Over the last decade, gaming in general has undergone a transformation. Simplifying gameplay while diversifying its audience. Mainstream gaming has homogenized, newer more social and “casual” genres have emerged, other more hardcore ones have disappeared or transformed into something more acceptable. One of these “casualties” is the first person variety of dungeon crawler.

Back in the ’90s, PC owners were lucky to see many of them, including the likes of Ultima Underworld, Lands Of Lore, Might & Magic, Wizardry and The Bard’s Tale. Console gamers were also treated to many episodes of Wizardry, Shin Megami Tensei, and the likes of Shining In The Darkness / Holy Ark. All of these games emphasised first-person viewpoints, controlling a single character or a party of characters. Combat was in some cases turn-based e.g. Wizardry, in others real-time e.g. Ultima Underworld. Character creation, leveling, statistics were all crucial to progress, otherwise an inattentive player may reach later game levels severely underpowered, and often sheer grind wasn’t enough.

Returning to the present day, the first-person dungeon-crawling RPG is currently limited to the Elder Scrolls series and a scant few Nintendo DS games. Otherwise, first-person is out. Third-person is in. Character generation is (mostly) out, hack-and-slash is in. Convoluted maze-like level design is rarely seen, and more linear, easily-digestible levels are the norm.

This is likely why King’s Field is not only a lesser-known series in the west, but has even been completely forgotten by its developers. It embodies many of these “retro”, hardcore gaming traits, and a lot of people are likely to try it and run for miles in the total opposite direction. On the other hand, perhaps you prefer a more old-school approach? If the idea of being lost in mazes with only your weapons, magic and armor to defend you seems appealing, then King’s Field will be of great interest.

King’s Field was produced by the Japanese software developer From Software, otherwise known for the Armored Core series, the cult classic PlayStation 3 release Demon’s Souls, and its Xbox 360/PS3 spiritual successor series Dark Souls. It is played in the first person, with full 3D movement, although it does not at all resemble a first person shooter, particularly in how slowly your character moves.

Playing the game, little concession is made to the player. You begin each game with weak attacks, little or no magic, healing items or much of note. Expect regular one or two-shot kills from even the first enemy encounters. Visuals are spartan, oppressive, not helped by the PlayStation’s rather limited 3D capabilities. Levels comprise mostly of corridors, rooms, and corridors (with some occasional and major exceptions). Locked doors requiring the usual round of keys – not all are reusable – and they become a focus for exploration.

There is little, if any, direction given to the player in any of the games. The experience of playing King’s Field is ultimately slightly confusing at first, but ultimately massively open-ended and atmospheric. The purpose of the gameplay is simply a little more involved than hacking and slashing, and the games don’t play all of their cards immediately. Discovery is absolutely crucial, and a main draw in King’s Field.

There are four primary games in the series – the first, second and third on the PlayStation, and the fourth on the PlayStation 2. Westerners were lucky enough to receive English translations for most of the mainline games, as well as the off-shoots Eternal Ring and Shadow Tower. What possessed From Software to make this effort isn’t clear outside of whatever success was received by the first game in Japan. The games are not text-heavy though, which is traditionally a major issue during translation of a game. For reasons unknown, the first King’s Field never made it to the west and as a result localized editions of the second two games were “re-numbered” accordingly. King’s Field 2 was the first game to receive an English translation, and was released in the USA and Europe just as King’s Field, without a number. Kings Field 3 was again “re-numbered” for the West, and made it to the USA as King’s Field 2. There were also two PSP games titled King’s Field Additional, as well as three mobile games, but none of these have made it outside Japan.

First-person combat on consoles is a notoriously inaccurate affair. The first three King’s Field games all appeared on the original PlayStation, and without analogue controller support. This inevitably leads to over-pressing of the directional-pad, a lot of L1/R1 strafing and swinging wildly at the appendages of one’s nearest adversary. What seems like a crapshoot at first eventually becomes second nature, and even compelling. King’s Field balances a sense of risk vs. reward near-perfectly. Often the player will be risking a one-shot kill while circling a particularly difficult enemy, however once said enemy has been downed they will boost your strength and/or level, and may also open a path to a much-needed healing item.

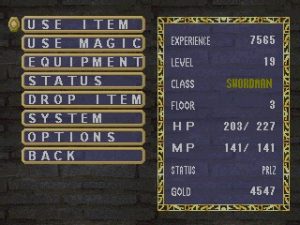

The RPG “system” in the game initially seems basic. You have no party, and are entirely alone. The HUD in all four games have gauges denoting your HP (health-points) and MP (magic-points), as well as a compass, displayed at all times. These are augmented with HP and MP “strength meters”. As you stab, smash or hit with your weapon, the strength meter empties entirely and must refill before you can throw another hit. Melee attacks can be made at any time, but casting magic requires a FULL MP strength meter, even if you wish to call upon a defensive / passive magic in the menu. Melee attacks with maximum possible damage require a full HP strength meter. If you attack while the meter is in a less than full state, your attack power will accordingly be weaker.

There are many other stats in the game, including broad “strength” levels for your magic and melee attack strength. Simply, this means that it is possible to “level up” your attack power, and magic power. As hinted above, this happens while incurring damage upon enemies, with melee or magic attacks. You will also level up in the traditional way when attacking enemies, but this is less important to progress.

There are many player equipment slots: one for a weapon – there’s no dual-wielding – many for various armor pieces, a magic slot to denote which offensive magic to attack with, and an item slot that you’ll likely reserve for healing. As well as the “offensive” magic there are defensive / healing magic that cover the usual heals, antidotes and resistances as well as some unique extras. These defensive magic are cast within the menu. It works well enough, but it will feel a touch clunky to those used to modern RPGs where players may assign whatever magic they wish to hotkeys.

Unlike most RPGs, you don’t have stats for intelligence, dexterity, and so forth. The stats here are limited to earth / air / fire / water attack and defense, plus your attack and defense against different types of attack e.g. slash, stab and swipe. The game is heavily combat focused, rather than “character-focused”, and the expert King’s Field player will choose different weapons for different occasions; skeletons tend to go down faster with a spiked mace.

The menus are simple, effective, and employ large fonts that are clear and readable. Even in the packed statistics pages, it’s easy to understand everything. Save points can be loaded at any point, any time, but only saved at specific “crosses” or altars dotted around the levels or maps, and sometimes these are located very far from one another! The options menu gives some control over enabling and disabling sound effects, music, and even the head-bobbing. Useful if this makes you queasy!

Shops are a regular feature in the game but – unlike most JRPGs – shops locations are not limited to towns, and they are usually dotted around the gameworld. Often NPCs can be found in fairly random locations, buying and selling items, or offering other services. The latter particularly becomes a major factor of progress in the second game. Gold is the currency of King’s Field, always limited and important in the first few hours of play, it becomes somewhat useless once you reach the latter stages and have all the healing items, armor and weapons you need. Since many pieces of armor and weapons can be found in treasure chests littering the game world, you’ll likely limit your purchases to other items, if you want to make progress.

As should be evident, King’s Field is a rather different beast than normal JRPGs. The plots are simple but effective, the cutscenes are few, and NPC banter is limited though often interesting. Most of the player’s time in a King’s Field game will be exploring dungeons, finding items, using keys to unlock things and strafing around enemies. This is also where the critical divide surrounding the game stems from: King’s Field is a slow game. Progress, combat and everything in the game is taken at a far more deliberate pace than a lot of other games, particularly console games! Many players hate this on principle, or worship the games for it.

It’s also worth complaining about the player character’s slow turning speed in King’s Field. To call it slow would be accurate, particularly in the first and most especially the fourth game. You will either adjust or throw down your controller in defeated agony. It could be argued that it adds much tension in combat – and often it feels that way – however just as often you’ll find yourself punched and scraped by enemies off the side of your vision, and the many seconds it takes to turn around to see them feel agonisingly long. Forward and backward movement isn’t all that slow, though (with one major exception we will come to), but it’s only in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th game that your player character can run, and this will completely deplete your attack and magic strength gauges.

The visuals are typically not great, as in general the textures and models in first three games are spartan, repetitive, and low-poly but effective. As the fourth King’s Field was on PlayStation 2, however, the visual update was dramatic.

There’s a lot of very well composed and memorable music in the King’s Field series, however because specific themes are used for specific levels (King’s Field 1) and sections (King’s Field 2 and 3), you’ll be listening to the same melodies on repeat for quite a while. As for sound effects, those in the first game are effective but come across as rather muffled and a touch jarring. The sound effects in King’s Field 2 and 3 retain the muffle but feature thunderous door rumbles, quite unsettling enemy sounds, clashing weapon effects, and – particularly – tormented screaming when you die. The fourth game improves on this a lot but all four games drip with a tense, uneasy atmosphere, as a result of their sound effects.

Unfortunately, despite aforementioned PSP and mobile King’s Field releases, From Software have effectively forgotten all about the series. This is a crying shame, and Demon’s Souls third person hack-n-slashery isn’t quite a suitable replacement. Despite this, Demon’s Souls’ popularity gained From Software a lot of attention in the West, so let’s hope that this may bode well for potential additions to King’s Field in future.

In short, King’s Field is that rare breed: an immersive simulation. A player is placed within a world that has its own rules, and said player is allowed to interact and discover, using a first-person viewpoint, with that world and its inhabitants. King’s Field doesn’t quite have the depth of Ultima Underworld‘s character creation, or the interactivity of your average Thief or System Shock 2 mission. But it is, nevertheless, an immersive simulation combining simple but effective melee combat, magic, dungeon crawling, compelling difficulty, exploration and personal discovery. It stimulates both sides of the mind, and is simply a very good series of games. If you like a challenge!

A huge thank you goes to Magnus Guyra for some vital corrections to the article, and miscellaneous useful information. Cheers Magnus!

The first game in the series bears the catalogue number SLPS 00017, and was released in Japan on December the 16th, in 1994. This was only 13 days after the PSX went on sale in Japan. How many consoles could boast a dungeon crawler – of all things – as launch title?

According to forums, the game was a massive success in its native country. The five sprawling, dark, oppressive levels, combined with an eclectic and odd-ball collection of enemies and the distinctly tense atmosphere, still make for a compelling experience. At this point, dungeon crawlers on consoles were few and far between. Sadly they still are, but it’s easy to see why a fanbase would build out of such a game.

The plot involves a fair bit of backstory, but the gist is that you are royal-descendant John Alfred Forester on a quest to find your father and rid the land of Verdite of an evil plaguing an abandoned cemetery. King’s Field doesn’t throw a ton of lore or exposition at you, there are very few NPCs in this game and most of them aren’t particularly talkative. It’s no wonder really, as the cemetery is a pretty wretched place to be stuck in… (and this is meant in a positive way: the level design is already appropriately claustrophobic.)

As previously mentioned, you start out utterly useless. Only a few doors away from your starting position is a skeleton that can down you in two blows. There’s absolutely no hand-holding, and you will have to get used to circle-strafing the enemies as soon as possible if you want to progress. The broad structure of the game can be boiled down to explore, find a key, open up previously inaccessible areas, find another key, use that to open previously locked chests and doors, find another key and eventually find a teleport to another level. Progress in the game centres entirely on this mechanic.

The usual array of swords, shields and armor parts can either be bought from shops or found in chests or secrets as you trudge around the corridors. Unlike later King’s Field games, magic is learned only by leveling or talking to certain NPCs. There are no crystals, and you start out without a map. You can go where you want – keys allowing – and do as you like. The sense of freedom King’s Field offers must have made many Japanese gamers feel satisfied at the time, and it still feels compelling today.

Since this is one of the very earliest PlayStation games, the visuals are as you would expect. Very low-resolution textures, low-polygon NPCs and enemies, and absolutely no sort of filtering effects. This is bare mid-’90s 3D as became the norm for PlayStation games, in all its texture-warping, poly-edge-breaking glory. Often there aren’t even any specific door textures: apart from the church entrances, the only way to tell that a door is a door, is that they are all indented slightly from the walls. In defense of the game, it still looks tremendously atmospheric. The low draw distance is hilarious at first, but when you sit down and play the game, it becomes absolutely crucial to the atmosphere. The oppressive repetition of the corridors, textures and rooms looks initially embarrassing, but ultimately tremendously effective in making the player feel alone, weak and nervous.

Secret doors are merely stumbled through in King’s Field but this would change in future. There are otherwise two notable features of the first game that do not feature in the others. First are the regular and various bottomless, spiked and poisoned pits dotted around the floors. Pits would appear on occasion in King’s Field 2, but they would always lead somewhere. Here, a bottomless pit kills you immediately. There is a way to overcome them later on in the game, but it isn’t surprising that From Software didn’t bother with these “pits” in future games.

Second, the level design broadly comprises of five stages, and while they vary in style and are interconnected by teleports as previously stated, they are rather “static” in comparison to the sprawl of the following games. The physical structure of a level feels not dissimilar to Ultima Underworld, where there is a set physical width and breadth possible to explore in each floor. The game engine is capable of sloped ground and walls – and there is much of both – but unlike the persistent open world of the other three games, here each level is loaded separately rather than streamed on the fly. This distinct separation of the levels lends the game a more arcade feel.

Ultimately, the game feels a bit shonky, slow and hasn’t aged terribly well. But it still has tremendous doses of atmosphere and is a very playable dungeon crawler, though there were better things to come. There was no official English release of King’s Field but a fan-made translation was released in 2006, and it became possible to play the game in full English.

Links:

Archive From Software Official game listing (Japanese)

Official From Software game listing (Japanese, PlayStation Books issue)

KnighTeen87’s fan-site (English)

Translated version download