After Minstrel Song on the PS2, it would be a very long time before a new SaGa game was developed, but its eventual worldwide debut would represent a major pivot in Square Enix’s game release strategy. No longer confined to a single console, every new and re-released game would have a multiplatform release. But what could a new entry in this ever-experimental series even look like? Would we see a more conservative game intended for a larger audience? Something that would draw on the series’ roots? Or something completely different? What lessons may have been learned from 2005, the last time any part of the world saw an entry to this game series with roots as nearly as old as the company itself?

Scarlet Grace (2016) (released internationally as Scarlet Grace Ambitions in 2019) would in fact make some radical changes to the formula, stripping a choice-heavy role playing game to just a few essential elements. So when you can’t do everything, what do you keep?

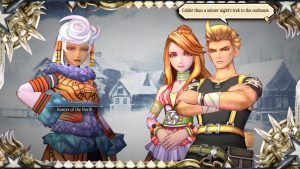

In the game created by the debut of the “SaGa Project” a lot of that SaGa essence is completely intact. You still have a series of scenarios and an amazing amount of freedom to choose from among them. There are many interlinking systems with secrets to discover, not just in the game world but between the mechanics themselves. There are still multiple protagonists; however, this entry features four instead of eight, each paired with their own deuteragonist. While concepts like “dungeons” and “explorable towns” are completely gone, your time in each of the world’s twenty regions will present a vast series of quests and strategic choices, both large and small.

The world of Scarlet Grace is introduced in a cut scene (absent in the mobile version and strangely requiring players to play it manually on the PC version) featuring striking pans across a mosaic depicting the world’s vast history. The Firebringer, (a promethean figure who has literally fallen from grace) opposes the Emperor chosen by the twelve Celestial gods of the world. The game picks up after this empire succeeds in finally striking down the Firebringer, thus losing its uniting purpose and collapsing into bickering between the great houses. The four protagonists set off to explore the vast regions of the world, getting clues about the real story behind the motives of all these divine beings and uncovering mysteries in each of the game’s regions.

The world of Scarlet Grace is introduced in a cut scene (absent in the mobile version and strangely requiring players to play it manually on the PC version) featuring striking pans across a mosaic depicting the world’s vast history. The Firebringer, (a promethean figure who has literally fallen from grace) opposes the Emperor chosen by the twelve Celestial gods of the world. The game picks up after this empire succeeds in finally striking down the Firebringer, thus losing its uniting purpose and collapsing into bickering between the great houses. The four protagonists set off to explore the vast regions of the world, getting clues about the real story behind the motives of all these divine beings and uncovering mysteries in each of the game’s regions.

Like nearly all of the other games of the series, you are given a lot of freedom to explore and pursue the game’s major quests, with each protagonist focusing on one of them. Kenji Ito’s music remains a strong supporting presence with unique overworld and battle themes for each of the four protagonists.

Leonard

A simple farmer with a giant sword. Doesn’t have a lot of patience or understanding for all of the weird events going on around him but listens as his pal Elisabeth explains things to him. Oh, and apparently he was born with a scarlet shard in his hand. That probably will be important later…

Elisabeth

The second half of Leonard’s story. She is the daughter of a wealthy family whose traveling experience gives her a lot of insight into the way the world works. She also brings her own entourage and a wicked powerful frying pan.

Urpina

A noblewoman of house Julanius which is one of four noble houses. Her house is famous for two things: swords and using one of them in each hand. She and her house represent a modicum of order after the fall of the empire. Very informed and dutiful to the Celestials.

Mondo

Experienced and level-headed retainer of house Julanius. He is an effective and strong warrior, but his age is certainly getting to him. Like the spear he wields, he is very versatile in the quest to save Urpina’s brother and defeat terrible serpents emerging from the earth.

Balmaint

Executioner for Sigfrei, the lord of Castle Kohan. That is until he must behead his former employer who is found guilty for a list of terrible crimes. Sigfrei’s last act is to give Balmaint a pendant and promises to be reborn seven times to teach the world of justice.

Arthur

Law clerk of Castle Kohan who ordered Sigrei’s execution. Travels with Balmaint when a man named Sigfrei appears in a neighboring region soon after the terrible lord’s very public execution.

Taria

A woman who eschewed the title of Arch Witch and dedicated her life to mastering the art of pottery. When her pottery takes on unnatural warping, she sets out into the world to discover the cause by pursuing a powerful fiery Spiritual known as the Phoenix.

Kahn

Until very recently he was an Imperial Guardsman of the grand city of Elhuacan. He gives all that up when he thinks of the wealth he and his mercenary band can obtain by joining with Taria in pursuit of the Phoenix.

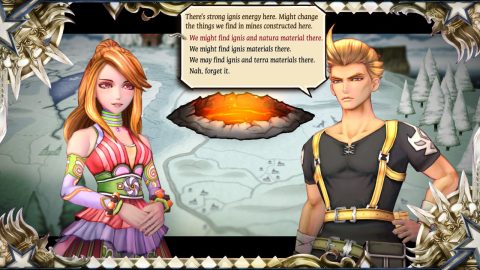

In regards to how you actually explore and traverse the world, Scarlet Grace is majorly stripped back compared to many other games in the SaGa series (except for Unlimited Saga which also attempted a more big-picture view of adventuring). Instead of smaller environments like towns or dungeons, the characters’ exploration will be kept entirely to the regional level. This involves choosing between spots that emerge from the map like you are opening pages of a pop-up book. As you explore these regions, their personalities and tribulations will be revealed, with the true story of the ancient fight between the Celestial and Infernal gods being told through modular and non-linear storytelling.

Without experiences like navigating a maze or other smaller environments, the game relies on other methods to explore and present choices. You might be using visual clues to chase down a gigantic land-bird, but before picking which bush the bird is hiding in, you see a gazelle seemingly turn to stone and drop down dead. Successfully finding the bird or not can actually leads to different positive outcomes, so long as you have the right puzzle pieces (or are even aware you have the puzzle pieces). This mode of thinking is radically different from most JRPGs, which can end up being very frustrating if you are not aware of what the breadcrumbs are. Even more frustrating, some event flags can conflict, preventing you from advancing one quest while another is occurring without any clear narrative reason or indication to the player.

While the stripped back quests can sometimes be overly terse or disjointed, much more successful is the combat system. In fact, Scarlet Grace makes a dramatic departure from previous games in the sheer amount of feedback and information it gives to players about how the game actually works. Unlike many turn-based games that keep the monsters’ actions a complete mystery, at the beginning of their turn players will know exactly what the enemies will do and the order everyone will act. This near perfect information ends up making player choices more meaningful.

Instead of choosing one action for each of your retinue members, you instead make use of a shared pool of action points (called BP in-game). You will often be using those abilities to move your character earlier and later in turn order, possibly defeating one enemy before they can act.

SaGa games often have strongly differentiated what weapons can do and in this installment they have their strongest identities yet. The techniques you’ll use with these weapons are not just for damaging enemies, they also will visibly move your characters forward and backward in the turn order, possibly positioning yourself to finish off an opponent before they can even act. Some techniques operate very quickly, moving the character near the beginning – like the bow users’ quick nock. Others can be more versatile, having options to go earlier or later – like the spear. Why would you want to go later in the timeline? Because of the game’s United Attacks mechanic.

The real benefit of moving your characters up and down in turn order is setting up United Attacks and preventing enemy ones. In addition to being the order of battle, that time line at the bottom of the screen is also like the positioning of your team relative to the enemy on a single axis. If you can surround and then eliminate that solitary goblin, your teammates smash together in a pincer attack to fill in the gap leading to a free hit and a BP discount on the next turn for all participants. This grants massive momentum to your team, opening up some of your strongest abilities with that BP discount on your next turn. Thus, isolating monsters on the enemy team and eliminating them on the same turn is the basic strategy you will aim for, requiring you to look for opportunities and flex your action choices to create those openings. Of course the player is also avoiding their own characters getting isolated and killed, as the enemy AI can also exploit United Attacks competently. This mechanic opens up a possible comeback play of goading the enemy to kill a weakened teammate (or allow them to die due to poisoning) that is right in the middle of two of your own allies, who can then retaliate with a United Attack and momentum swing of their own.

Other features of combat will also prove essential to success. A major departure from similar games is the diminished role of healing during battle. Healing is exclusive to magic and you will need to prepare healing one or more turns in advance. Often it is much better to prevent damage than it is to heal it later, because restoring HP as an emergency, reactionary move is not available after a bad turn. Magic always requires forward thinking as casters must chant for at least one full turn before a spell is unleashed. While experienced mages have the largest toolkits of any characters, novice mages can be tedious to foster in most circumstances. And we haven’t even talked about the status effect system which opens up even more options and ways for your team to work together, disable tough foes, or goad the enemy into inefficient turns. If you want your path to an efficient and satisfying victory to involve more than just damage numbers – and include plenty of meaningful decisions – this is a wonderful game to explore.

Stripped away of any extras, the designers focused on the element they were most passionate about: the combat. There are many choices here, but at the beginning of the game the implications of your decisions won’t truly reveal themselves until many hours later. Your hope is to have assembled a team that gives you the options you need when you tackle the toughest challenges. It feels amazing when you’ve assembled that working engine, but immensely frustrating when it feels like your team is fighting itself, never able to get into that perfect position when you need it.

While its strength in strategic and tactical gameplay is generally unchallenged, the game is certainly underdeveloped in many areas that the RPG audience takes for granted. While the game has many striking and beautiful art design choices, mostly seen in the grand mosaic featured in the introductory video, concept art, and backgrounds, there are many elements throughout the game that could more charitably be called raw or utilitarian but may more often be described as cheap. That some of the graphical effects such as transitions or world interactions seem like they never left the prototype stage or game-engine defaults reinforces this perception. Most information has to be conveyed through dialogue, which sometimes combines SaGa’s terse story telling with overly wordy establishing scenes. The 3D models for things like the enemies and character look good, but there aren’t very many of them and sometimes they need to play double duty such as spiders standing in for crabs or several palette swaps of NPCs and player characters. And of course the actual world keeps you at a distance, staying on the regional level as you travel across it. The towns themselves are a single image with one character acting as the representative for all the services and citizens in town. The Ambitions version of the game actually added a lot of general visual upgrades, animations, and voice acting in addition to additional superbosses, high-end weapons, and quality of life improvements such as vastly improved loading times.

While the game offers a lot of choices, it can sometimes be hard to understand what choices you are actually making, which seems to be an intended feeling. When outcomes are not obviously connected to player actions, things can feel arbitrary or random. Innocuous decisions will look indistinguishable from pathways that majorly impact your path through the game and it can be hard to guess what the game is trying to get you to notice.

The deviation from genre conventions is both its greatest weakness and its greatest asset. Its use of choice to change scenarios can take getting used to. And the dearth of clues for what possible outcomes might be can make failure states confusing. That said, there are both opportunities to fail forward while still having strict expectations on players. It is unlikely players will walk into a true dead end but knowing what mechanic to explore in order to dig yourself out of your troubles can feel paralyzing. As represented by the lightbulb of insight when sparking a new technique, knowledge is power in SaGa. This can sometimes mean the game is more fun on a replay than an initial play, as you can apply your knowledge in more situations and have much more context for the world – but you are enduring many frustrating moments to get there. Of course, typical to this entire series, that burst of inspiration and shock when you learn you can actually influence an outcome is a main part of the appeal.