- Wizardry (Series Introduction)

- Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord

- Wizardry: Knight of Diamonds

- Wizardry: Legacy of Llylgamyn

- Wizardry: Llylgamyn Trilogy Version Comparison

- Wizardry: The Return of Werdna

- Wizardry V: Heart of the Maelstrom

- Wizardry: Bane of the Cosmic Forge

- Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant

- Nemesis: The Wizardry Adventure

- Wizardry: Stones of Arnhem

- Wizardry 8

- Wizardry: Japanese Franchise Outlook

- Wizards & Warriors (2000)

- Wizardry Online

- Robert Woodhead (Interview)

- Wizardry Mobile Games & Other Media

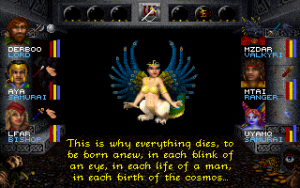

With Wizardry VII, Bradley emancipated the series even further from its Dungeons & Dragons-inspired roots. While the previous game already revealed the Cosmic Forge to be no magical relic, but a piece of ancient alien technology, the premise to Crusaders of the Dark Savant goes full-on SciFi: The party of heroes meets an android and is taken away in a space ship. Their new companion brings them to the planet of Guardia, which had long been concealed as the hiding place of the Astral Dominae, “the most powerful artifact of the universe”, created by a Cosmic Lord who goes by the rather undignified name Phoonzang. However, due to the loss of the Cosmic Forge, its location was somehow revealed to the galactic conqueror only known as Dark Savant, who seeks to use it to learn all the secrets of space, turning himself into a Cosmic Lord and gaining control over the entire universe. Even though they couldn’t hope to understand what is actually going on, the medieval fantasy heroes from Bane of the Cosmic Forge have to find and secure the Astral Dominae to protect it from the Dark Savant.

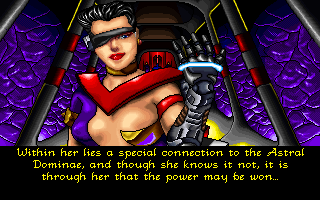

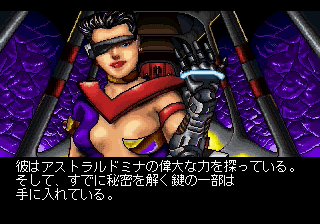

At least that is the story when starting a fresh game. After Return of Werdna and Heart of the Maelstrom had been standalone adventures, Wizardry VII once again allows to import a completed save from the previous game. Depending on the ending reached in Bane of the Cosmic Forge, the means by which the party travels to Guardia differ. They might instead get picked up by the Dark Savant, who tries to get them on board for his quest to end the tyranny of the Galactic Council. On his ship the party also meets the mysterious Vitalia Domina in person, a women wielding a power glove, who somehow is the key to reaching the Astral Dominae.

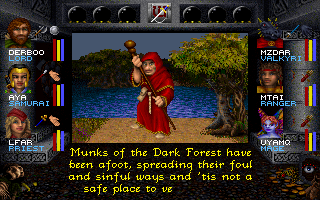

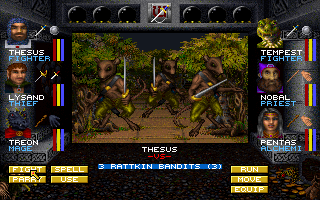

Once landed on Guardia – the starting location also depends upon the Wizardry VI ending – things look fairly medieval fantasy-like again, though. Most of the planet surface is covered by woods, with a few towns and dungeons in between. Aside from the robotic Savants, the planet is populated by a bunch of monks, the hoverbike-riding Helazoid amazon warriors, the Rattskins (nomen est omen) and the Gorns, who are totally not Orks and live in castle Orkogre, to make sure everyone perfectly understands that they are neither Orks, nor Ogres. But the center stage among the many peoples of Guardia is taken by the conflict between the two major spacefaring races, the humanoid rhinozeros race of the Umpani and the local dispatch of the arachnid-crustacean T’Rang Empire.

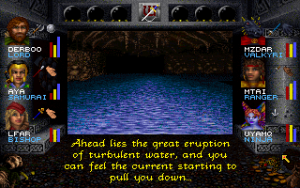

The rules have been adjusted a bit since Bane of the Cosmic Forge – some of the more useless skills have been removed, making way for replacements like swimming, climbing and the aforementioned map making. Both were only possible only at very specific locations in the previous game, but at least swimming has become a frequent required activity in Guardia. Unless this skill is very high, death through drowning is extremely common, so it’s about the most important new ability in the game. There are even a few special skills that can only be learned at certain locations during the quest. Skill points are no longer drawn from one common pool, either, but divided into weapon, physical and mental skills. The magic system remains mostly the same, albeit with a few added spells and the maximum casting level raised to seven.

Disarming treasure chests has been fundamentally changed. Instead of guessing letters, the character handling the trap now takes a guess about the configuration of a set of eight switches. Then the player scrolls through a list of traps and compares the recognized parts with them. Each trap has up to three buttons that need to be pressed in order to disarm, every other switch triggers it. The new method feels a lot more involved and more appropriate for a disarming process. Doors still work roughly the same as before, but things have been simplified: The game now automatically calculates the strength of the whole party to force open doors, and when unlocking, the thief gets to fiddle with each of the bolts individually instead of all at once.

Wizardry VII was widely considered as D.W. Bradley’s masterpiece and one of the crowning achievements from the era of classic turn-based CRPGs. It was also the largest Wizardry game until then by a wide margin, and no longer a mere dungeon crawler. The huge size comes also a bit to its detriment, though. The overworld is so enormous it’s almost impossible to properly map it. Apparently it’s possible to get by with 79 sheets of 20×30 grid paper when drawing the maps in the most economic way possible (that’s the amount of maps that accompany the most common walkthrough for the game). In a tiny hint of mercy, it is the first game in the series that originally featured an automap feature, although the party first has to find a map kit and train one of the members in the new map making skill. Looking at the map is quite inconvenient – it’s necessary to select the “use” item option, choose the correct character, scroll to the map kit and then activate it. It also only ever shows the close vicinity. To get an idea where the party is located in the world it’s necessary to compare with the rough overview map packed with the boxed release, which in turn doesn’t show any details.

The game is entirely non-linear, and upon landing the player doesn’t even get a clue what to do first. Even though most areas are effectively locked off due to being inhabited by far too strong monsters, the game is alway dominated by a crushing feeling of being lost. The world is full of items that absolutely have to be kept, remembered and recognized for puzzles somewhere at the other end of the world, dozens of gameplay hours later. Many puzzles aren’t necessary all that hard on their own, it’s just that the ingredients are spread out too far, and the hints are often obscure, if there are any hints at all. Example? When trying to get into a ruined town, the party finds the entry overgrown with trees. To get in, they have to find a grove a few dozen fields away, fight through an army of humanoid trees and plant a bonsai in the middle – which could be found in one of the earliest accessible dungeons, with no instructions what to do with it. Then the group can find a strangely grinning tree off the beaten path and apart from the main entry, which catapults them inside. And this is still one of the easiest tasks thanks to the consistent “tree” theme. All this is especially bothering with the strictly limited inventory. The game saves the locations of discarded items permanently, but once a crucial item has been left somewhere, it is practically impossible to find it again, so the player absolutely needs to decide on a storage location at a spot that’s easy to remember and easy to reach.

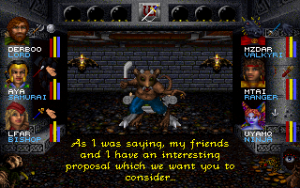

Furthermore, it is essential to take notes of every single task and piece of advice by NPCs. Quest logs hadn’t been invented yet, and sometimes the player is expected to remember entire phrases and type them in verbatim. A few of the NPCs also keep wandering around the world, and can only be vaguely tracked down by gathering news from other characters who might have heard of them. The moving characters even interact with each other, mostly by stealing valuable treasure maps, so their location is never secured, either.

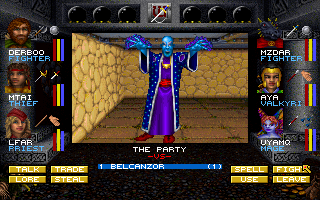

To make things even more confusing, Wizardry VII employs a complex diplomacy system. Allegiance is saved for factions as well as individual characters. When stepping into a faction’s settlement, the party might be welcomed or attacked on sight, depending on what actions they might have done or not done before, and the reasons are not always obvious. If the NPCs will at least engage in conversation, it’s possible to try and convince them with the diplomacy skill by trying to negotiate a truce, bribing or threatening the opposite party, but that is not always the case. The workings of the system are rather opaque, too. The party may try to talk wary NPCs into a peaceful transaction, upon which the game may give the message that the NPCs are pleased – immediately before they attack.

The game is also plagued by some shaky balancing. Bane of the Cosmic Forge had done away with the brutal permanent consequences from the original games, but Crusaders of the Dark Savant actually not only encourages, but often downright requires save scumming. A lot of trial and error is required, as there is no other way to find out if the party is suited for a particular area yet. Often the bosses, while looking nothing special, are a bit blown out of proportion in difficulty compared to the local regular enemies, and not seldom they can kill one or several party members in one single move. Usually the difference is just one or two levels per character, but from level 9 onwards that can take hours, especially when the inherited haphazard encounter rate happens to go way down for whatever reason. The difficulty of encounters is also completely random – a boss might face the party all on its own, or have several groups of powerful henchmen around, which can make a world of difference.

But regardless of all these issues, Wizardry VII cannot be called a “bad” game by any stretch of the imagination, in fact it’s really damn good. It’s full of interesting puzzles (some arbitrary BS notwithstanding), athmospheric writing and challenging quests. With the increased size also come some advantages, as this is the first game whose campaign truly warrants a thorough exploration of the complex job system, and not just by mindless grinding to max out the heroes before heading for the showdown. It just happens to be soul-crushingly huge and obtuse and intimidating. By any means, this is not the game to try and get into the series. The immediate predecessor is much better suited for that, despite its dire presentation. Although not quite as brutal as Wizardry IV, this is an expert course for the more battle-hardened RPG veterans. For those, however, it really is one of the best. From this perspective, suddenly the size of what essentially feels like one enormous dungeon becomes a strength, a host of seemingly unlimited opportunities for adventure.

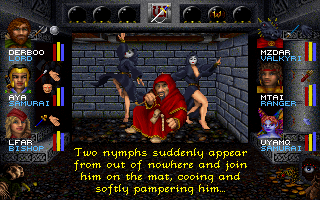

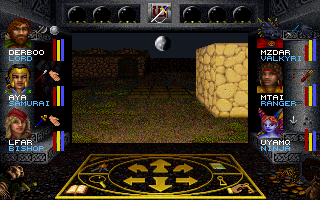

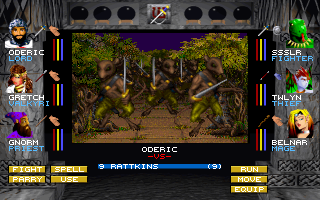

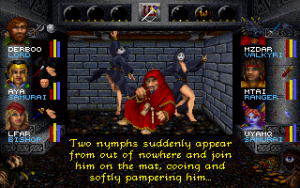

The graphics somewhat succeeded at catching up with the pack in 1992 (except for the groundbreaking Ultima Underworld), but they are still brought down by a lack of variety, mostly because almost all places in the world look the same. There are now a whooping four tile sets for the environments, but given the size of this game, each of them is seen just as much as the one dungeon wall in the PC version of Wizardry VI. Unique or special graphics are rare. There might be bitmap graphics for a computer here, a throne there or a contraption elsewhere, but stark dungeon walls and identical forest paths are the default for 99% of the game world. The same goes for NPCs, where the majority is still represented just by regular enemy sprites. Even among enemies, the artists have been miserly – so an “Earth Golem” looks exactly the same as the ent-like “Man O’ Groves”, and not even color changes are there to distinguish the mighty from the meek. The music is equally sparse – it’s a step up for the series that there even is music, but it is limited to the intro, the character management screen, and a jingle at the beginning of NPC interactions and fighting scenes. The latter is rather annoying, because it stops everything to a halt for the 2-3 seconds it plays each time.

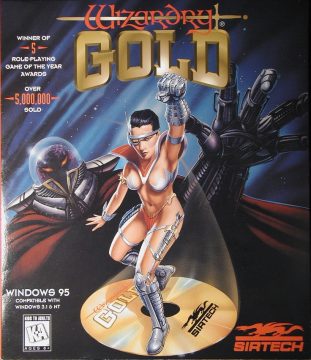

In 1996, Sir-Tech brushed up Crusaders of the Dark Savant for a new Windows release, titled Wizardry Gold. Most of all, this turned out to be a quest to make the game uglier. It got a new ugly render interface, new ugly character portraits that look much too cartoonish compared to the rest of the game, and ugly FMV variants of the gorgeous pixel art cutscenes with lots of artefacting and the backgrounds replaced by ugly prerendered scenes. Everything is displayed in 640×400 pixels resolution (always windowed), but the 3D windows is simply upscaled and filtered. This works OK for the characters, but not so much for the environments. It also comes with a bunch of bugs, most notably the diplomacy system being broken/deactivated. The only thing the Gold release really adds to the game is narrated voice over for much of the text. The voice acting is not as terrible as things could get back in the mid-1990s, but it’s not exactly stellar work either. The music was also replaced, but it’s still just a couple of jingles, and it sounds just terrible. Wizardry Gold was also published in Korea, where the local box was an odd anomaly – the scantily-clad Vitalia on the cover was photoshopped to remove her vaguely Asian-looking features.

The Saturn version has the same polygon engine, annoying menu navigation and load times as its bundled predecessor. The enemy graphics and character portraits, on the other hand, remain identical to the DOS version this time. It has much better music than Wizardry Gold, but no voice over. The cut scenes are also the same as the original, but still presented in ugly, lossy FMV sequences. The PlayStation version by Soliton – actually the company’s first Wizardry port before Legacy of Llylgamyn – released with the subtitle Guardia no Hōju (“Jewel of Guardia”) has much better looking 3D environments, but uses anime style character portraits and pre-rendered graphics for the monsters and cutscenes. While the game itself uses text only, it has a voiced intro, which curiously is in English but does not use the same recording as Wizardry Gold. It isn’t any better, though.

Comparison Screenshots