Regardless of your opinions of the genre, horror movies can be a bit difficult to relate to or care about. It’s difficult to find zombies to be “cool”, or to still jump after the bazillionth time you see the whole monster-jumps-out-and-yells-“BOO” routine.

When it comes to horror themed video games, an inability to relate to their themes is less of a concern, because they can always be ignored in favor of gameplay. As they are secondary to actually playing the game, it’s arguably easier to make horror movie themes effective in video games than in movies, because they aren’t over-powering everything else. While their plots are almost always stolen wholesale from horror movies, it’s much easier to care about what’s going on when YOU have to worry about something jumping out at you. The gameplay is almost always set up to assure that you have to proceed with maximum caution, so it’s much easier to keep your attention this way than if you are passively watching it like with a movie. Think of the 2006 film rendition of Silent Hill – it was stylistically very faithful to Konami’s survival horror series, but as the player is divorced from the protagonist, it ended up feeling kind of silly.

There had been a few horror-themed games in the past, such as Infocom’s Lovecraft-inspired “The Lurking Horror“, but none of these appeared on home consoles. Capcom’s 1989 Famicom title Sweet Home (Suīto Hōmu) was released several years before the term “survival horror”, coined by Resident Evil, even existed. So, not too surprisingly, it’s a more primitive representation of the genre’s conventions than games like Resident Evil or Silent Hill. Yet everything that defines those series as survival horror games is here as well: the overwhelming sense of dread, the unnerving presentation, and the emphasis on character preservation and item management. It even has multiple endings like so many modern survival horror games. Where it really differs from modern survival horror games is that it’s all put together in the form of a RPG. It isn’t as passive or relaxed as most RPGs, though. The tense nature of its gameplay is surprisingly similar to modern survival horror games. The only real RPG elements that aren’t in other survival horror games are experience levels and random battles. The original Resident Evil even began as a remake of Sweet Home. It eventually evolved into its own game, but all they really did was change the setting, lose the RPG elements, and utilize polygonal graphics. So between its innovations and its influence on Resident Evil, it’s pretty much the game that defined the entire genre, elements can be seen in virtually any survival horror game today.

Sweet Home‘s horror movie thematics and presentation style aren’t the least bit coincidental. It’s actually based on an obscure Japanese horror movie of the same name. In fact, both were released at the same time, and the trailer for the movie also promotes the video game and contains footage from both. There are a few differences between the movie and the video game, but many images are very similar. The director and writer of the movie, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, is also credited as supervisor for the game. As the game’s credits amazingly reveal, famed director Juzo Itami served as producer for the game. He was also executive producer for the movie and played the character of the old man at the gas station. It’s very hard to come by a copy of the film, even in Japan, where it has yet to be officially re-released on DVD. The only real way to see it is through bootlegs, but its legacy lives on the video game.

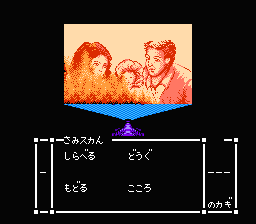

The movie and the game begin in the same way – a team of five people setting out to the abandoned (and apparently haunted) Mamiya manor in hopes of capturing the painter Mamiya Ichirou’s final fresco on film for a documentary. Each character begins with their own permanent item that either makes survival much easier or is required for progress at various points.

Characters

Kazuo Hoshino (星野 和夫)

Kazuo leads the crew of five that are involved in making his documentary. His item is a lighter that is mostly for burning ropes and lighting candles. His HP is the highest, so he makes for a good “main” character.

Akiko Hayakawa (早川 秋子)

Akikio is a nurse. Her item is a medical kit that will heal all status ailments, but does nothing to restore health. Like practically every other healer character in RPGs ever, she is relatively low powered.

Ryō Taguchi (田口 亮)

Taguchi is Kazuo’s cameraman in charge of filming his documentary. As would be expected, his item is a camera with which he can take pictures of the many frescoes in the mansion to reveal hidden messages. His defense is the highest in the game and he has good HP.

Asuka (アスカ)

Asuka is a maid. Her item is a vacuum cleaner that will remove dust from frescoes and vacuum up broken glass from floors. She is the second lowest powered character in the game.

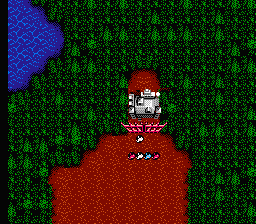

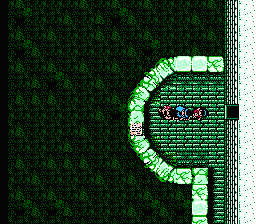

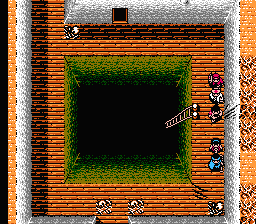

A very specific atmosphere has been created for Sweet Home that borrows more than a few tricks from movies, as well as RPGs, but applies them brilliantly. Throughout the game, the setting and events are established with a very minimalist approach, and its intro exemplifies this. The game opens with an aerial shot from WAY above Mamiya manor, followed by our heroes approaching its gate within the same shot. Not only does this introduce the characters and the player to the setting, and begin the events of the game, but it also establishes the location of the mansion itself. Mamiya manor is located out in the woods near a pond with no other visible structures nearby. So even though this fact never comes into play later in the game, you play the entire game aware that this is an isolated locale and that these characters are completely alone – greatly enhancing the atmosphere of the game, and all conveyed with a lone shot.

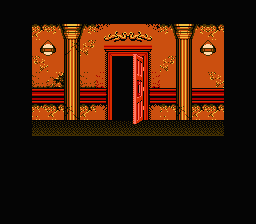

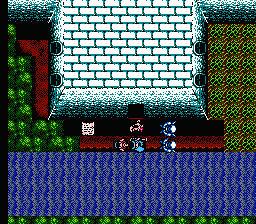

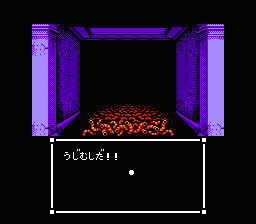

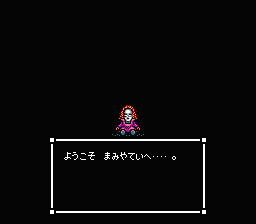

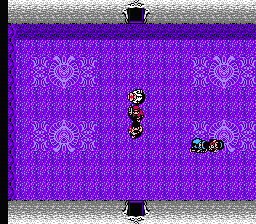

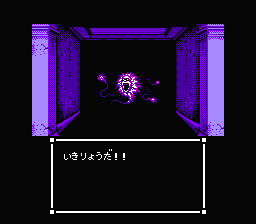

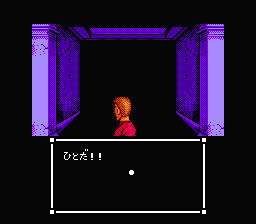

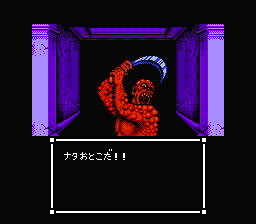

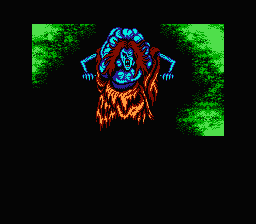

From this prologue, you are taken to a close up of the front door to the mansion being opened as the characters enter Mamiya manor. The strong contrast between the distant aerial shot and the close up immediately forces your own perspective directly into the game’s setting and creates a sense of your own “entrance” to the game world. That they did this with a shot of a door being opened further enforces this. After the five characters move into the small room at the entrance of the mansion, the door slams shut and a ghost appears – it begins threatening you and then disappears. At this point, you’re given control of the five characters to find a way out of the mansion.

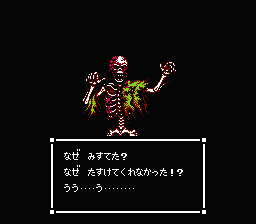

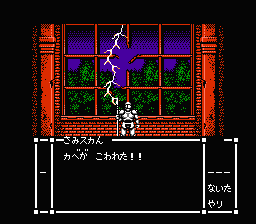

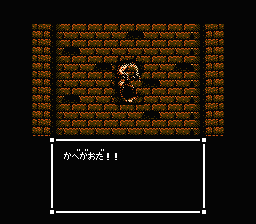

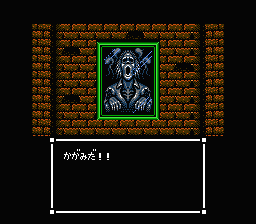

The plot is not very different from your average Japanese horror movie, but the way the story is told is extraordinary. It’s told as much with words as it is through the process of discovery – a technique that would be impossible in a movie, and allows a fairly generic horror plot to have a much greater impact than it could have outside of a video game. From this point on, much of Sweet Home‘s plot is revealed through diary entries and messages in paintings that can be found throughout the mansion. The thing is, these diary entries and paintings are entirely optional. You can avoid them completely and the game will progress without any problems. There are few actual plot scenes in the game, as well. What events, objects, and places are encountered through your own actions is as important a story telling tool as any plot scenes or dialog in the entire game. Whereas many other games practically scream “LOOK AT THAT!” whenever there is something important on screen, in Sweet Home there is often little or nothing to give an image any significance other than your own powers of observation. This subtle approach has amazing results, and much of the imagery in the game totally messes with your head when it’s first encountered.

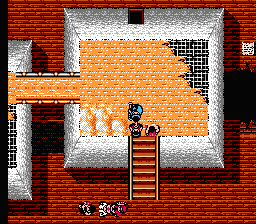

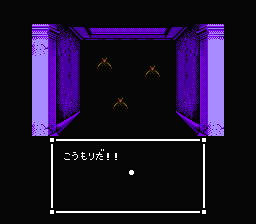

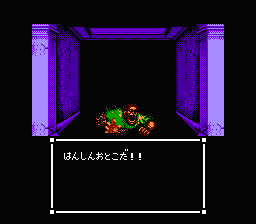

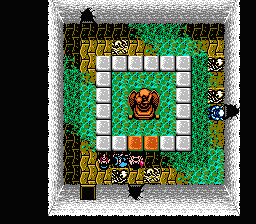

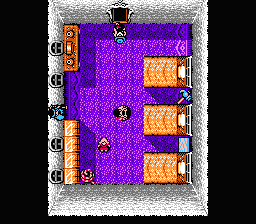

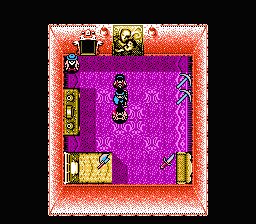

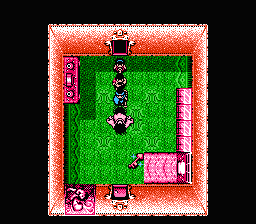

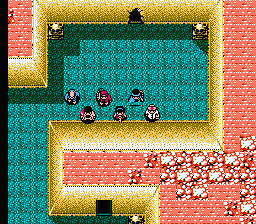

This kind of atmosphere-enhancing story-telling never stops in Sweet Home. Many of the rooms in the game, like the room you begin the game in, don’t take up very much of the screen. It might seem pretty much pointless to have less on screen than possible, but it’s amazingly effective at giving the game a claustrophobic feel. Mamiya manor as a whole is absolutely huge, and comprises of countless rooms, hallways, and wide open areas. Getting lost is only a major problem if you haven’t been paying attention, but the immense size of the mansion enhances the feeling that your characters are trapped within its vast expanses. Certain areas early in the game require a candle to be navigated. These candles will only make an area a few spaces from your characters visible, so you have to make your way through these sections with extreme caution.

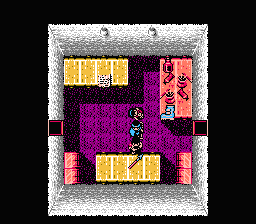

Another area of gameplay that creates a constant sense of caution lies in how you change between characters. Rather than having a lone party lead by a main character, you control each of the five characters individually and can switch between them at any time. You can group them into parties however you like, but you cannot have more than three members in a party. Not only do you have to worry about multiple parties at once, but there will always be at least a single group that lacks enough characters to safely explore the mansion without putting them at serious risk. An easy way to solve this is to pick a character to be your main character and have them move with a party of two other characters, then backtrack to join up with the other two and move them to where the first group is, so that everybody always stays close together. This might seems like it would get really repetitive, really quickly, but your main character will quickly over-level and easily be able to take care of themselves.

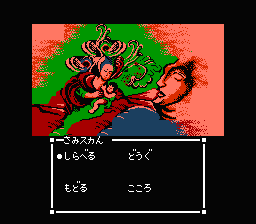

While navigating the mansion, you can check the status of each character by pushing the B button, or bring up a multitude of commands by pushing the A button. The first of these commands is “Party”, which will allow you to switch to control of a different character. The second command is “Item”. This will bring up the inventory of each of your compatriots, or the inventories for your lead character and any character outside of their party that they are facing. You can exchange items, do whatever is needed with an item when next to something it’s needed for, or move an item into your inventory by selecting “Move” and then selecting a empty space in your inventory. Another way that Sweet Home strongly differs from most other RPGs is that you only have two spaces in your inventory for items and a lone space for weapons. So if you have no more room, then you have to leave an item behind to pick another. Keeping only the most important items is absolutely essential, and managing your items correctly is crucial at key points in the game. You do have the option of leaving behind even the most important items, but you’ll have to remember exactly where they are at when you need to go get them later.

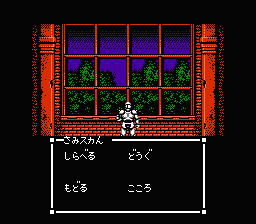

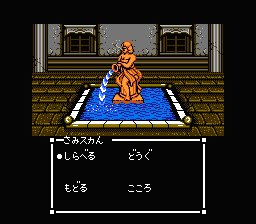

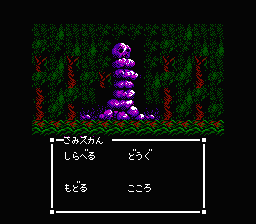

The third option is “Talk”, which will talk to any character you are facing. The fourth option is “Team”, which will team up your current character with any character they are facing. If that character is in a party of two, and your character is alone, then you will team up with both characters. If you are not facing anybody, then selecting “Team” will separate your lead character from the rest of their party. The fifth option is “Look”, which is for inspecting anything you are currently facing. Anytime this brings up a closer view of the object you will have four more commands to choose from: “Look”, “Item”, “Leave”, and “Pray”. “Look” will further inspect whatever you are looking at. “Item” will bring up your inventory in case something you have can be applied to whatever you are looking at. “Leave” will go back to the previous screen.

Sometimes, you’ll need to Pray for certain items to work properly. When you pick this option, a meter will appear that moves back and forth rapidly. The closer it is to the right when the A button is pushed, the more powerful it will be, and the more Prayer Points will deplete. Each character has a limited amount of Prayer Points to begin the game. Leveling up in raise their maximum amount of Prayer Points, and healing will completely replenish their prayer meter. Outside of battles, it will be ineffective if it is not powerful enough. So if you need to Pray to make something happen (like activating an event after doing whatever with a item), and the meter is not far enough to the right, it won’t work. The sixth option is “Save”, which is self-explanatory. You can save anytime, which is quite handy.

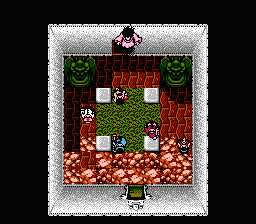

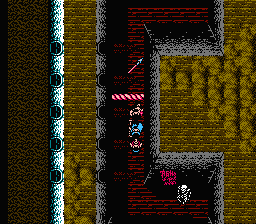

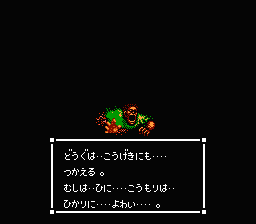

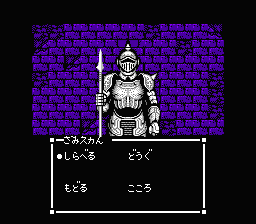

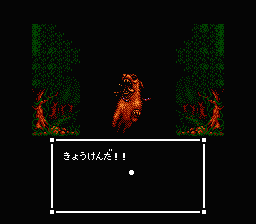

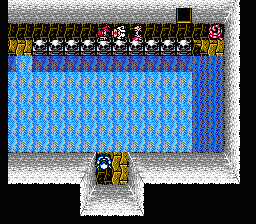

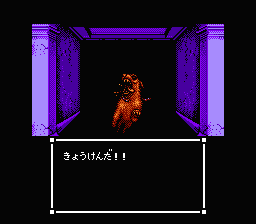

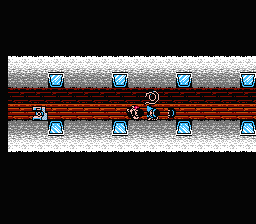

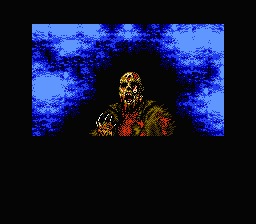

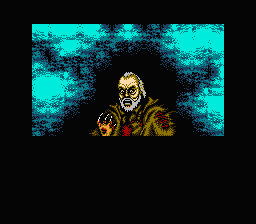

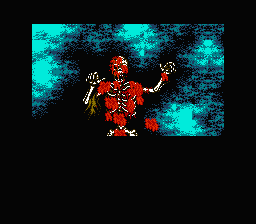

Along your way through Mamiya manor, you’ll encounter a multitude of horror movie-style monsters. A couple of sections have bats or knights visible on screen, but otherwise every battle is randomized. Battles play out pretty much like the early Dragon Quest games, where you stare at a static image of your enemy and do nothing other than select your move. You have five options to choose from for each battle: “Attack”, “Pray”, “Tool”, “Run”, and “Call”. “Attack” is self-explanatory. “Pray” also brings up a moving meter like in other segments, but will work as an attack. “Tool” will allow you to attack with an item from your inventory if you have anything that can work as a weapon. “Run” will give your character about a 50% chance of escaping a fight. This can be extremely valuable in certain circumstances, so don’t feel like you need to fight every enemy you encounter. Lastly, “Call” will allow you to switch to a character out of battle. This is even possible with more than three characters, so don’t hesitate to do this if you get in serious trouble. You always get to attack before the enemy, so as long as you’re properly leveled and have a party of three then you can defeat many enemies before they can get in any attacks themselves. A few enemies can potentially cause various status ailments that can lead to major league problems if they are not cured quickly.

There are a few other dangers that don’t necessarily directly relate to combat. There are several kinds of terrain that can damage your characters if you don’t have a certain item, and it’s possible for a bridge to break while a character is walking across it. If this happens, their health will begin to deplete, but you can team up with them to save them. There are a few sections of the game where ghosts are roaming around on the map. If a ghost makes contact with any character, they will be transported to a remote area that is generally within a relatively brief walking distance.

Sweet Home makes a few other deviations from your standard RPG formula. Since it takes place entirely in a lone mansion, there aren’t any shops or anything to buy. So it’s no surprise that monsters don’t leave behind money, but they don’t leave behind items either. Everything in the entire game has to be obtained from the mansion’s many rooms, and nothing can be replenished or replaced. There isn’t any magic system either. The “Pray” command during battles might be a relative equivalent, but there are no actual magic spells to acquire. The only way to actually heal your characters is with Tonics. These will heal everybody in your party, but once there are no more Tonics left in the mansion, there is no way to heal any of your characters. To make it even more difficult, every character death, without exception, is permanent. Without the standard RPG option of “revive character, heal at inn” after every fight, the game’s battles never become irrelevant and you are kept from being able to simply plow through the game carelessly, further heightening the level of caution the game has to be approached with. Technically you can find replacements for many of each character’s individual items, so it’s not like the game can become unwinnable. But there are also five different endings, and which you get is determined by exactly how many characters survive.

Sweet Home‘s atmosphere is enhanced as much by its story telling as it is by its graphics and music, which are among the best for the Famicom. The individual visuals are really not anything that you wouldn’t see in a bazillion horror movies, but the 8-bit sprite art greatly benefits their presentation. The pixelation to the graphics makes everything grittier and that much closer to the old horror movie poster-style illustrations that obviously served as inspiration for the game’s aesthetic. The music is modeled after the style of film score popular in 1980s horror movies. As great as it is, the style is a bit predictable given the theme of the game. Other than the high caliber of the compositions themselves, what really makes Sweet Home‘s music work so well within the context of the game is that it actually becomes much eerier as 8-bit chip music than it would if it were orchestrated.

Sweet Home is remarkably impressive for its era, and among the best RPGs for the Famicom. It’s incredibly impressive just to see how ahead of its time it was. With the game never having been released outside of Japan, it may be a bit difficult, if not impossible, to play through if you don’t speak Japanese, but there are two translated versions of the ROM out there by Gaijin Productions and Suicidal Translations.

Links:

RPG Classics Great database of stuff.

Sweet Home Has screencaps of EVERY shot in the entire movie in order. So it’s like watching the entire movie as a series of stills. Especially interesting if you have already played the game. Possible SPOILERS if you have not.

Video Game Museum The ending.