early prototypes of the game had a much more free-form gameplay style, allowing for multiple paths through many of the game’s scenes. This is quite different from the final version, which was much more scripted, introducing the memorization aspect that FMV games would become known for. A few scenes were cut completely. Some evidence of the differences remained in the final version though, especially in the backgrounds of the Game Over scenes of Dirk becoming a crumbling skeleton, which often still have the alternate pathways out of rooms left in. Many of these “deleted scenes” were either recovered or even recreated from scratch for the 20th Anniversary Edition and are completely playable for a unique look at what an alternate version of the game might have been like.

Screenshots of unused footage restored for the “Home” version

One strange omission from the arcade version is the fact that the opening scene was almost completely cut from the game, even though the footage is still on the laserdisc. In the arcade version, the game opens with an establishing shot of the castle where the game takes place, cuts to Dirk charging inside, and then the game cuts to a different scene. The game was originally supposed to start with a scene taking place on the castle drawbridge, portraying Dirk’s entrance to the castle. It is unknown why this scene was not played in the arcade version, but the European release and most home versions include it. Most recent versions even allow you to choose between the arcade and home versions, the home version including the drawbridge scene. There are a few other minor deleted moments in the arcade version that were restored to home editions, but the drawbridge scene is the most obvious.

Dragon’s Lair was a smash hit both in arcades as well as at home. Although many of the early home ports had to take major liberties, due to the inability to replicate the animation. Once CD-ROMs became mainstream in the early 1990s, it was much easier to port, due to the far greater storage space available compared to cartridges or floppy disks, and early consoles to use the technology were given ports, including the Sega CD, 3DO, and CD-i.

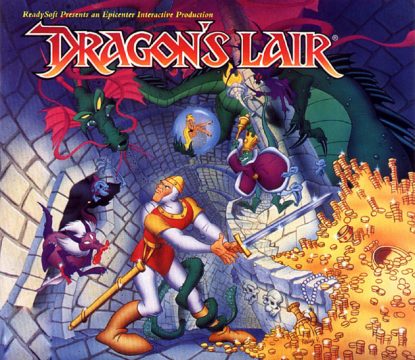

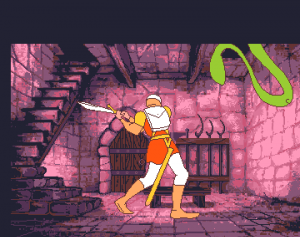

One of the first ports to really capture the spirit of the original was the Amiga version developed by Visionary Design Technologies, headed by Randy Linden (who would later be known for creating the Playstation emulator Bleem!), and published by ReadySoft (which would later create the Dragon’s Lair clone Braindead 13). By using rotoscoping to separate the characters from the backgrounds, and then redrawing both to work within the graphical limitations of the Amiga, Linden and his team managed to squeeze several rooms of the game onto six 3.5” floppy disks, a massive technical achievement for the time. Despite its long loading times and finicky controls, it was the best home version available at the time by a wide margin, although not really worth fiddling with today.

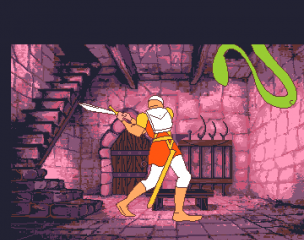

The Sega CD version suffers greatly due the limited amount of colors the system could display on-screen, resulting in massive dithering of Bluth’s animation. If that were its only problem, it would still be a decent port for the time, but it also suffers from many other problems as well. A lot of the animation, especially more complex parts, has been cut, to the point where the intro had to be re-edited almost from scratch, and doesn’t match up with the audio.

The gameplay is also rather suspect in this version, as it gives no acknowledgement to the player as to whether they are making the correct moves or not, which is a real problem due to the fact that some levels have different moves than the arcade. On top of that, the controls don’t feel right. You would think that it would be hard to mess up the controls for an FMV QTE game, but somehow, they did. The game’s move timing is noticeably off, requiring you often to make moves before it’s really clear what you are supposed to do. Even worse, some of the input windows are too wide, meaning if you tend to repeatedly tap the required input to make sure it goes through, you risk the game thinking you’re making the next move and killing you, as it only recognizes the first input you make during that window. This often results in the player getting killed even if they know the correct moves, making this version very frustrating. However, the worst design choice of all is saved for when you continue. The game has a checkpoint system, and when you continue, you go back to the first of that set of rooms, meaning it is quite easy to be sent back several rooms, and being forced to slog through them again. All these massive issues make the game painful to play, and one of the worst ports.

One of the biggest surprises is the Game Boy Color port (not to be confused with the game for the original Game Boy, which will be covered later) developed by Digital Eclipse and published by Capcom. It is shockingly good considering the very limited hardware. Many of the rooms are intact, albeit with greatly simplified animation and sound, and the controls work great. It’s definitely worth a look for the curious. There are far worse ways to experience Dragon’s Lair.

On the subject of incredible ports, in early 2019, an officially licensed port of Dragon’s Lair was released for the Texas Instruments TI99/4A, created by Tursi of HarmlessLion. Taking into consideration the hardware, the fact that the game is running as well as it does is shockingly impressive. The complete game is represented, with both Arcade and Home versions playable, and although compromises had to be made in terms of video resolution and quality, this version would have brought the house down if released during the system’s heyday. Unfortunately, only 100 copies were produced, and the game is sold out. Here’s a link to a video of it in action: https://youtu.be/QB3oHdSjfCE

Although it spawned many imitators, when people fondly reminisce about laserdisc arcade games, they are most likely thinking about Dragon’s Lair. It is without a doubt the iconic game of the genre.

Screenshot Comparisons