Ron Gilbert is one of the legends of adventure game design, having been one of the major driving forces behind Maniac Mansion and the first two Monkey Island games. Yet he left LucasArts in 1992, and while he’s stayed in the game industry every since, working on games like Putt-Putt, Total Annihilation, Deathspank, and The Cave, these really haven’t been adventure games, at least in the traditional sense. In late 2014, he pitched Thimbleweed Park on Kickstarter, rejoining to fellow Maniac Mansion designers Gary Winnick and David Fox, to a new point-and-click that recalled LucasArts’ glory days. After its success, it released just over two years later, in early 2017.

The story focuses on the eponymous town of Thimbleweed Park, a small town of about 80 people comfortably out in the middle of nowhere. At first, the game puts you in the role of a German visitor, given some rather suspicious instructions to meet down by a river under the cover of darkness. Predictably, things don’t go well for him, and he ends up as a corpse floating in the water. Two FBI agents – Agent Ray and Agent Reyes – show up to investigate the murder, and while they’re initially annoyed at the assignment, they each have their own reasons to visit this weird little place.

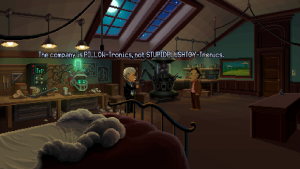

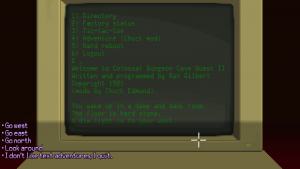

The game positions itself as a satire of the kind of oddball quasi-supernatural detective shows popular in the 90s, particularly Twin Peaks. Ray and Reyes initially seem like Scully and Mulder from The X-Files, though that particular resemblance is only skindeep. Otherwise, the town itself and its bizarre inhabitants take the forefront of the adventure. The denizens aren’t actually that concerned about the murder of the mysterious outsider, as instead they’re busy grieving over the recent death of Chuck Edmond, the local pillow magnate. Something of a local hero, his technical expertise created a town filled with advanced machines all quaintly powered by vacuum tubes (in addition to creating some damn fluffy pillows). But due to some mysterious circumstances, the pillow factory burned down, the local economy has since been ruined, and Chuck himself passed away. Of course, these incidents are connected, it’s just a matter of piecing everything together.

Beyond Ray and Reyes, there are three other playable characters. Ransome the Insult Clown is…well, his name is pretty self explanatory. He used to have an extremely popular act where he got in front of crowds and insulted them relentlessly, until he mocked the wrong woman and got himself cursed with the inability to take off his makeup. Combined with the disappearance of Chuck and death spiral of the town, he’s since taken to living alone in the derelict remnants of the circus.

More tightly connected with the plot are Franklin, Chuck’s nebbish brother, and Dolores, his daughter. You don’t get to play as Franklin for too long before he also meets an untimely death, but then you get to control him as a ghost, joining the rest of the departed as spectres haunting the local hotel. Meanwhile, Dolores is an aspiring adventure game designer, who leaves behind her destiny as Chuck’s heir to work for the in-game equivalent of LucasArts. Like Maniac Mansion and Zak McCracken, you can switch between any of the characters once they’re introduced, and can act independently.

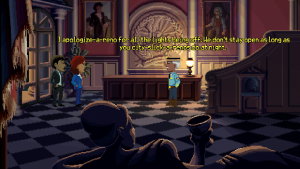

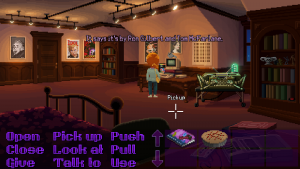

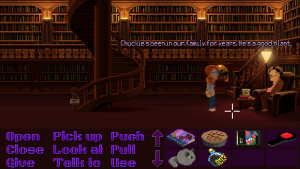

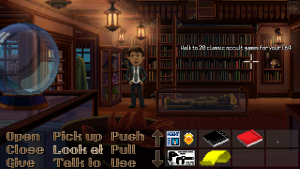

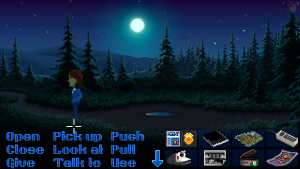

The characters are designed in the same style as Maniac Mansion, with large heads and skinny bodies, though they’re much more detailed than they were in the C64/DOS days, looking more like the Japan-only FM Towns release of Zak McKracken. The backgrounds relish in the low res pixel art look, but with a much larger palette than could be expressed with 256 color VGA. The interface, with its nine verbs and inventory icons, calls back to Monkey Island 2, and you can even enable an option that uses the classic fonts. You can run by double clicking or even by holding down the button and guiding your character, so moving around is quick. Early in the game you also get a map so you can move to all of the major locations easily. The status bar is also transparent, allowing for various foreground elements to be seen, like the toes of a corpse in the morgue. The entire game is also voice acted, all of it excellent. One quaint aspect from the old days is that, if you’re playing on a computer, you need to hit the period key to skip dialogue, rather than clicking through it.

The design is fairly open-ended. The first couple chapters give you almost free reign over the downtown area of Thimbleweed Park, with the rest of the game world opening up after you’ve obtained a map. Except for some major puzzle that open up new areas, most of them can be solved in any order by almost any of the characters – they don’t really have any specific skills, and for the most part, only ones that require a specific person do so for plot related reasons. In order to keep things straight, each character either has a notebook or a “to do” list that indicates all of their current quests and whether they’ve been completed or not. Ron Gilbert, on his Grumpy Gamer blog, has long stressed about the importance of puzzle design and how puzzles relate to each other, and Thimbleweed Park expertly puts those ideas into practice. It’s open enough that you have several different tasks at a given moment, but if you get stuck, you can wander around and try for another goal in the meantime. Simultaneously, it also sidesteps the “three trials” structure used in Monkey Island that has since become something of an overused trope. It’s not quite perfect, because some tasks technically do need to be completed before you can do others. Right at the beginning, you get the corpse’s hotel key card, and you’re supposed to check out his room. But you can’t actually do this until the third chapter.

Like the second and third Monkey Island games, there are two difficulty levels: Casual and Hard. Casual is definitely meant for the type of gamer that likes the exploration and dialogue portions of adventure games, but isn’t so fond of the puzzle solving. There are still puzzles, of course, but they’re often trivial, usually just revolving around being aware of the environment or calling certain phone numbers. It’s a good choice for folks who like walking around and talking to people, without the need to dig up a FAQ whenever you get stuck.

To contrast, Hard mode is definitely much closer to the early 90s LucasArts games in difficulty. For example, an early task with Dolores requires printer ink. In Casual mode, you just pick it up. In Hard mode, you have to go through the steps to make your own. Later on, you need a thimbleberry pie – in Casual mode, it just shows up in Dolores’ inventory but you need to bake it yourself on Hard. While the basic story is the same on both difficulty levels, Hard mode has a number of extra areas and a ton of extra scenarios that don’t appear in Casual mode, plus Casual mode has a whole bunch of superfluous items and a few subquests that don’t seem to lead anywhere. In other words, to get the full Thimbleweed Park experience, you definitely need to play on Hard mode.

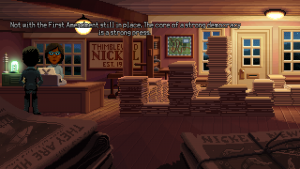

The key to the game is the weird people that inhabit the town. One of the first folks you meet are the Pigeon Brothers, a duo of plumbers who dress in pigeon costumes and seem to be unnaturally obsessed with unseen supernatural “signals” in the air. The sheriff also appears to do triple duty as the town coroner and hotel manager, each seeming identical outside of some quaintly obnoxious speech patterns. Some characters aren’t all that interesting but have amusing gimmicks with them, like the editor of the local newspaper, who lectures you on the various amendments of the US Constitution.

The dialogue has the same kind of snappiness of the early LucasArts games, that managed to keep conversations interesting without dragging on too long. Like the library in Monkey Island 2, there are a few areas you can just sit and muse at a number of goofy book titles, many provided by Kickstarter backers. Many backers have their name listed in the in-game phone book, complete with recorded message. (There’s also a meta joke about thousands of names being listed despite the population of the town being about 80 people.) There’s a even a subquest that literally involves pixel hunting, for little specs of dust pepped about the game world, an impractical task that rewards you with basically nothing.

The game is also filled with meta references to adventure gaming, as well as tons of allusions to Maniac Mansion (and to a lesser extent, Zac McKracken). It’s very clear that it takes place in the same universe – you can even find Dave and Sandy (his kidnapped girlfriend) working at the local diner, though the dialogue doesn’t really make any allusion to the events of the game. There are some references to Razor’s band, and one of the characters is even supposed to be Bernard’s relative. Chuck the Plant makes an appearance, and the library in the Edmond mansion has some of the same architectural quirks as the Edison’s (and there’s an amusing little puzzle that plays on adventure game logic that goes with it too). And in continuing a gag found in these games – one had a chainsaw with no gas, the other has gas but nothing to use it with – you can finally find both in the same game. On some level, you don’t really need to have played Maniac Mansion to get these jokes, because they’re still funny on their own, but it definitely expects you to have some working knowledge of the genre to really appreciate them. This is particularly true when playing as Dolores, who comments at some innocuous actions that would have killed her, had she been a protagonist in a Sierra adventure game. It all comes together at the ending, which certainly one ups Monkey Island 2 in its weirdness.

It’s not without its weaknesses though. The environmental observations are pretty bland, since most of them are identical across all of the characters, as are most of the conversations with the townspeople. Writing unique lines for each character may have been outside of the game’s scope but it still really been a really rewarding way of exploring the town with each character. The original release was a little weird in that main characters couldn’t really talk to each other, but the developers took criticism to heart and added extra dialogue in a patch.

Some areas are strangely empty – there are weird things that you’d think the characters would comment on, but there aren’t even any hot spots to interact with them. And even though the multiple player characters is one of the highlights of the game, most of the focus is on Dolores. Outside of some backstory and their general demeanor, there’s very little to differentiate Ray and Reyes, other than the fact that he’s amused by the town and she just wants to get out as soon as possible. Ransome’s gimmick is that he’s a huge asshole, which is a little amusing at first, but doesn’t really evolve on this throughout the game. In general, the humor, much like Gilbert’s other games, is much darker and weirder than the cartoonish goofiness of later LucasArts games, so it’s much more focused on bizarre scenarios and characters rather than laugh-out-loud dialogue, though there’s still plenty of great lines.

Gilbert has said that Thimbleweed Park isn’t meant to be how classic adventure games actually were, but how people remember them. Together with Maniac Mansion and Zak McKracken, it may as well be a third game in a trilogy that’s taken thirty years to be completed. (Day of the Tentacle, despite its high quality, doesn’t technically count in this respect, since Gilbert wasn’t involved.) It succeeds where Double Fine’s Broken Age faltered – it recalls the bygone era but with both improved visuals, owning to better technology, and better puzzle design, owing to three decades of progress. It easily earns its spot next to LucasArts’ classics.