There are three early Western PC Role Playing franchises that just about every fan of the genre knows. Ultima, Wizardry, and Might and Magic. Wizardry is currently active in terms of single-player PC RPGs, though basically only in Japan. Ultima‘s last single player installment was Ultima IX in 1999. The Might and Magic franchise, originally published by New World Computing and 3DO, remains active through spinoff games, like Heroes of Might and Magic and Dark Messiah of Might and Magic on the PC, along with Clash of Heroes on the DS, all published by Ubisoft, the current owner of the property.

Might and Magic Book One was published in 1986 by John Van Caneghem and his company New World Computing. Like many other early computer RPGs like Akalabeth or Angband, Caneghem initially handled distribution of the game himself from his apartment, until he could arrange a publication deal with a larger company for broader distribution (originally Activision). The game was designed to be a first-person Dungeons & Dragons-style RPG, as was popular at the time, but with a slight twist. Where the Ultima series kept the player in the 3rd person most of the time, except for dungeons, and Wizardry never really left the dungeon, Might and Magic would keep the player in the first person the whole time – in towns, in dungeons, and when exploring the world – a concept that’s certainly familiar to people who’ve played modern Western RPGs like Fallout 3 and Oblivion. All of this was meant to immerse the player further into the game’s world.

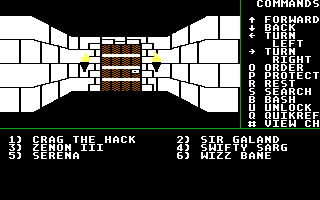

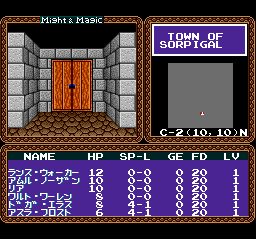

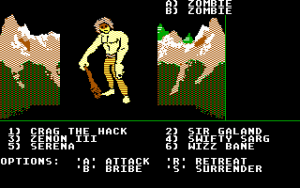

The player begins the game in the home computer versions by generating a party of up to six characters, with seven stats ranging from three to eighteen, with most of the stats, character classes and alignments being analogous to stats in Dungeons & Dragons (although it makes a point of always changing the terminology).

Following the simplified CRPG interpretation of the D&D rules popularized by Wizardry, the game does make two notable differences to streamline the gameplay – there are only three alignments (Good, Evil and Neutral), and spells don’t have to be memorized, with casters instead using a pool of magic points for handling spell-casting. Additionally, classes that would have alignment restrictions in Dungeons & Dragons or Wizardry, like the Paladin, have no such restrictions – even Paladins can be evil or neutral.

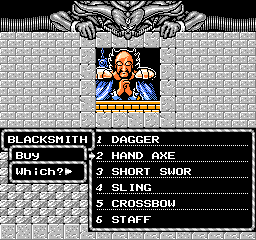

All the basic rules are extremely straightforward, accessible, and easy to learn. Only after this is where things get obtuse and a little more difficult for newcomers. The first problem is starting out – everyone begins with a club and no money, forcing you to go out and fight enemies for money for better weapons and armor, plus more food and torches so you can travel into the game’s dungeons. Because of this, Might and Magic requires the player to grind even more in the beginning than in other RPGs from the same period, which provided the characters at least a small amount of money from the start.

The next problem is the encounter rate, which can be glacial. The player can wander around the dungeon and outside world for quite some time without encountering any random encounters. While they do happen, they’re just rare enough that they make grinding for money and levels take much longer than necessary.

Thirdly, unlike the Dungeon & Dragons game and contemporary computer RPGs, you receive no information in the game or in the documentation about to how many experience points you need to go up a level, unless you go to the training hall to ask. Going up levels also costs money, forcing you to manage the costs of getting the equipment you need to continue and the costs of training to level up your party. While not unheard of – the first edition of Dungeons & Dragons did require the character to spend money in order to level, too – the low encounter rate makes things more difficult.

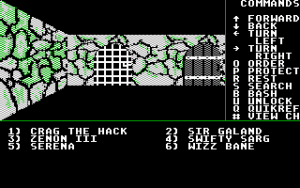

Further, the game has little story direction at first. Even the manual contains no story information at all. While you do receive quests that progress the main plot and other side quests from NPCs as you go along, at the start you have nothing. Also, while there are spells that will give some information on your current location, there is no auto-map or other sort of “map view” in the game, meaning that the player will need to break out ye olde graph paper to maintain orientation not only in cities and dungeons, but the areas between towns as well.

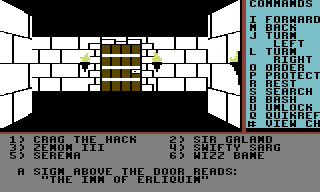

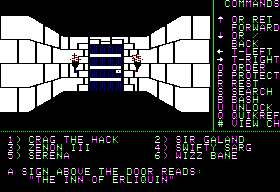

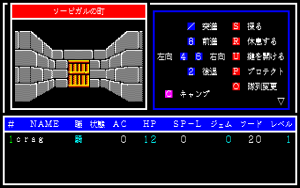

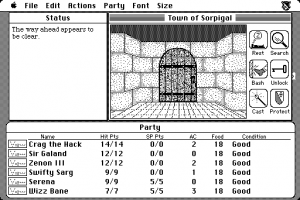

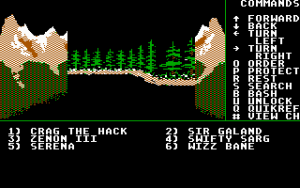

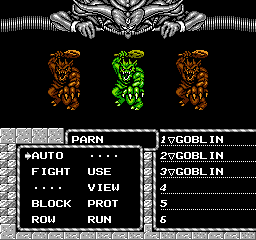

Being a mid-80s home computer product, the game is light on graphics and sound. There is very little music; only a musical ditty on the title screen and a small fanfare when enemies are defeated. When navigating the environment you can recognize the labyrinthine walls of the area you’re in by their flat textures, whether it’s a town, dungeon, or forest. NPCs and monsters have their portrait displayed when you encounter them. After combat has begun, however, the game switches to a text only screen where the fight is managed.

In general, while the home computer version of the game does innovate in some areas that other games in the genre hadn’t succeeded at, it doesn’t stand up well in comparison to the remakes that would come later. The only strong argument in favor of playing the home computer version of the game is that your save, and thus your characters, can be carried over to the next game in the series.

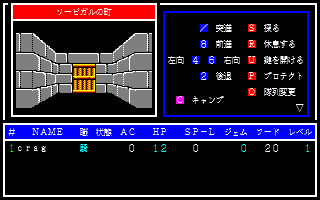

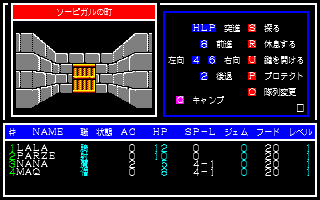

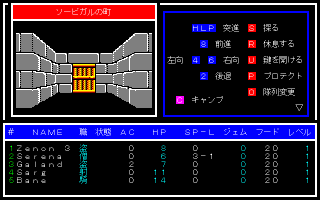

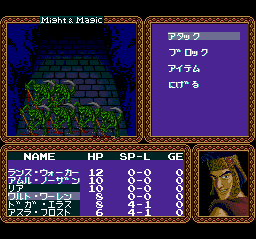

Might and Magic was brought to almost every contemporary Japanese computer system by Starcraft, who also published Ultima and several other WRPGs in the Far East. The few well known versions feature a common set of new graphics, but of course are all in Japanese, without a nifty multilingual feature like the Japanese Wizardry ports. The title screen in these versions is based on artwork by Frank Frazetta; It’s doubtful whether this happened with permission. The PC98 version runs at a higher resolution, which allows for crisper interface text, but otherwise they’re mostly very similar.

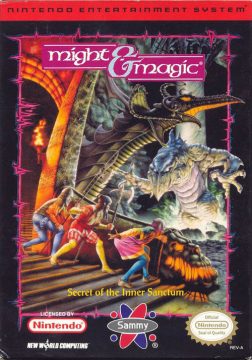

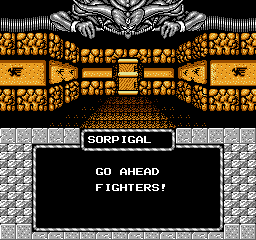

The NES version, which was ported in 1991 by G-Amusements (a division of the Japanese publishing company Gakken Co.) takes full advantage of the technological changes the five years since the game’s original release had brought on. The overall color palette of the game has more variety, with city walls depicted in bright earthen tones, a blue sky when exploring the outside world, and so on. The title theme is Pachelbel’s famous Canon in D. The game even has musical themes for menus, exploration of dungeons and towns, and for the combat. The encounter rate has also been increased, allowing players to earn gold and experience more quickly.

This version also includes an auto-map, which is visible when the player presses Select in an area with an active light source. While the maps don’t include any notes on shops, traps, or fixed encounters in the area, it is automatically updated when walking around whith an active light source equipped. Dungeons are fully navigable without active light sources; Just the automap feature requires them.

There are some minor problems with this – light sources, like torches and light spells, only last for one square – once the player moves to the next square, light spells must be re-cast (using up more magic points), and torches much be re-lit. However, torches have multiple uses, making them considerably more valuable than light spells. Also, the overworld automap doesn’t work the same way as the town and dungeon maps; it only shows the party’s position on the world map, with no landmarks (like castles, dungeons or towns) given.

Other than on home computers, there is no opportunity to roll one’s own party at the beginning. Instead changes can be made by finding a guild hall in the first town, which will let you reroll characters. However, all gained levels, money, food and equipment on the character is lost in the process, and it’s difficult, if not impossible, to shuffle gold from one character to another.

That said, the NES version of the game is a vast improvement, with superior graphics, sound, and gameplay, and is preferable over all the home computer versions.

The PC Engine CD-ROM version, released only in Japan and developed by NEC is very similar to the NES version, but with some subtle differences. The automap is displayed on the main screen, rather than a separate menu. Since the game was released on a CD-ROM system, the developers were also able to include CD quality music, along with a fully animated and voiced opening cutscene, explaining some of the world’s back-story, and depicting the characters arriving someplace by boat, only for the ship they arrived on to be destroyed by a magic attack from a Centaur immediately after, and the party to be teleported to the starting city of Sorpigal.

This version of the game was only released in Japan, so the game’s menus and dialog are all in Japanese. As no fan translation has been released yet, it can only be recommended to players who understand Japanese or have the game essentially memorized.