Astrocounter of Crescents, a 1996 mecha beat-em-up from Korea, is many things. It’s heralded as a hallmark of the ‘90s Korean gaming scene, thanks to its remarkable production value for the time. Numerous Korean developers around this era opted to mimic the games outside of the home country, but Astrocounter of Crescents was one of the few that truly stood out among its peers, having all the ingredients to potentially become a classic that comes close to, even challenges, the Japanese action games that inspired it. It’s not hard to see how it enamored the public – this game features hardcore mecha action, bombastic visuals, and awesome CD music, all wrapped in a melodramatic heroine’s tale.

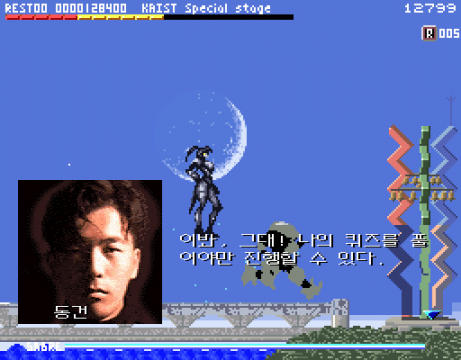

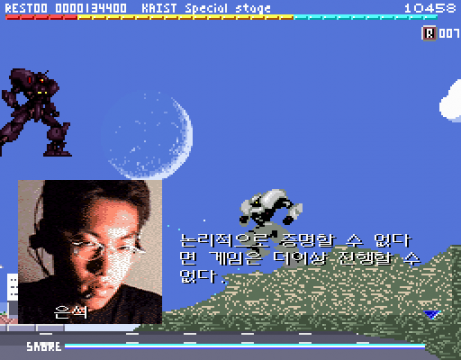

Part of its cult favorite status can be attributed to the game’s unusual pedigree. Although it was published by Samsung and its developer is credited to an obscure company known as S&T On-Line, a large bulk of creation was handed over to Object Square, a short-lived development house consisting of two then college students, Kim Dong-gun and Yi Eunseok. This was their first and only commercial release, besides a couple of freewares (which will be touched on later in this article). Both later wound up joining Nexon following its dissolution, and formed the core team of devCAT studio, responsible for the big hits like Mabinogi and Vindictus.

Set in the year 2095, Astrocounter of Crescents paints a dystopian future where the world is ravaged by constant conflict between the union of space colonies and the resistance group that opposes it. Making things worse, malevolent corporations are capitalizing on the situation by lobbying them to bank on their technology, most notably the weaponized power armor Astrocounter (abbv. Asca). Neurocraft is one of them, wishing to monopolize the market over the solar system via their newest prototype Asca unit, Bulgidung.

Set in the year 2095, Astrocounter of Crescents paints a dystopian future where the world is ravaged by constant conflict between the union of space colonies and the resistance group that opposes it. Making things worse, malevolent corporations are capitalizing on the situation by lobbying them to bank on their technology, most notably the weaponized power armor Astrocounter (abbv. Asca). Neurocraft is one of them, wishing to monopolize the market over the solar system via their newest prototype Asca unit, Bulgidung.

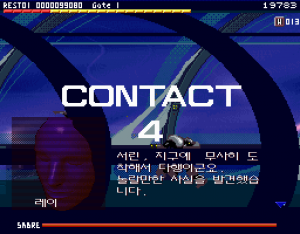

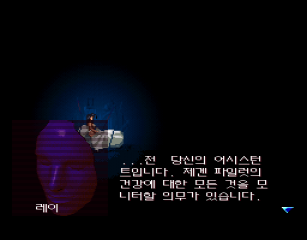

The plot focuses on Seo Lin, Bulgidung’s test pilot, who has been haunted by a nightmare that implies her personal history with Neurocraft. One day, her facility is stormed by unknown forces that commence a ruthless onslaught, leaving Lin as a sole survivor. Just as distraught over her colleague’s demise, Lin soon finds herself in a predicament: Neurocraft has pulled the rug out on her, framing her as a prime suspect working for the resistance and ordering the union military to exterminate her and Bulgidung by all means. Realizing she’s fallen into a farce, Lin starts a lone mission to clear her name, fighting her way through factions she once worked for and uncovering her connection to the corporation.

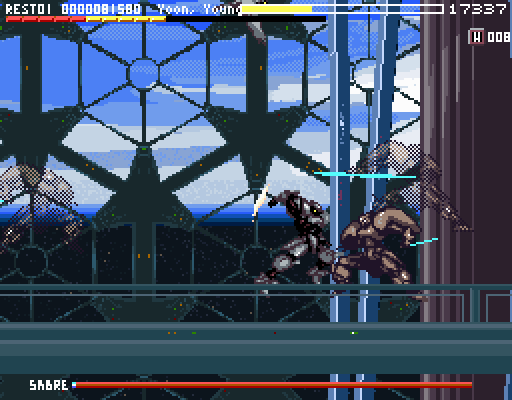

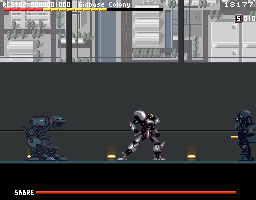

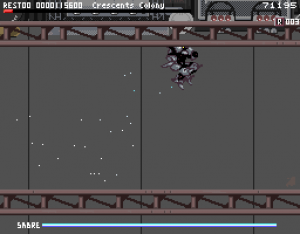

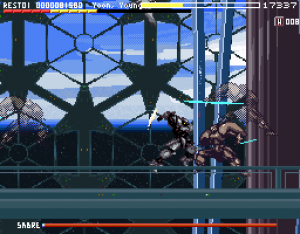

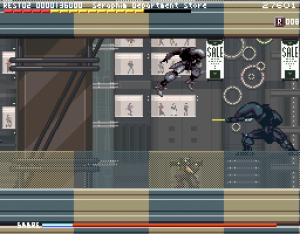

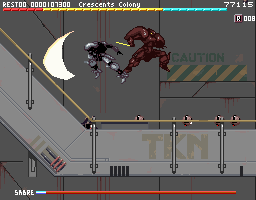

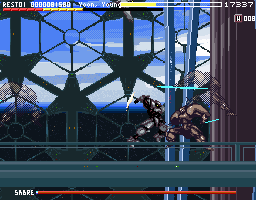

Astrocounter of Crescents is a single-plane beat-em-up with a total of nine stages, each again broken down to several sections. Bulgidung relies on melee combat, using one attack button (Ctrl) for your sabre, one for your sub-weapon (Alt), and the direction keys for movement, of which jumping is done by pressing up. For a game that came out in 1996, the game has surprisingly arcade-y design, having no RPG elements or other gimmicks to pad out the action. The levels themselves rarely deviate from a linear path filled with various foes.

Astrocounter of Crescents is a single-plane beat-em-up with a total of nine stages, each again broken down to several sections. Bulgidung relies on melee combat, using one attack button (Ctrl) for your sabre, one for your sub-weapon (Alt), and the direction keys for movement, of which jumping is done by pressing up. For a game that came out in 1996, the game has surprisingly arcade-y design, having no RPG elements or other gimmicks to pad out the action. The levels themselves rarely deviate from a linear path filled with various foes.

This sounds all great on paper if you prefer old-school beat-em-up’s simplicity, but the execution is questionable, starting with its strange controls. If anything, Lin’s Bulgidung moves less like a typical mecha robot and more like the Belmonts from the Castlevania series. It has great mobility but is unable to adjust its momentum once its feet leave the ground, forcing you to time your jump with extra caution (thankfully, this game is devoid of bottomless pits or any sort of complex platforming).

Your sabre also has aggravatingly long-winded animation, which can be fatal when it misses your target. To surmount this, you have to chain all of your available moves into each other, by cancelling them through either ducking or jumping out in middle of performing them. This can be abused to great extent, as you can continuously strike your foe while alternating between standing and squatting. If you ignore this and simply keep pressing the attack button like an ordinary beat-em-up, the controls will feel stiff and refuse to cooperate at worst moments.

The awkward control scheme takes some time to get used to, and it doesn’t help that essential gameplay mechanics are hidden to the player, unless you can understand Korean and read them up at (now defunct) official website or the game’s manual. Holding an attack button charges the Sabre meter at the bottom of the screen. Once it maxes out, you can release the button to unleash a stronger blow that has longer reach, but taking damage will reset the meter. Every defeated enemy drops a spread of small capsules called Cells; these are used as ammo for your sub-weapon, but their real potential lies in temporarily boosting your sabre. Hit your opponent with a Cell in-between, and your Sabre meter instantly charges up, performing it as your follow-up. Do the same with fully charged sabre, and you can execute a special move called Double Smash that causes even more damage. You can also block all and any attack aimed at you by promptly moving away from it; pressing the attack button again at this point will let you counter.

The awkward control scheme takes some time to get used to, and it doesn’t help that essential gameplay mechanics are hidden to the player, unless you can understand Korean and read them up at (now defunct) official website or the game’s manual. Holding an attack button charges the Sabre meter at the bottom of the screen. Once it maxes out, you can release the button to unleash a stronger blow that has longer reach, but taking damage will reset the meter. Every defeated enemy drops a spread of small capsules called Cells; these are used as ammo for your sub-weapon, but their real potential lies in temporarily boosting your sabre. Hit your opponent with a Cell in-between, and your Sabre meter instantly charges up, performing it as your follow-up. Do the same with fully charged sabre, and you can execute a special move called Double Smash that causes even more damage. You can also block all and any attack aimed at you by promptly moving away from it; pressing the attack button again at this point will let you counter.

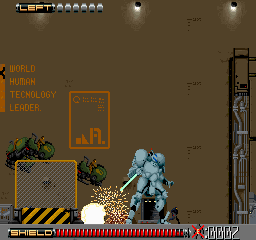

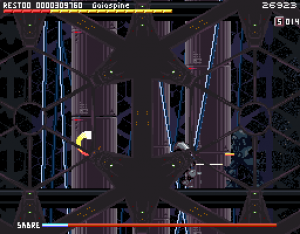

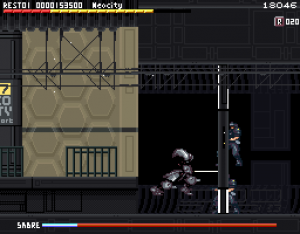

Mastering these tactics will definitely increase your chance of survival, but nevertheless, Astrocounter of Crescents is an extraordinarily unforgiving game. Enemies are sturdy and agile, their erratic pattern hard to read, but the real danger are those with projectile arsenal, as there’s no invincibility period after taking damage, at all. Fail to avoid a barrage of bullets flying at you, and your seemingly extensive health bar will get emptied in a matter of seconds. The game allows unlimited continues, and death sends you back to the beginning of the section (or in case of boss fights, a rematch), but losing all your lives means restarting the level all over, which can be major setback in some of the longer ones.

There’re a lot of things that can kill you immediately, like the annoying anti-mecha mines found in the first few levels. The early half is relatively docile, being short enough to overlook rough edges, but it’s the fifth stage that difficulty ramps up off the chart. This stage requires you to make your way through a thick brigade of army, an extremely tight run-away-from-train sequence, and the battle against a trio of cyborg riot police at the end. This wouldn’t have been so bad if it didn’t just happen to be the first level without any checkpoint, meaning you need to complete it in a single life, not to mention the ridiculously short time limit. The rest of the game never lets up from here on, and eventually it becomes all but impossible to make any progress without exploiting every single bug in the game.

To balance things out, the game hosts a collection of upgrades that adds additional bars to your health meter, as well as a selective type of sub-weapons casted from your Cells. Many of these (Counter Barrier, Plasma Shocker, Unit Bomb, Smasher) are short-ranged secondary firearms, but others serve more peculiar purpose, like Repair, which replenishes your health, or Throw Cell, which spawns one of the Cells in front of you (combined with Double Smash, this can be a game-breaker with trained hands). There’s also Wing, which calls a robot hawk that homes to nearby target a la Mega Man 5‘s Beat.

To balance things out, the game hosts a collection of upgrades that adds additional bars to your health meter, as well as a selective type of sub-weapons casted from your Cells. Many of these (Counter Barrier, Plasma Shocker, Unit Bomb, Smasher) are short-ranged secondary firearms, but others serve more peculiar purpose, like Repair, which replenishes your health, or Throw Cell, which spawns one of the Cells in front of you (combined with Double Smash, this can be a game-breaker with trained hands). There’s also Wing, which calls a robot hawk that homes to nearby target a la Mega Man 5‘s Beat.

This is a good comeback mechanic that however goes less useful than it intended, mainly because of two reasons. One, these items are only dropped by predetermined foes who look no different from the others, so you’ll never know where you can find them until you’ve replayed the stages enough times to study them in and out, a tedious task in an already tough game. Secondly, most of the sub-weapons either spend so much ammunition or have little practical use that their inclusion seems almost pointless, a problem accentuated by that you can accidently pick these up, as they’re too small to spot in middle of fighting or when they’re obscured behind foregrounds. If you want to hold on Repair or Throw Cell, two of the most useful perks in this game, you’d better watch out not collecting any others for the remainder of the game, as some stages don’t have them at all (including the very final level).

All of these factors contribute to putting you into a situation where fighting isn’t just worth the headache it entails. Indeed, in later levels, it’s often for the best to avoid engaging battle altogether, only decapitating a few that grant health restoratives, and zoom through the stage as unscathed as possible, because there’re way too many enemies squeezed into one place that can and will massacre you on the spot. That’s a shame, as the combat is fun as ever when it’s tilting to your favor. It’s just that the game seems confused about drawing a line between “challenging” and “unfair”.

All of these factors contribute to putting you into a situation where fighting isn’t just worth the headache it entails. Indeed, in later levels, it’s often for the best to avoid engaging battle altogether, only decapitating a few that grant health restoratives, and zoom through the stage as unscathed as possible, because there’re way too many enemies squeezed into one place that can and will massacre you on the spot. That’s a shame, as the combat is fun as ever when it’s tilting to your favor. It’s just that the game seems confused about drawing a line between “challenging” and “unfair”.

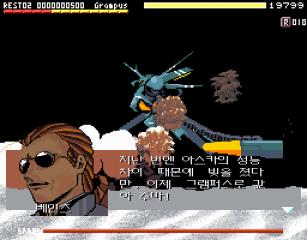

The boss fights tend to be more compelling, often requiring you to figure out specific strategy that can damage them (sometimes an intervening transmission will teach you their weak points). There’s one boss you can inflict only by countering their move, which’ll definitely put your skill into test. These aren’t without their own issues, though. Some of them can easily crush you to death because of shoddy hit detection skewed against the player, while others have such a cheap attack pattern that is incredibly hard to dodge, rendering their encounter a matter of blind luck.

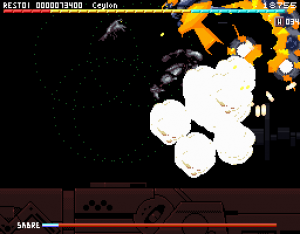

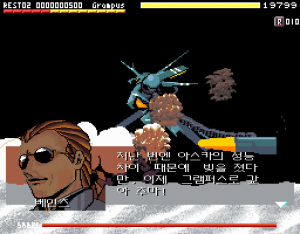

Even in its lowest moments, Astrocounter of Crescents delivers consistently on visual pizzazz. While the game technically runs in SVGA mode, the actual gameplay screen estate is comprised of 256×200 pixels, with only character portraits and fonts displayed in higher resolution. Nevertheless, the spritework is ace, showing off fancy programming tricks that recall Treasure games (including their trademark multi-segmented boss). There isn’t much variation in level theme, mostly set in night or dim interior, but its muted gray palette suits the gritty, somber nature of the game. The enemy mechas have stylish design, and everything Bulgidung slashes through makes a striking explosion littered with abstract particles (though reportedly, there were complaints that its excessive special effects caused ungodly amount of slowdown in underpowered hardwares).

Even in its lowest moments, Astrocounter of Crescents delivers consistently on visual pizzazz. While the game technically runs in SVGA mode, the actual gameplay screen estate is comprised of 256×200 pixels, with only character portraits and fonts displayed in higher resolution. Nevertheless, the spritework is ace, showing off fancy programming tricks that recall Treasure games (including their trademark multi-segmented boss). There isn’t much variation in level theme, mostly set in night or dim interior, but its muted gray palette suits the gritty, somber nature of the game. The enemy mechas have stylish design, and everything Bulgidung slashes through makes a striking explosion littered with abstract particles (though reportedly, there were complaints that its excessive special effects caused ungodly amount of slowdown in underpowered hardwares).

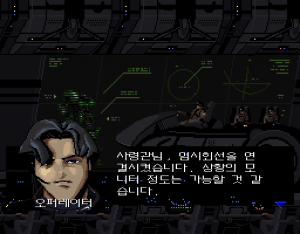

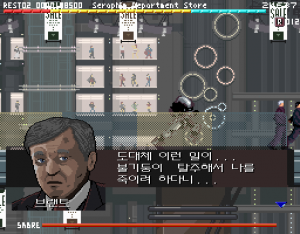

One of the game’s biggest draws would be its story. There’re a lot of cutscenes, both between and within levels, and further supplementary material is available in the game’s manual to fill the gap about its world. The downside is that the sheer amount of textboxes gets quickly annoying, and you’re forced to watch them all over again upon continuing. Still, while it relies on all kinds of sci-fi tropes – quest for identity, megacorp conspiracy, musings on human nature, and a number of character deaths – the writing does live up to the box cover’s poignant tagline (“A human being lives as a tool for another.”). The ending is strikingly bleak, having those pulling the string get away scot-free and leaving Lin in a certain doom. The scenario was penned by Lee Weon, who’d also end up working in joint with devCAT and write for early Mabinogi campaigns.

The soundtrack was supplemented by Kwak Dong-il and Kwon Guhee from SoundTeMP, the famed musician group behind Korean MMORPGs such as Talesweaver and Ragnarok Online. SoundTeMP had worked on various DOS games around this time, but this is one of the first works they took advantage of redbook audio. Leaning toward heavy electronica and house music, it oozes the rocking atmosphere of the Japanese PC Engine CD games, and for most Korean audience who probably weren’t too familiar with CD-ROM format console titles, this would’ve been a real treat.

The soundtrack was supplemented by Kwak Dong-il and Kwon Guhee from SoundTeMP, the famed musician group behind Korean MMORPGs such as Talesweaver and Ragnarok Online. SoundTeMP had worked on various DOS games around this time, but this is one of the first works they took advantage of redbook audio. Leaning toward heavy electronica and house music, it oozes the rocking atmosphere of the Japanese PC Engine CD games, and for most Korean audience who probably weren’t too familiar with CD-ROM format console titles, this would’ve been a real treat.

The game may have been indirectly inspired by Genocide 2, a Japanese 2D mecha beat-em-up that lets you control a humonoid mecha built around melee combat. There’re more than a few coincidences that reinforce this theory; the contemporary IBM PC port of Genocide 2 was released exclusively in South Korea one year prior, developed by Mantra (the creator behind Ys II Special remake). Even this port’s soundtrack was redone by SoundTeMP themselves! There’re enough differences between the two that it can’t be exactly treated as a rip-off, but one can’t still help but question if this particular game had some influence on Object Square’s brainchild in some ways.

There’s an amusing anecdote regarding the game’s publication. In the original release, there was a secret feature that if you eject the disc during the gameplay, it’ll play a voice message from one of the developers that roughly translates to: “Shut your drive, asshole!” This was supposed to be a prank to surprise their fellow programmer, but it slipped into the final product by mistake, which got immediately caught on media and prompted Samsung to re-print the copies to remove said profanity. This “easter egg” version has since become a collector’s item, asking for even higher price than regular packages.

Unfortunately, the game is notorious for having tons of performance issues on modern system. It has poor compatibility with emulators like DOSBox and is prone to random crash, a death knell to a game that doesn’t have any method of saving. Without proper configuration, it’ll suffer from obnoxious audio corruption, constant stuttering, and a variety of graphical glitches. It was never re-released on Windows or ported to other platforms, and resurfaced only one time in 2002 as a cellphone app by Mobile Nature (which also resurrected a few other Korean DOS games). There’s not enough information left on internet to confirm whether this is a simplified conversion of the original game or something else entirely.

Astrocounter of Crescents is an unique title with a lot good going for it, but nowadays it’s just a difficult game to go back to. Any obscurity enthusiast might buy it from heart, but those who came expecting a no-brainer action game are gonna get frustrated by its sloppy design; it has a few too many hurdles to overcome (cumbersome controls, relentless difficulty, and other assortment of quirks that punish uninitiated players) to appreciate in this day and age. If you’re willing to give it a chance, an English fan translation was released in 2014, ensuring overseas fans may find some enjoyment out of it.

Related Games – 85 Doe-eot-suda! (1994) / Sakje Doe-eot-suda! (1997)

During the first section of Stage 8, there’s a secret path leading to a wacky hidden level, where the Object Sqaure developers turn up to mess with Seo Lin. This level borrows the graphics from their earlier game, 85 Doe-eot-suda! (85되었수다!), a freeware shoot-em-up intended as a homage to the international hit Gradius series. The name itself is a double pun title; when read out loud it sounds almost like Parodius Da!, the second game in Konami’s own spoof series, but it also translates to “I Became 85”, referring to the game’s over-the-hill hero Doctor Hal. In the opening that parodies the MSX Gradius 2, he’s dragged out of retirement into a war against Dr. Salmosa (this game’s Dr. Venom), joined by his granddaughter Sanso (the player 2).

85 Doe-eot-suda! was distributed through BBS in 1994 as a proof-of-concept public demo containing one stage, but the development was put on indefinite halt as the source code was lost in an accident. It wasn’t until 1997, after completing Astrocounter of Crescents, that it saw a revival for special contest. Held by an amateur developer group known as Hi-Tel Game Making Association, it accepted any sort of video game with only one rule: its size had to be under 100KB. Object Square dug out leftover assets for this competition, and retooled them into a quasi-sequel known as Sakje Doe-eot-suda (삭제되었수다!), this time meaning “I Became Deleted”.

Sakje Doe-eot-suda!

Despite all the compromise it suffered to make the cut, Sakje tries to make it up for its sense of humor. This version has a revised intro that chronicles rocky production of the previous game, one of pictures showing the developer’s computer torching up into fire. There’s now constant dialogue between the characters, including Object Square team themselves, throwing all kinds of excuse to remove a feature to cram the game. One of them threatens to give you an instant Game Over if you destroy his personal monitor (that somehow ended up in this game as Dr. Salmosa’s last resort), and he’s not kidding. The best laughs come from the new bosses, one of which is a title logo repurposed into a battleship. Lin’s Bulgidung also makes a brief cameo. All in all, both games are far from the most inspired Gradius fan games out there, but it’s an intriguing novelty nonetheless.

Links & Further Reading:

- Official Homepage (via Internet Archive)

- derboo’s Translation Page – The English fan translation patch and some background information nabbed from official website above. Mirror download link available at Romhacking.net.

- Astrocounter of Crescents Soundtrack on YouTube

- Kim Dong-gun’s entry in Naver Encyclopedia (in Korean) – More details about Kim’s career while working in Object Square.

- This Is Game‘s 2019 interview with Lee Weon (in Korean) – An article discussing Lee’s contribution to this game and Mabinogi, and their influence over his later works.