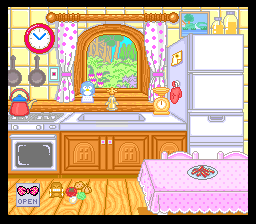

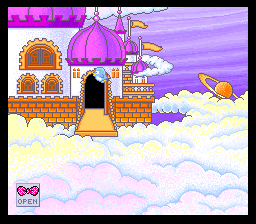

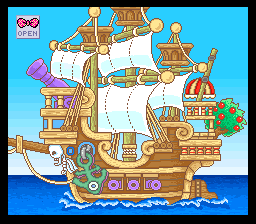

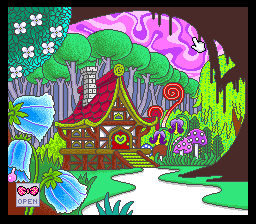

From the very moment you boot up the game, it’s clear what Motoko-Chan no Wonder Kitchen is. Its visual style is a dead giveaway: the marketably cute mascot, the soft pastels, the round, non-threatening font, even the sheared edges on the sides of the pink box. They all combine to form the label on a product you can easily imagine spotting on the shelves at your local grocery store. Of course, that’s exactly what the game is, but the creative decisions within the game itself make it obvious the extent to which that informed the game’s design.

A Cooking Mama-esque title with at least some involvement from Nintendo during its development, Motoko-Chan no Wonder Kitchen belongs to a strange category of tie-in games. Much like Chex Quest and the Burger King games, Motoko-Chan was included with the product it was advertising (in this case, Ajinomoto brand mayonnaise). And much like any other game based on a pre-existing brand, Motoko-Chan is aware of the purpose built into it: to promote the brand it’s associated with. Where it starts to break away from its peers is in its failings. Motoko-Chan‘s main flaw isn’t that it’s flat or that it fails to justify its existence outside being a piece of promotional material. In fact, the game makes unexpected efforts to avert such a catastrophe. Yet in doing so, it plunges itself into needless self-conflict and can’t find the resolution it needs to get out.

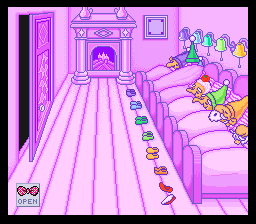

Much of that conflict comes from how the game plays. Despite initial impressions, cooking only comprises a very minor portion of the game. The rest borrows more heavily from contemporary adventure games: you move your mouse cursor about static environments, solving basic logic puzzles and clicking on every object in sight in the hopes that one of them gives you whatever you need to advance through the game. The only difference here is the absence of logic. Motoko-Chan is an emphatic rejection of everything that adventure games stand for. Anybody who’s played an adventure game can tell you how teleological the genre is. You enter these games with the assured belief that everything follows an internally consistent logic; that every object you find has its purpose. Even you, the player, have a role to fulfill: discern the world’s logic and push through to the end.

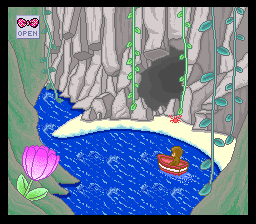

Motoko-Chan, on the other hand, feels nothing like this. If anything, playing the game feels like taking a journey to Wackyland, where at any place and at any time, you may find yourself bombarded by some nonsensical gag. You click a plate of sausages, only to see each one transform into one of the seven dwarves. They perform a dance, steal your food, transform into a shooting star, and then whisk themselves away to god knows where. What just happened? Try as you might to make sense of the situation (or anything else the game has to offer), you’re simply not equipped to do so. The basic laws of cause and effect mean nothing in a world that eschews both. And with the game’s internal logic frantically switching based on the designers’ impenetrable whims, you can’t even be sure what the hell the game is, much less accept it for what it is. So depending on how you interpret it, Motoko-Chan could be either a series of one-off Looney Tunes bits or an absurdist take on adventure game sensibilities.

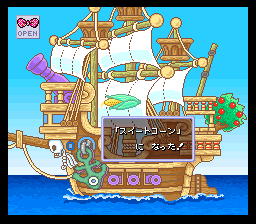

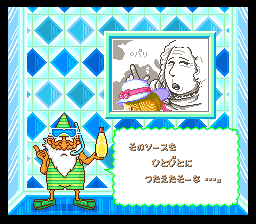

Unfortunately, generous readings like this don’t hold up to further scrutiny. Despite its pretensions at meaninglessness, the game is built to serve a discrete purpose: to promote awareness of Ajinomoto mayonnaise. Even putting aside any knowledge tied to the game’s distribution (IE that it was given away only to loyal Ajinomoto customers), Motoko-Chan itself is all too eager to make that knowledge relevant within the game itself. What few distinct characters there are use any opportunity they can to advertise the product, and the overarching plot at least tries to relate itself to this purpose by centering your adventures around gathering the missing ingredients for three mayo-based recipes. In doing so, Motoko-Chan forces us to interpret it not as a surreal adventure, but through this readymade lens, and it’s along these lines that the game fails. Far from being endearing, the numerous gags only distract from the game’s purpose while offering nothing in return. It doesn’t help that the game makes only the barest effort to relate any of them back to cooking.

At this point, you’re left wondering who the game is even made for. Is a find-it book made for children? If that were true, then the mayonnaise lessons and the cooking segments would surely turn them away. (This isn’t even getting into the dangers of encouraging small children to use knives, ovens, boiling water, etc.) The game can’t be for adults, either, since even at the time, there would have been far better sources of cooking advice than a promotional video game. Motoko-Chan is left confused, struggling for an identity.

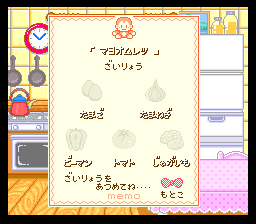

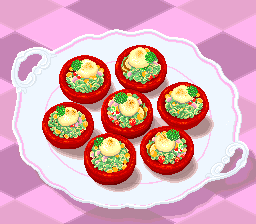

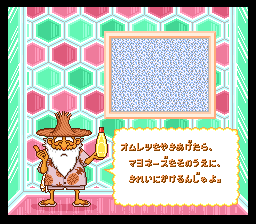

Yet even if you were to put all that aside, the game would still be riddled with severe problems. It’s all thanks to the cooking element. As informative as the mayonnaise lessons can be, the recipes that follow are paradoxically unhelpful. On the one hand, they’re too vague. Rarely will the game specify even the most basic facts one would need to prepare these dishes, like times or amounts or serving sizes or anything outside the step-by-step instructions it does offer. (It’s not that the game is unaware of how these influence the cooking process. For whatever reason, it doesn’t care to explore them.) Yet on the other hand, the recipes are also so specific as to be redundant. It’s not uncommon to add salt/pepper to a dish at one point while preparing your dish only to add it again at another point down the road. The game never explains why. Were you to follow its instructions, you would easily end up with either crispy black tomato bowls or runny omelettes that taste like salt water.

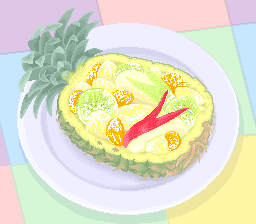

And mayo. Motoko-Chan will slather anything in mayo. In fact, it loses any semblance of self-control the moment mayo enters the picture (which it inevitably will). Fruit salad probably wouldn’t benefit from more mayo, and it’s hard to take the game seriously when it claims that the sauce is a key ingredient in almond sauce. But it doesn’t care. So long as it can relate these dishes to mayonnaise somehow, it’s going to the stuff up. The recipes reach their peak absurdity when the game instructs you to add mayonnaise (an egg-based product) to your omelette (another egg-based product). So in addition to being potentially unappetizing, Motoko-Chan‘s dishes also run the risk of being potentially unhealthy.

The best thing to be said of Motoko-Chan no Wonder Kitchen is that its art is whimsical and fun. At best, such a defense sidesteps the problems that persist within the game, and at worst, it would turn one’s gaze back toward them. However, it may yet be the game’s last hope, for without that defense, Motoko-Chan has little else to fall back on. It has neither the charm nor the culinary acumen of Cooking Mama, nor is it conducive to the ironic appreciation that other brand-centric games lend themselves to. Even the purpose for which the game was ostensibly made – to advertise the Ajinomoto brand – consigns the game itself to irrelevance. Mailing in two proofs of purchase in exchange for the game already shows the company that you’re aware of them. So once again, Motoko-Chan must contend with a question it ultimately can’t answer: what is it?