Primordia is the product of a collaboration of sorts between Wadjet Eye Games and Wormwood Studios. It was designed and about halfway to completion when Dave Gilbert of Wadjet Eye approached Victor Pflug, the artist and team lead, about publishing the game. Victor agreed, and Wadjet Eye took over responsibility for the audio component of the game, as well as its marketing and distribution. They brought in Nathaniel Chambers to do the music, sound effects and voice processing, and enlisted their usual stable of voice actors.

Being responsible for some of the most popular indie graphic adventure games (Resonance, Gemini Rue, The Shivah and the Blackwell series), Wadjet Eye know a thing or two about the genre. As a result, they also offered quality control and coding assistance, which apparently included some advice about puzzles. But the art, writing and design, and the vast majority of the programming were all handed by Wormwood Studios, a team of four core members.

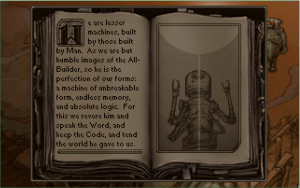

Characters Descriptions by Primordia writer Mark Yohalem:

Horatio Nullbuilt, v.5

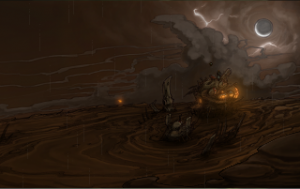

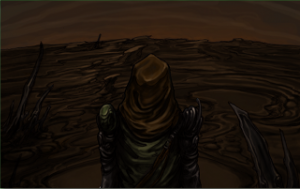

Horatio Nullbuilt lives in the vast wasteland known as the Dunes, a virtual hermit who wants only to be left alone to repair his crippled airship, the UNNIIC. Horatio is a master scavenger and can fix almost any machine, given the time. These skills, along with the UNNIIC’s powerful power source, have given him great independence, something he values immensely.

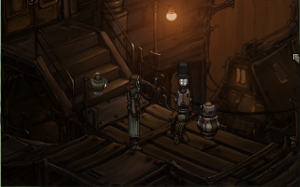

Crispin Horatiobuilt, v.1

Crispin is Horatio’s creation and sole companion in the Dunes. Unlike his taciturn creator, Crispin is equipped with a sarcasm co-processor that generates an endless series of snide remarks and annoying asides. Despite his grousing and joking, however, Crispin is fiercely loyal to his builder.

SCRAPER

The Subway Construction, Repair, And Precision Excavation Robot, known as SCRAPER for short, is an implacable, barely sapient machine built to carve through solid granite and withstand the force of tunnel cave-ins. Within its jet-black armored shell, simple programming directs SCRAPER to follow tasks to the literal conclusion, no matter the obstacles in its path.

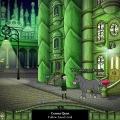

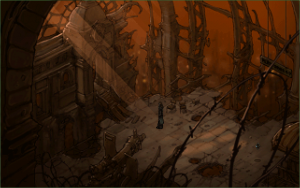

In a world that’s strangely devoid of humans and sunlight, you play as Horatio Nullbuilt. He’s a stoic robot who hangs out in the sticks with Crispin, a sarcastic friend of his own creation. Living on a sort of broken airship called the UNNIIC, they spend their days fixing things using scrap from nearby junkyards.

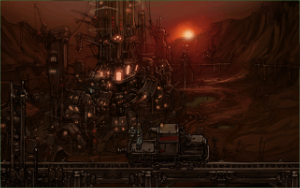

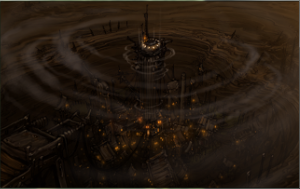

Immediately you get the impression that Horatio, if not happy, is fulfilled. Crispin, on the other hand, has itchy feet. Inspired by the constant propaganda broadcasts concerning the nearby city of Metropol, he longs to travel. Horatio, though, knows that to travel to Metropol will bring trouble. But one day, a formidable robot called SCRAPER (Subway Construction, Repair, And Precision Excavation Robot) shatters their world, stealing their power core and fleeing to Metropol. Yet whilst many games would use this as an impetus for immediate action (and possibly revenge), Horatio just… sort of gets on with things.

Your most pressing task is to repair your electric generator, without which Horatio and Crispin won’t survive for long. But as you can only find a temporary solution, it soon becomes necessary to find (or build) a whole new power core. Almost entirely driven by necessity, it’s only when all other avenues have been exhausted that Horatio reluctantly travels to Metropol.

It’s interesting to play as a character so unmoved by the world around him, especially since Horatio’s world is so undeniably fascinating. Beautifully drawn and rich in mythology, philosophy, religion and political intrigue, at no point are you told what to think, what to look at or even, really, where to go. Through subtle clues, clever wordplay and references that only initially seem obscure, this brilliantly realized world slowly reveals itself.

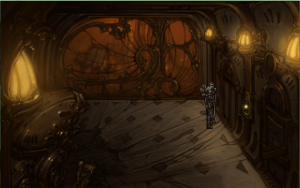

Of course, by the time you get to Metropol the stakes are raised significantly, until even Horatio admits that it’s no longer just about a power core. But to reveal even rudimentary details about the plot developments would be to rob newcomers of the considerable joys of exploring and learning about the world of Primordia.

Primordia is the sort of game that’s much happier in asking questions than it is answering them, but there are enough clues in the game for you to draw your own conclusions. Almost as soon as you reach Metropol you’re given the opportunity to research a variety of subjects at an information post. It’s easy to spend a long time there. It’s also rare that such a text heavy segment should be so engrossing.

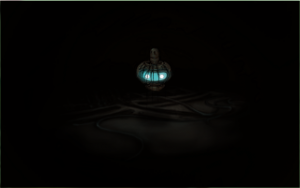

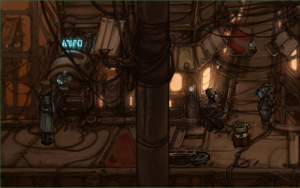

One of the major appeals of Primordia is the quality of the hand-drawn graphics. It’s simply stunning how a palate consisting mostly of browns and greys can be so lush. There’s around 50 screens to explore, and the level of detail in each is immense. Also worth noting is how human our robotic protagonists feel, all thanks to the friendly blue glows of their eyes.

The animation, though, is minimal. Most of the robots you encounter in the game either hover or remain still. Including Horatio, there must be as little as five robots in the game who move about using their feet. It’s here that the limitations of Primordia‘s visuals becomes apparent. The animation is slightly slower than the speed at which the characters walk, resulting in the occasional jarring stutter. This does little to make the game anything less than visually stunning, but it’s still occasionally irritating.

With its bleak yet beautiful graphics, post-apocalyptic setting and wise-cracking sidekick, one of the most obvious inspirations for Primordia is Beneath a Steel Sky. Yet the floating and vivacious Crispin also acts as the Mort to Horatio’s Nameless One, to the point that Primordia also comes across as a tribute to Planescape Torment. Along the way, you’ll also encounter references to Fallout and the Final Fantasy series. Even the amount of time spent in the first area is a nod to Baldur’s Gate II, which opens with a lengthy dungeon crawl before letting you explore the world.

Primordia is not a particularly long game, and the plot, when presented in a purely sequential manner, seems somewhat linear. But its quality lies in the depth of the world, and the questions it raises about progress, evolution, destiny and philology.

As for the interface, the left mouse button is for interacting, the right mouse button for observing. Puzzles often revolve around making creative use of information learned elsewhere, but Horatio is good enough to take careful note of any salient codes or gobbets in his datapouch. This datapouch can be opened anywhere at any time, even in the middle of conversations, saving you the hassle of having to take notes of your own. It also doubles as a map for ease of navigation, and you can later use it to access the memories of other robots.

The puzzles are a real mixed bag of nuts. Some of them rely on the time-honored system of combining items in your inventory and using them on other objects, but it’s rare that you’ll find yourself desperately using every item on every other item. Unfortunately, Horatio is a little too logical, as he will only do as you ask him if he’s convinced that he’s following the logical path. Fair enough, but it does grate a little during repeat plays, when you know what course of action to take, but Horatio just won’t do it. For example, one part of the game requires you to clean a pair of gears using oil, but Horatio will outright refuse to use an oil tap before he’s confirmed that the tap does indeed dispense oil.

But even should you find yourself stuck, you can always ask Crispin for help. He might mock you for your short-sightedness or your desperation, but beyond this there’s no real penalty for turning to him for advice. It’s a nice touch that not only makes you feel as though the game’s on your side, but also adds depth to the relationship between Horatio and Crispin.

There are only one or two really taxing puzzles. One involves settling a complex legal argument through solving a series of logic problems. The other involves cracking a 16 digit code of which you have all the components but not the order. But even these can be overcome just by asking around, or even by asking another robot to do it for you.

There are also multiple endings, which is determined you based on decisions made in the final few minutes of gameplay. It’s therefore possible to see all endings (of which there’s at least seven) just by saving your game before entering the final room and replaying events again and again. It’s hard to say which ending counts as the “best” ending, though some are undoubtedly less depressing than others.

Other than that, there are only petty criticisms to be made. Though the soundtrack is gorgeous in a bleak sort of way, and though most the voice acting is excellent, Horatio’s voice is quite grating. It’s the sort of flat grunt that you might expect from a brutish FPS protagonist. But that’s nit-picking. Primordia creates such an engrossing world that’s worth inhabiting. It’s a moving, thought-provoking and richly rewarding experience.