This game is featured in our digest, Namco Arcade Classics! Please check it out!

Namco released three side-scrollers in the arcades in 1988. Bravoman (or Beraboh-man) was a hit in Japan, and spawned a shoot-’em-up spin-off; Splatterhouse was a hit in America, and turned into a series. Both games were ported to NEC’s Turbografx-16, and have been re-released on multiple occasions.

Mirai Ninja (“future ninja”), meanwhile, was not a hit anywhere, and never received a console port or re-release. This is all the more ironic when you consider that it was the most ambitious of the three. Not only was it the only one to use Namco’s new System 2 arcade board, it was also one half of what the Japanese term a “mixed-media” project, meaning, in that case, that a live action film was developed concurrently with the game, so that both could support each other commercially on release.

Key to this project was Keita Amemiya, a cult figure of the Japanese entertainment industry. A television and film director, character designer, illustrator, and writer, he’s worked on the biggest tokusatsu franchises (Kamen Rider, Super Sentai, Ultraman), before creating his own (Garo); written & directed several movies, including the early ’90s sci-fi cult classic Zeiram, which itself birthed a small franchise; authored a fantasy horror novel and some manga; and contributed to over a dozen video games, including Onimusha 2, the Genki duology and Shin Megami Tensei IV. By 1988, however, his most notable contribution to video games had been the cover art for the Famicom Disk System Zelda-clone Seiken Psycho Calibur, and he had yet to direct anything.

Amemiya had been working as a character designer on Toei’s superhero series for just two years when he was hired by Namco to provide designs for an arcade game they were developing. According to a 1997 book about the tokusatsu genre, he became so taken with the characters and setting that he personally convinced Namco’s top executives to produce a movie based on them, though they had never done such a thing before. While he initially intended for an acquaintance at Namco to direct it, he ultimately ended up with the job.

The actors were either beginners or bit players. One of the leads had appeared in Akira Kurosawa’s Ran, along with two Juzo Itami comedies, in roles so small they didn’t warrant names; another had decades of experience playing bad guys who’re lucky to get a few words in before they get killed. Unsurprisingly, the performances turned out uneven. The better ones are theatrical, in the style of TV samurai dramas; the weaker ones are wooden or unsteady.

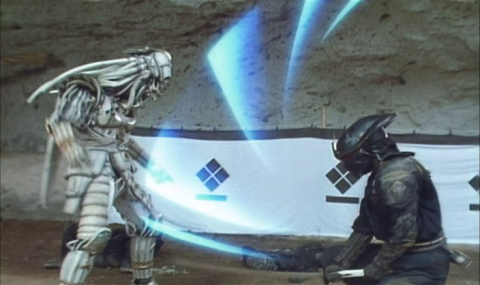

The special effects are of the old-fashioned, practical type that comes off as charming to fans of old sci-fi and ridiculous to most people. Low-level mooks wear goofy costumes and walk funny like the Putties in Power Rangers, while the top villains look like characters from some demented stage play.

Wild costume, but the actor’s pretty good.

The sword-fighting choreographies aren’t bad at all, and the stuntmen are game enough, throwing themselves up and down dirt hills as they get cut down, blown up and shot. At one point, a soldier launches into a front flip from the impact of an explosion before breaking his back on a large rock. Hopefully, that crag is just a prop; it looks painful either way.

AAAAARGH

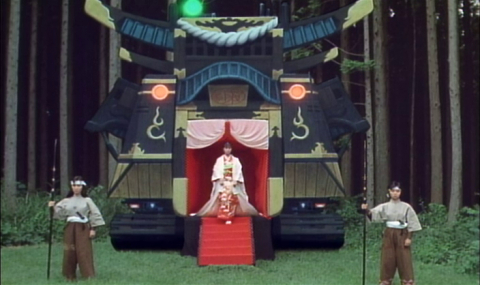

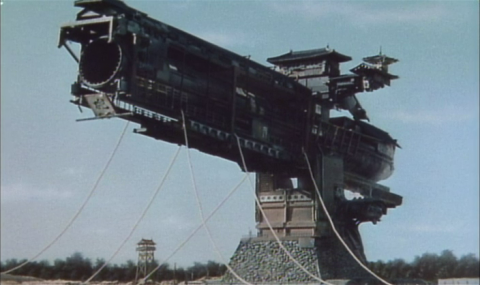

The first line of the opening narration suggests that the movie takes place in the distant past and the future simultaneously, which is a fair if nonsensical summation of the general aesthetics. There are giant, Star Wars-style walker robots, automated tanks with parts that look like traditional Japanese castles, and samurai warriors who wear electronic devices displaying their ki level on the side of their heads like reverse Dragon Ball Z visors. The good guys use wood-and-metal rifles that fire lasers out of cannons shaped like Gatling guns, or swords whose handles can be loaded up with spirit bullets for extra power. The bad guys are mostly robots. It’s Ancient Japan and it’s the future all at once.

The princess exiting her tank/traveling private chambers.

In this world, the remnants of the Suwabeh, a samurai clan nearly destroyed in an earlier battle with the Dark Overlord’s troops, are getting ready to try out their new weapon, an enormous, pistol-shaped cannon they hope will be powerful enough to destroy the enemy’s castle. Unfortunately, their princess-in-hiding is taken prisoner on her way to witness the event. A grizzled mercenary named Akagi proposes to infiltrate the castle with a small group of soldiers and rescue her before the coming eclipse, at which point he insists the weapon must be fired whether they have made it out or not or some catastrophe will occur.

The gun-cannon in question.

This is because the Dark Overlord’s troops have been feeding their master human souls in order to bring him back to life, and the time of resurrection is near. But Akagi and his group aren’t alone in trying to stop them; Shiranui, the future ninja, is there too. He’s a bit of a Robocop type; a former Suwabeh warrior whose conscience was transferred into a cybernetic body as he was dying, he’s fighting to recover his soul, which his enemy has snatched and stored away. Eventually, Shiranui joins Akagi and the lone surviving soldier, Taromaru, and the stage is set for the final battle.

Technically the next-to-last battle.

At just 72 minutes, the pacing almost can’t help but be tight, and with an intriguing world, decent script, and slightly above-average martial arts, it’s all surprisingly watchable, even with the cheap special effects and costumes.

The movie ended up being released directly on VHS just a year before the Original Video boom would create a market for such things in Japan, and doesn’t seem to have made much of an impact. In America, it was picked up by the famous / infamous Carl Macek’s Streamline Pictures, slapped with a cheap dub, and renamed Cyber Ninja. Thankfully, today it is possible to watch it with English subtitles, which is easily the better option.

Meanwhile, the game’s development incurred delays, so that it ended up being released a few months after the movie. We don’t know who designed it; as was often the case then, many of the core team members were credited under pseudonyms, and its main creator is unknown.

Literally.

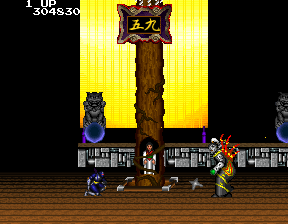

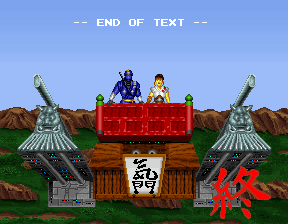

Unsurprisingly, the story is heavily pared down. It’s really only an ending cutscene, though it’s a pretty cool one by 1988 arcade standards. Shiranui rescues the princess – Saki is her name – , the cannon blows up the castle, and they barely escape on a flying sled (yes). Akagi and Taromaru don’t exist in this telling, but the main villains and enemy types appear, along with a few key locations.

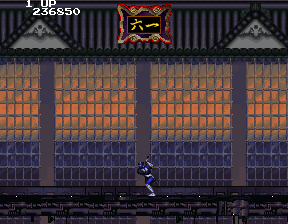

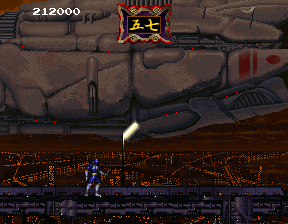

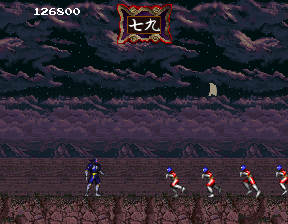

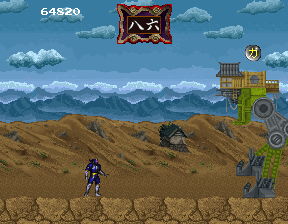

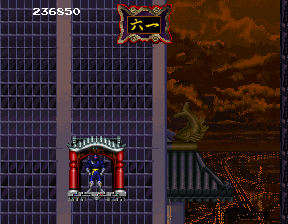

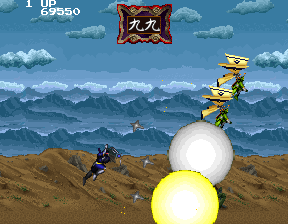

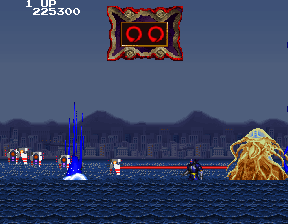

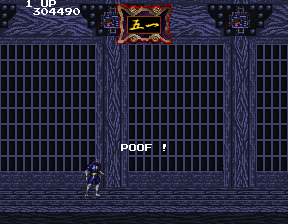

Most of the environments unique to the game are rather bland. There’s a modern city with skyscrapers and elevators, a sort of semi-futuristic base with a clockwork theme, and a series of bridges over shallow waters, all themes Shinobi and others had already handled with more personality. The basic gameplay is similar to Shinobi, too, in that your actions are limited to jumping and throwing projectiles, which turn into sword hits when you get close to the enemy. You don’t just die in one hit, though; you start out with a fair amount of health, which is displayed as kanji at the top of the screen rather than as a bar or a number, an idea first used in Namco’s earlier Genpei Toumaden.

Full health.

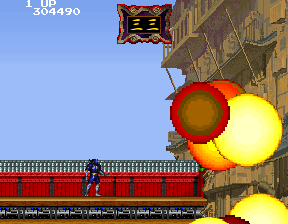

While by no means ugly, the visuals are somehow less appealing than either Splatterhouse and Bravoman, despite the more powerful hardware. This is because Mirai Ninja opts for a zoomed-out view, in which the sprites are tiny and the backgrounds a bit empty. The protagonist might look nice on the arcade flyer, but you can’t make out the details of his design at all when you play – a strange choice for a game whose producers went to the trouble of hiring a pro character designer from outside the games industry. One way in which it does take advantage of the System 2’s capacities is in its occasional use of rotation effects, notably during a boss fight in which the room rotates by 45 degrees every few seconds. There’s also some pretty nice parallax scrolling going on with the skies in outside levels, and some well-drawn detail here and there.

The levels feel somewhat empty in gameplay terms, too, as you regularly find yourself running through long stretches with no enemy or obstacle. There are multiple paths to get through most levels, but you can’t actually backtrack for more than a few steps, so you don’t get to explore these until you replay them. There really isn’t much to find besides a few health restoratives and short-term power-ups, anyway. Still, it’s a fast-moving game, and most levels can be traversed in under two minutes or so, so the first half remains kind of fun despite the lack of adversity.

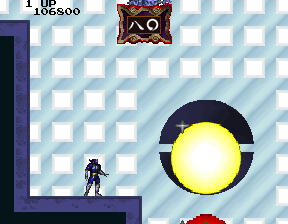

Three years before Super Castlevania IV.

Things change when you reach the 6th level. Suddenly, it becomes hard not to get overwhelmed by enemies that seem strangely hard to hit. Unlike most older action games, which tend to restrict the amount of projectiles the player can have on-screen to just a few at one time, Mirai Ninja requires that you mash the button like a madman in order to keep the steady flow of shuriken the tougher parts ask for. Normal enemies don’t respawn, so you might be tempted to advance slowly in order to handle them in small numbers, but you can’t be too slow, as small hovering devices equipped with lasers will start to show up around you and almost certainly kill you within seconds if you’re taking too long. Even if you manage to kill a few, they will continue to spawn faster than you can move, sometimes accompanied by other enemies, until you inevitably get overwhelmed, forcing you to restart the level as the game does not feature respawns or checkpoints. This is especially cruel as there’s no visible time limit to indicate that this is about to happen; you’ll just have to learn through repeated deaths which levels want you to keep it moving.

Basically an execution.

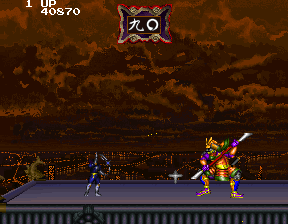

The boss patterns are simplistic, at least when they have patterns; a few have unavoidable attacks instead, and can only be beaten if you reach them with enough health left and manage to mash the attack button fast enough to get them before they get you. This is made harder by the fact that you only recover some health when you beat a level, and health restoratives, which are initially plentiful, become very rare later on. Sometimes, you have no choice but to kill yourself and waste a credit just so you start a level over with full health.

Bizarrely, two of the level settings are repeated a second time with new layouts. The second version of the clockwork stage actually requires precision jumping, which is extremely finicky as it’s easy to either undershoot or wildly overshoot and end up far past the cog you were aiming for.

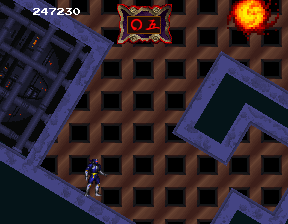

Worst of all, though, is the final level.

It isn’t uncommon for late ’80s side-scrollers to feature some kind of maze towards the end. This one involves multiple floors than can only be accessed by jumping down the right holes, and statues that act as dead ends and send you back to the beginning. Of course, you still can’t backtrack; run into a statue, and you know you’ve wasted a life, because being sent back causes those same laser bots to appear and quickly terminate you. The amount of trial-and-error necessary to chart out the proper path without a guide is enormous, and the idea that players would put themselves through this in an arcade setting, staying on their feet for hours while blowing untold amounts of quarters just to get through some asinine maze, is complete madness. Should you figure out the path, you’d better make sure you don’t forget it, because the final boss’ final form features unavoidable attacks, too, and even with full health, it amounts to a particularly difficult button-mashing trial.

This is it.

In the end, Mirai Ninja‘s obscurity is probably no mystery after all; it’s just not a very good game.

Keita Amemiya concentrated on film and television over the next few years. His next video game job would be the Hudson Soft-published Hagane in 1994, whose ninja Robocop concept is strikingly similar to Mirai Ninja‘s, though the games themselves aren’t.

While Mirai the game is nearly impossible to play today outside of emulation, the movie is still readily available on DVD in Japan, and can be found with acceptable English subtitles without much difficulty.

AAC Stunts: These guys played some of your favorite Metal Gear Solid characters.

As a last aside, the stuntmen who performed most of the fighting would go on to do the motion capture for games like the Virtua Fighter series, Metal Gear Solid 2 & 3 and Code Veronica some years down the line. Like Keita Amemiya, this was their first movie job.

LINKS / SOURCES:

Crowd Inc – Keita Amemiya’s company website. Lots of websites in English credit him for things he didn’t do – this is a much better source.

AAC Stunts – The stunts company that began with Mirai Ninja.

Japanese Wikipedia page on Keita Amemiya.