Before Final Fantasy VII made Japanese RPGs the talk of the town, only a fraction of them made it to American shores. In Volume 2, Issue 8 of Diehard GameFan, K. Lee addresses this issue, stating that “too many times, great Japanese RPGs (Konami’s Madara 2 for example) get passed over because, somehow, American 3rd party companies believe there is a very limited market for role playing games in this country!” This was especially true during the NES era, where Nintendo themselves localized and published Dragon Warrior and Final Fantasy . Both were heavily advertised in Nintendo Power with coverage in four issues or more. Eventually, Dragon Warrior was even given away for free with a subscription to the magazine. Obviously, Nintendo-published JRPGs were going to get a lot more press than everyone elses.

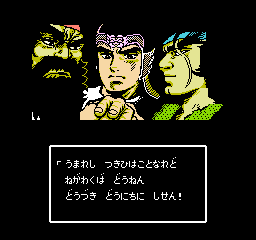

That’s what makes Destiny of an Emperor‘s appearance in September 1990 so odd. Not only is it one of the few RPGs released for the NES, but the box discusses an ancient Chinese and thus incredibly Eastern setting. While many discuss how games like Totally Rad had their Japanese elements supplanted with distinctly American features, with characters transforming from anime cuties to teenagers spouting out surfer slang, exceptions to this alleged rule existed. Computer Gaming World and Nintendo Power heaped praise on Koei’s historical simulation, which were coming out in rapid succession around 1990. Featuring ancient Japanese and Chinese warlords battling to unify their respective countries, Koei continued to release these games in America with mild success. Perhaps this sort of response was what Capcom USA expected for their similarly themed game.

Unfortunately, the game received very little coverage in the press, with Nintendo Power typically mentioning it only in their Pros’ Picks column, a list of the Nintendo Power staff’s favorite games. Destiny of an Emperor faded into relative obscurity as most third-party JRPGs did. What few professional reviews do exist are brief blurbs from The Video Game Bible and allgame.com, both of which champion its innovative gameplay without really going into any specific details.

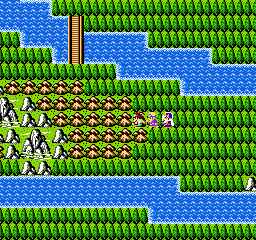

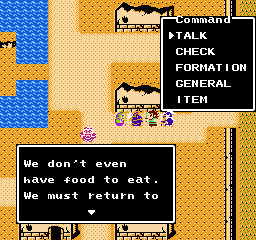

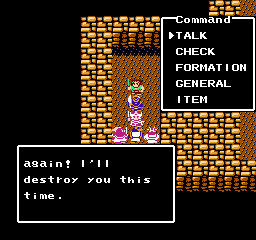

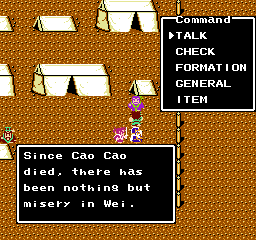

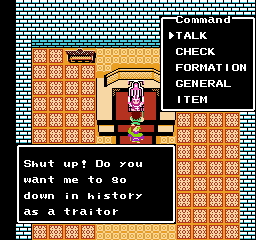

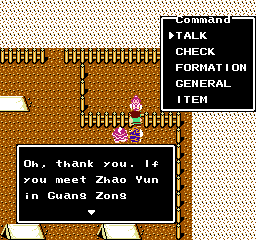

Upon starting the game, you’re greeted with mechanics awfully reminiscent of a typical Dragon Quest clone. You have a talk action, a search action, stat menus, party options, and inventory access. As usual, the villagers typically offer information and clues. The characters look pretty ugly, although they exhude an NES RPG charm. The sprites might as well have been drawn directly from Dragon Warrior II, replacing the generic medieval armor with those of ancient Chinese folklore.

The first noticeable difference is the walking speed of your character. For those who complain early JRPGs have horrible walking speeds, take refuge in the fact that Destiny of an Emperor‘s player characters move five times faster than you’d expect. Additionally, the game also provides Gullwings, items which allow you to instantly travel back to previously visited castle. Getting around so swiftly makes the game more palatable than the typical JRPG, though the encounter rate remains unforgiving.

On the subject of walking, the characters constantly need to eat food in order to survive, an element typically found in early western RPGs. The game begins with 1000 food, but with each step, one food is spent. If the player runs out of food, the screen starts flashing red with every step and hit points for every general are dropped by one, similar to a poison status in JRPGs. This insatiable hunger quickly becomes a problem in the early stages of the game, where grinding against low level enemies who don’t reward food is a necessity. This also becomes a problem when the player is trying to buy better equipment, as one quarter of the gold that was going toward a new weapon often gets spent on 300 pieces of food.

It’s pretty obvious that battles are the game’s intended focus. There are only a handful of characters in towns, and very few ever progress the storyline. This might be a problem in JRPGs with limited options, but the battle system has enough depth to last for the duration of the game.

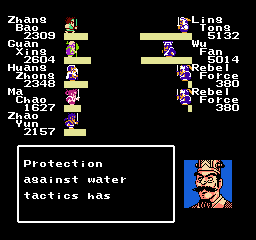

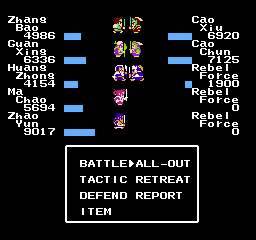

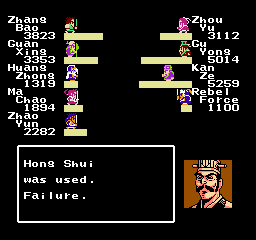

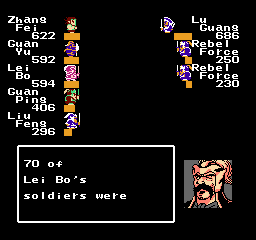

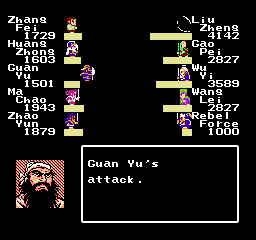

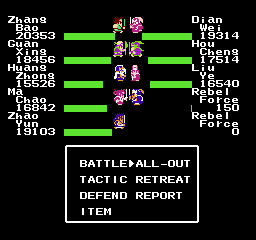

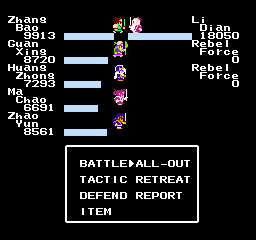

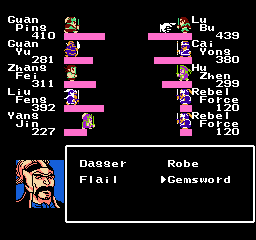

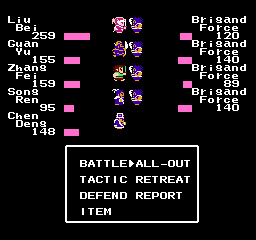

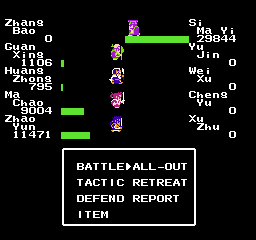

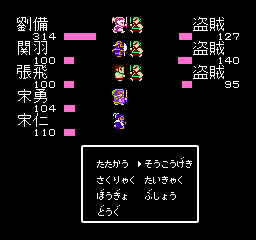

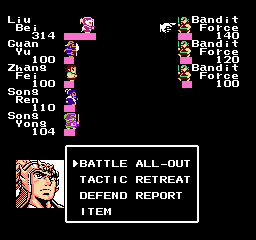

Many people label Destiny of an Emperor a strategy RPG, which isn’t totally accurate. While there are dozens of distinct playable units throughout the game, battles aren’t fought on a battlefield like Fire Emblem or Shining Force. Instead, five player controlled generals are pitted against five enemies on a single battle screen. The player has seven openings in their active party, but only the first five are on the frontlines. Sometimes the enemies will be generic outlaw or pirate army units, but usually they will be named generals. In a sense, there are literally hundreds of unique boss encounters to be found.

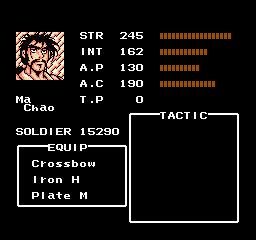

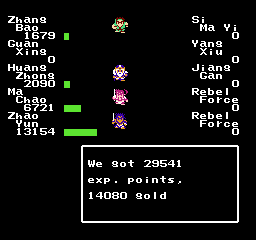

Generals attack ability is dependent on two things: stats and army count. All characters, including player controlled ones, have a set amount of strength and intelligence that remain static throughout the game. Strength dictates physical attacks and intelligence determines the power of magic attacks. The former is the biggest problem throughout most of the game, as stronger generals can knock off half of a character’s hit points in one strike. If pitted against four generals, your party can easily get wiped out without some forethought. As army count also is a factor in character strength, battles frequently become more about balancing out what enemies need to be neutered first. You could spend an extra two turns attempting to totally kill an enemy, but if the next opponent is still whacking off 1000 of your character’s armies, it’s best to balance your onslaught to minimize damage from the enemy.

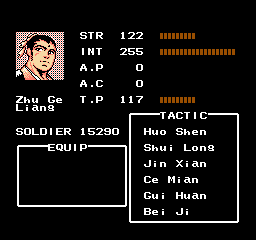

Even worse, some enemies are incredibly adept with magic attacks. Mastering these becomes crucial, especially in the later stages of the game where enemies will exploit full heal and instant death abilities. Referred to as tactics in the game, only a handful of characters with reasonably high intelligence learn these skills, yet anyone can use them.

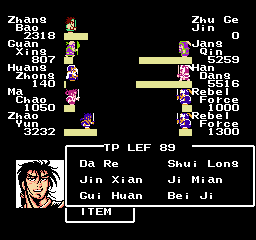

In order to use tactics, you need to select a character as your strategist on the formation menu. Whatever skills they know can be used by any character in your main party. Usage of these abilities drains tactical points, basically magic points, which generally limit your offensive and healing spells to around ten usages. Max tactical points increase as the game goes on, but older, weaker abilities are constantly being replaced by stronger powers that consume more TP, making it difficult to exploit them.

There are a few types of abilities that are staples throughout the game: fire, water, and healing tactics. If a battle occurs on land or in a dungeon, fire tactics may be employed during battle. Fighting near water allows you to use the more powerful water attacks, though these consume more TP. Healing spells initially waste a lot of TP, but very late in the game you gain access to Jin Xian, a skill that heals every party member for 4,000 soldiers at the meager price of four TP. In a stroke of genius by the game designer, it’s only learned by Zhuge Liang, a powerful strategist who is incapable of learning An Sha, the game’s instant death spell.

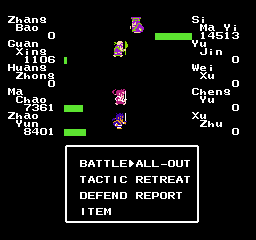

Near the end of the game, when enemies constantly use both powerful offensive attacks and full heal spells, having a back-up strategist in tow to either go into battle with a powerful healer or an instant killer isn’t a bad idea. Most generals will have between 30,000 and 40,000 armies, a number that your characters won’t reach even after hitting the level 50 cap. With the ability to effortlessly knock off 15,000 armies, use powerful full party offensive spells, fully heal anyone, and cast An Sha, these battles might feel wholly random, but strategically weakening specific generals and masterful use of tactics yields success. It’s truly difficult, but never unfair, a balance that many games never reach.

One of the nice additional features of the battle system is the “all-out” option, which causes all of the warriors to dash to the middle of the screen and start randomly attacking one another. In boss battles, this is basically a suicide button. While strategy is crucial to succeeding in key battles, the quick battle is a good option to use against enemies you know are either inherently weak or severely weakened. Breezing through the easier battles will keep you from falling asleep before you rush the next castle.

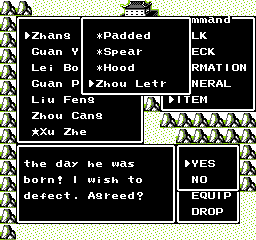

Although the game begins with only three generals, it quickly becomes evident that many more can be recruited. Characters in towns will occasionally offer to join your party, but most of the generals aren’t so casual, requiring you to defeat them in random battles on the overworld or in dungeons. After defeating a general in the wild, an option will be given to recruit them. Some will join up immediately, while others demand some sort of payment. As the game moves on, this price goes up considerably, but there’s always the option to deny payment, beat them again, and see if they’ll join for free. There’s 150 recruitable generals throughout the game, though only 70 can be in reserve. Once 70 generals are recruited, the weak must be dismissed to make room for the strong. Discharged recruits will simply return to the area they originally roamed, allowing you to recruit them again if you so choose.

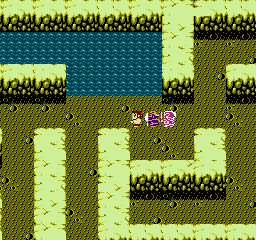

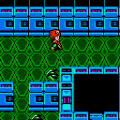

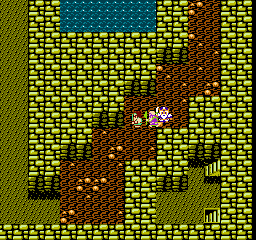

Exploration is pretty limited, with the overworld feeling more like a linear path than a realm filled with mystery and intrigue. While the ultimate goal is to conquer castles by winning fixed boss battles, much of the game follows this formula: people in town will tell you where to fight next, rush there and destroy, people in that town will tell you where to fight next, and so on. Some of the areas between castles are large, but they’re almost always vacant of any real features. It might as well have been corridor, boss fight, corridor, boss fight a la Final Fantasy XIII. Add to this that every castle, mountain, tree, and cave looks absolutely the same, and exploration looks and feels pretty monotonous.

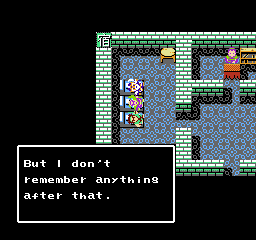

Following the basic twisting corridor pattern of most JRPGs, there are only five dungeons in the entire game. While they’re often the location of an important quest item, none of them are particularly long, with the smallest one being one short floor and the largest one fully traversable in less than ten minutes. Despite this, Destiny of an Emperor‘s main focus is dynamic battles, so the limited exploration and brief dungeons keep the player focused on progressing through the game. Along with the walking speed and “all-out” option, it reflects a general design decision to make the game fast-paced, a nice touch that keeps the game from getting too monotonous.

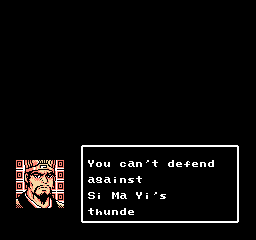

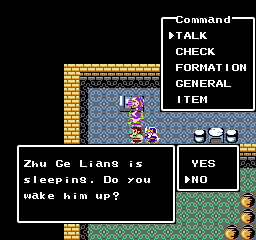

There’s a lot of other novel little story touches that break up the constant stream of battles. One of the best parts is near the end, where an enemy named Si Ma Yi instant kills your entire party with a thunder attack. In order to negate his attack, Guan Sun tells you to put in a specific button combination right before he uses it. Another interesting event is finding Zhu Ga Liang, who is sleeping when your party catches up with him. While Zhu sleeps, it gives you the option to wake him. Selecting yes does nothing, but picking no leads to a ten second wait after which Zhu rolls out of bed and joins your army. Although these moments aren’t too phenomenal, they certainly are memorable.

Several other key design choices fall apart by the end. Eventually, boss battles reward the player with more than enough food to last the entire game three times over. Likewise, money ceases being a problem around three quarters of the way through. Only the Five Tiger Generals, Zhang Bao, Guan Xing, Zhao Yun, Ma Chao, and Huang Zhong, increase in armies as you level up. As their armies grow, so does the strength of their physical attacks, making them an obvious choice over the other hundred plus playable characters. Still, these key game elements only fall apart near the end of the game when you’re more worried about over-powered opponents, so it’s more of a shift from worrying about buying the next weapon or more food to worrying about whether a general will instantly kill you with an An Sha. If anything, the change in focus is pretty masterful considering how high the difficulty gets.

On very rare occasions, the game does force you to back-track a little which leads to the game’s worst moments. The aforementioned search for Zhu Ga Liang involves traveling all the way back to the beginning of the game just to realize he’s not there, then back and forth between several other key areas. This only happens three times throughout the games fifteen to twenty hour duration, but it’s a pain nevertheless.

On very rare occasions, the game does force you to back-track a little which leads to the game’s worst moments. The aforementioned search for Zhu Ga Liang involves traveling all the way back to the beginning of the game just to realize he’s not there, then back and forth between several other key areas. This only happens three times throughout the games fifteen to twenty hour duration, but it’s a pain nevertheless.

Overall, this is just nitpicking. Considering this is Capcom’s first RPG, it’s surprising how sharply designed it actually is. The game design is credited to Yoshiki Okamoto and Yoshinori Takenaka, both industry veterans. Okamoto produced many popular Konami and Capcom titles, including Gyruss, Time Pilot, Final Fight, various Mega Man titles, and many of the company’s fighting games. Takenaka previously worked on the classic DuckTales NES game. After Destiny of an Emperor, he went on to do design work for several Mega Man games, the first Breath of Fire game, and, more recently, Folklore. Both have continued their working relationship into the current millennium, working together on games like Knights Contract for PS3/360, Dragon Ball: Origins for DS, and Brave Story: New Traveler for PSP. It’s refreshing to see professional collaboration like this continue after over twenty years. The producer, Tokuro Fujiwara, has a massive list of credits, producing tons of NES classics: DuckTales, Gargoyle’s Quest, Chip ‘n Dale, Mega Man titles, Destiny of an Emperor and its sequel. His latest credits include producing and directing Hungry Ghosts and providing original game design for Madworld. With such renowned talent, it’s no wonder Destiny of an Emperor‘s battle system and quick pace are so well-executed.

Another key player in the game’s development is Hiroshige Tonomura, the sound programmer. The soundtrack for Destiny of an Emperor recalls the bouncy, melodic approach of DuckTales, which was also Tonomura’s first assignment at Capcom. Imagine the tuneful tones of that game occasionally filtered through some eastern-sounding melodies, which are appropriate considering the ancient Chinese setting.

Destiny of an Emperor is truly a forgotten gem, an overlooked game with enough unique and solid elements to warrant attention. Sequels excluded, there’s no other game quite like it, and while archaic JRPGs aren’t for everyone, it’s mix of complex battles and straight-forward progression make it far more engaging than most.

Destiny of an Editor – PC (2007)

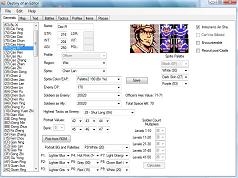

Since the dawn of gaming, development tools that require absolutely no programming knowledge have always existed. A little hex editing knowledge and a lot of effort has led to some really great hacks/mods of NES classics, but there are programmers out there who want to make NES hacking easier. With Dungeon Master and Zelda Tech, anyone can efficiently generate their own Zelda mod complete with second quest. In 2007, Destiny of an Editorappeared, completely done by Niahak as part of a project for the Lord Yuan Shu Forums.

Over the next few years, the editor went from a simple stat altering tool to a full-fledged game creation tool, allowing you to edit all text, maps, enemy encounters, and graphics in Destiny of an Emperor. There’s no tutorial required as the various functions are very intuitive, although making a full-fledged game will still take a great deal of effort. Altering generals’ stats, locations, and encounters takes quite a bit of forethought, let alone filling a new world map and storyline with these characters. Much of the editing is a simple matter of changing around some numbers, clicking different tiles, or altering some text. The text editor is actually the most difficult feature to master because it’s not exactly clear when, where, and with which characters the dialogue occurs.

As Destiny of an Editor has improved, so has the quality of the hacks. Early hacks like Destiny of an Emperor 2.0: Cao Cao Edition are mostly cosmetic alterations, created before the map editor was introduced in 2009. In essence, these mods merely introduce new main characters and occasionally ramp up the difficulty. After the map editor was introduced, more quality mods were being produced, which lead to the Huan Ho awards, an annual acknowledgement of quality work in the Destiny of an Emperor modding community. The small scene continues to thrive on the Lord Yuan Shu forums, making more and more games that improve and expand upon Destiny of an Emperor‘s formula.

Featured prominently on the forums, Yuan Shu, Yuan Shoa’s Revenge, Rise of Lu Bu, Rise of Ieaysu, Flames of Wu, and Tyrant Dong Zhuo are the focus of the community, all of which can be downloaded here at the Lord Yuan Shu forums. For each of these, the game appears to be significantly altered. The world map and character graphics are significantly altered, and several of the game’s introduce entirely new battle elements. MiDKnightT won a Huan Ho award in 2012 for adding duels to the game. Duels are cast by the player, and if the computer opponent accepts, they’ll dash forward to the screen and go all-out against one another. The article describes in details all of the stats involved in this, but after all is said and done, the loser dies and the victor receives a stat boost. Rise of Lu Bu mod is particularly striking, amping up the difficulty, vastly improving the dungeons, and opening the game world for greater exploration.

With development times ranging from two to three years, and several in a continuous state of development, these Destiny of an Emperor mods are a labor of love. For the quality of their alterations and enhancements, the scene is disappointingly ignored by much of the hacking community, which is a shame considering their efforts are more worthwhile than most of the official sequels.