Mesopotamian mythology, originating from the earliest footnotes in human history, is a popular subject in pop culture when it comes to the mystery of ancient wonders. In Japan, one of the most instrumental works that solidified its image is The Tower of Druaga, Namco’s 1984 arcade game that attracted the public into Gilgamesh’s adventure through the Babylonian tower and its insanely brutal mazes. While its massive success would prompt the company to turn it into a long-running franchise, it also provided groundwork for their lesser known title: The Tower of Babel, a 1986 Famicom puzzle game that takes Druaga’s premise and runs in substantially different direction. This game is noteworthy for being one of the first Namco titles developed exclusively for home environment, instead of no-frill ports of their older arcade hits. It was designed by Hiromu Nagashima, previously responsible for the arcade/NES shoot-em-up Sky Kid.

The Tower of Babel (or just Babel, as the box cover and the title screen calls itself) involves an expedition into the eponymous labyrinth once again, this time putting you in control of the archeologist Indy Borgnine. He is in search of the fabled Hanging Garden of Babylon at the top of the tower. To get there, he must survive 64 levels worth of a trial and monsters that reside them, not to mention dealing with riddles left by the ancients. Your goal is to guide him to each floor’s exit, collect the crystal balls that unlocks it along the way, and try not getting him killed.

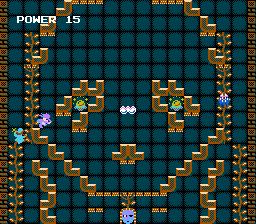

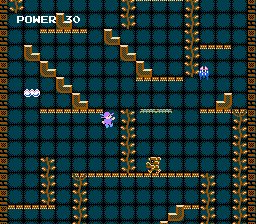

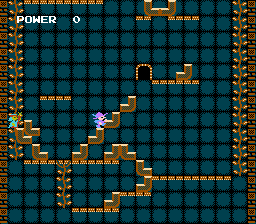

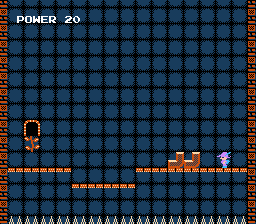

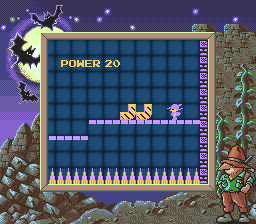

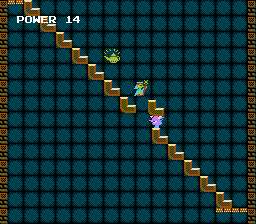

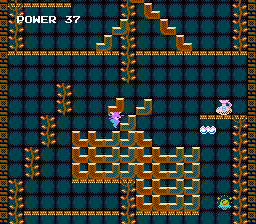

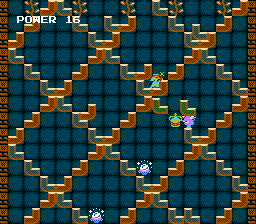

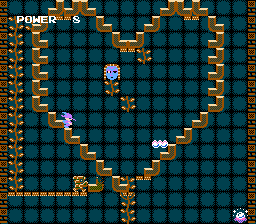

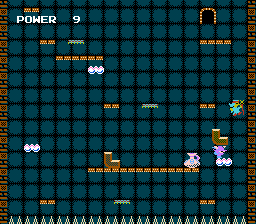

Although the gameplay takes place in a side-view perspective like Solomon’s Key and Milon’s Secret Castle, only with occasional addition of vertical scrolling, it’s not really a platformer. Unlike his namesake from Hollywood, Professor Borgnine isn’t much of a versatile adventurer; he can’t jump across the smallest gap or onto higher platforms, and will die instantly the moment he makes the slightest contact with enemies. Instead, you have to utilize his ability to raise and move the L-shaped blocks littered within the tower, which can be assembled to a stairway to upper part of the room.

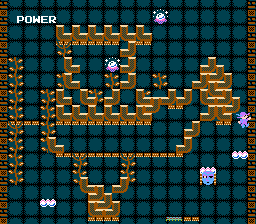

Every level hosts a string of blocks you can rearrange at your will, so that you can come up with your own architecture that’ll help you fetch crystal balls and make your way toward exit. Each lift depletes the power meter, however, and if you try to pick up a block without any, Borgnine will collapse to his own death. You also need to worry about the monsters, including the bats that lurk around rooms, and the golems that conjure blocks out of thin air (though some levels require you to take advantage of the latter). The most dangerous of all are the Ur-priests, who not only try taking the shortest path to catch you, but almost immediately respawn after you bash them with blocks.

With your main objective being the balance between obtaining keys and fending off your pursuers, one can draw some parallels with Broderbund’s all-time classic Lode Runner. (In fact, that game had already earned national reputation in Japan, with Hudson Soft releasing its NES port a couple of years earlier, so there’s a good chance it had a strong influence on Babel‘s conception.) Only here, the game puts more pressure on the player by limiting the total amount of action they can take. Its mechanical dexterity is both the strength and the weakness of Tower of Babel. It’s rewarding when you manage to put the pieces together and pull off the correct solution while outwitting your chasers, but achieving so can take so much tedium in the process, especially the later levels tend to weigh on a lot of block shuffling. And unlike Lode Runner, actively hunting down enemies is usually a bad idea, because it will leave less ammunition to complete the puzzle, possibly trapping yourself into unwinnable situation. Rather, it’s wiser to employ indirect measures to keep them away.

There’re some other oddities that are more debatable. Toying with blocks in certain manner (like juggling an Ur-priest with them) can make bonus items appear, which grant things like temporary invincibility, faster walking speed, and the ability to walk through blocks. More importantly, these goodies add to the score, which then rewards you with extra lives. The problem is that you start with merely two lives from the outset, and given how many stages are designed in a way you need to fumble around to get a good grip of them, death will come faster than you’ll know it. Thankfully, the game gives out passwords per level, so you can experiment as much as you please without real punishment. But this adds a few more extra steps to resume your progress, as each continue requires manually putting in the password.

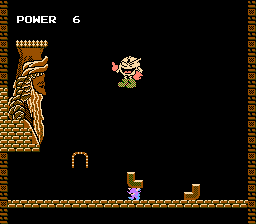

By far the most controversial part, and one element that has been carried over from Druaga, is the inclusion of intermission levels that show up every eighth floor. These rooms are comprised of incredibly easy puzzles, but you know there’s something more than meets the eyes, playing ominous music and decorated with antique sculptures not found in the entire rest of the tower. Although the game never tells you about this, what you should do here is to take a shot in the dark about arbitrary behavior – like hugging a wall for ten seconds while holding a block – that’ll reveal each level’s designated symbol (one of them is yet another Pac-Man cameo). However convoluted and daunting this may sound, ignoring these sections will make you pay for it. At the entrance of the Garden, the game suddenly asks you to type the “Big Password” deciphered from these stages, else it won’t let you see the ending. For a game that has consistently been about brain-teasing challenges, this is such a huge slap in the face. Nowadays, though, you can just look up the combination on the internet. Either way, passing this final test will teach you a hidden command to access another, ultra-hard set of 64 levels.

Tower of Babel was one of selective Famicom titles that saw simultaneous arcade release for the Nintendo’s Vs. System. (This version is undumped as of yet, so it’s hard to tell how much it differs from the console release.) Ultimately, it didn’t seem to make as much impact as Namco’s other Famicom games like Battle City, but it did end up on a few complications the company likes to put out every so often. Since the original game didn’t require a technological powerhouse to begin with, all of these ports are faithful conversion on their own. The exception is the PlayStation port, which comes with a remake that applies some major tweaks to the game design.

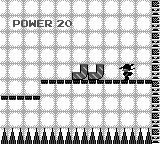

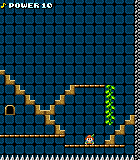

The first of the bunch is the Game Boy version included in 1997’s Namco Gallery Vol. 3. This port does not downsize the levels to accommodate its smaller screen estate, meaning you have to pause the game to see the whole area. This makes much more annoying to plan out your move, especially whenever the Ur-priests are present. It’s the same game through and through otherwise, but there’s no merit to play this version unless you must dust off your Game Boy, or want to see the added border when played with Super Game Boy peripheral.

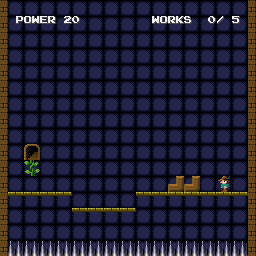

Next is the PlayStation version from 1998’s Namco Anthology Vol. 1, which contains both the emulation of the original game and the aforementioned remake that introduces quality-of-life improvements, on top of the benefits of revamped graphics and music that provide much needed audiovisual variety. The passwords are replaced with standard save system via memory card (which also supports custom level editor), and the lives have been eliminated completely, saving you from sitting through the game over screen every other minute. Instead of the latticed background that worked as an index, you can manually toggle the grid on the fly with the triangle button. It irons out many of the bugs in the Famicom version, too. There was one particularly aggravating glitch that makes you float a bit when you walk in or out of moving platforms, leading to all kinds of pain if you tried to convey a block through them. The remake fixes the quirks in the game’s engine so that it isn’t nearly as troublesome.

The level structure went through complete overhaul as well. The game now opens a gauntlet of eight levels at once each time, giving you leeway to tackle them in any order. The intermission levels are still present, but you can acquire in-game instruction to trigger the symbol by gathering the manuscript pieces found in regular levels. These collectibles are optional, so you can still solve it in the old way, should you choose so. Most of the levels are swapped around or entirely new (bumping its number up to 192), and the difficulty curve is more friendly in general.

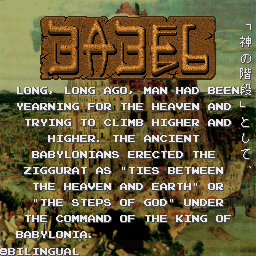

An unofficial Sharp X68000 version was released around this time as well, converted by anonymous programmer known as γ-AWC. It’s based on the Famicom game, so it lacks the niceties from the PlayStation remake, but the redrawn graphics are still a marginal improvement. There’s also a new arcade-style opening crawl at the beginning written in both Japanese and English. If you happen to dislike the changes made in the remake, this is a pretty good option.

There were at least two mobile ports for Japanese cellphones in the 2000s, again featuring updated graphics. Finally, the original Famicom game was re-released on Wii U Virtual Console in 2015, and made available in Namcot Collection (2020) for Nintendo Switch. The Virtual Console version edited the title screen to spell “The Tower of Babel” for some reason.

While Tower of Babel remains mostly neglected in Namco’s retro throwback policy (outside of its main theme making it in Taiko no Tatsujin and The Idomaster series), it received a webcomic adaptation in 2014 as part of Namco’s ShiftyLook project. Serialized by Sam Logan and Shannon Campbell, it told the story of Minnesota Borgnine, the hero’s granddaughter who’s forcefully tasked to investigate the tower’s resurrection in the modern world. It ran about two months before the ShiftyLook division was abruptly taken down, leaving the plotline hanging without any sort of closure.

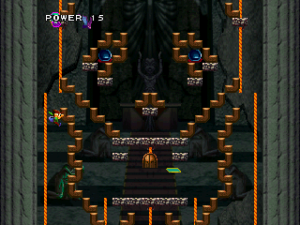

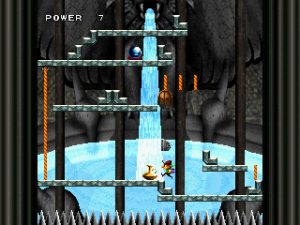

Screenshot Comparisons