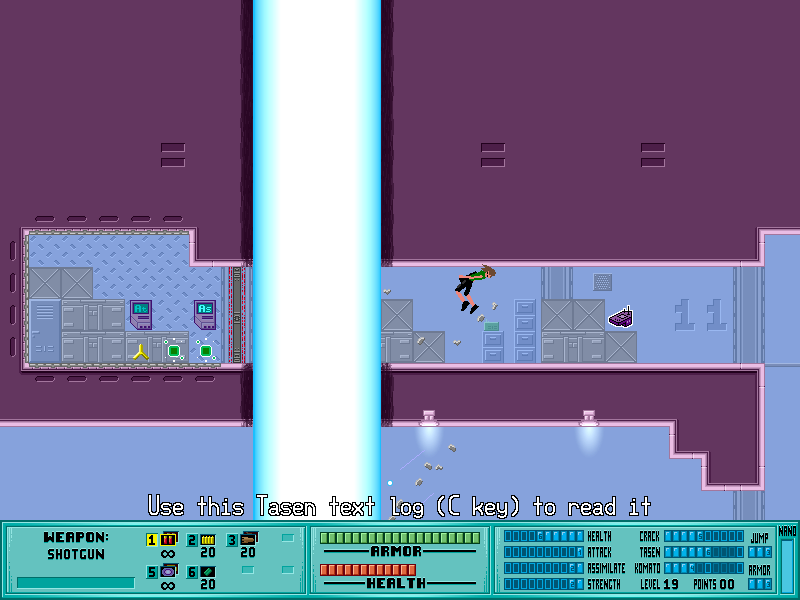

On the surface, Daniel Remar’s Iji may sound like a random collection of gaming and sci-fi cliches: it’s an independently made retro (although it goes for the Amiga style rather than the usual NES or SNES) platformer in which a nanomachine-powered cyborg fights her way through a military base invaded by hostile aliens while trying to save the world. Predictably, there are a lot of guns, quite a few boss fights and many explosions. And yet Iji is anything but typical.

There is depth in Iji despite what it might look like at first, and most of it comes from the introduction of something rarely seen in platform games: choice. Even more unusual though is the way this was implemented – choice in Iji is seamlessly integrated into its gameplay. The game doesn’t branch the story by making you pick an option from a menu, doesn’t make you decide by following different corridors and it almost doesn’t make anything depend on some cryptic actions you couldn’t have predicted. Instead of it, the game actually reacts in logical ways to the way you decide to play it.

In Iji, players take control of the eponymous character as she discovers that most of her family members are dead, she is trapped among alien invaders and also she’s the only one who can stop them as the surviving scientists have equipped her with reverse-engineered alien weaponry. Things are only going to get worse for her as she discovers the true extent of the invasion and is forced to confront progressively more powerful (in a both physical and political sense) enemies.

The game’s story is surprisingly long and complex for a platform game and there are quite a few plot twists along the way, the most important of them being the discovery that the attackers – the race known as Tasen – are at war with a ‘space peacekeeping force’ known as the Komato Empire. As the game’s characters don’t have hopes for reclaiming their planet through the use of one woman army, they decide to contact their enemy’s enemy in hopes of finding a powerful ally. It won’t be much of a spoiler to say that things don’t quite work in the humans’ favor.

The arrival of Komato forces might be the first time the players notice both the game’s great programming (as the aliens will fight each other, use different weapons and collect items that increase their health and experience) and the amount of moral ambiguity and nuance in its story. The Tasen might have invaded the Earth and caused deaths of millions but the Komato will do anything they can to ensure complete extermination of their age-old enemies – and they won’t hesitate to destroy humans in process. It’s not like either the Tasen or Komato are simply hordes of violent monsters as both races have their history and culture. They’re not monolithic either as you’ll encounter characters with different personalities, motivations and opinions (yes, it includes different opinions on the whole ‘violent invasion of the Earth’ thing).

Characters

Iji

The game’s protagonist – a girl equipped with reverse-engineered alien technology and tasked with ensuring the humanity’s survival. Just what kind of a character she is depends greatly on the player’s actions which shape her personality. Called ‘Human Anomaly’ by the aliens.

Dan

Iji’s brother who communicates with her through loudspeakers. After the invasion he decided to push his feelings aside and do everything that’s necessary to survive.

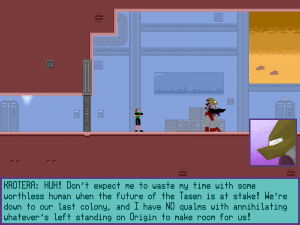

Krotera

Tasen Elite who seems to think that the extermination of humans is the only way Tasen can survive. Doesn’t have the best relationship with his subordinates.

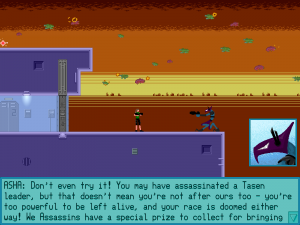

Asha

Strong but arrogant Komato Assassin. Initially wants to kill Iji to collect the bounty placed on her by the Komato millitary but after being defeated once starts treating her as a personal rival.

Iosa

Komato Annihilator known of her extreme hatred of Tasen. She has her reasons for this though as she was the only survivor of Tasen attack on her home planet.

Tor

Komato General, leader of the fleet fighting against Tasen on Earth. A reluctant warrior who isn’t too keen on exterminating Tasen and humans but doesn’t think it can be stopped without causing even more violence. His dialogs are some of the best in the game – a bitter examination of nature of political power and mob mentality.

As was said earlier, a lot of things in Iji depend on the player. This truly is a mixture of platformer and RPG – and the RPG elements go beyond the usual levelling and stats distribution (which is still present) as you really play the role of Iji and shape her with your actions. If you fail to save a certain character, she’ll suffer a mental breakdown and go nearly insane, not being able to accept the truth. If you fight a lot she’ll become desensitized towards violence – but if you go all the way and slaughter everything in your sight she’ll even start enjoying the bloodshed.

Many things in the game depend on your kill count which serves as a sort of karma system. It never feels forced though: it’s pretty reasonable that some of the Tasen soldiers will propose a truce if they don’t think of you as a threat (especially when some of those soldiers are known to oppose Krotera’s idea of human genocide) and that even some of the militaristic Komato are able to admire your idealism. It’s a very well thought-out system – and that’s also why it’s a shame that there is one enemy whose death can only be avoided in an extremely counter-intuitive way (you need to max out your Tasen and Komato skills to use the aliens’ best weapons and max out your Crack skill to combine them into something that can shoot through the walls of Sector X reactor; there’s a lot of grinding required and as you’re trying to be a pacifist it means hanging around battlefields and waiting for the enemies to kill each other).

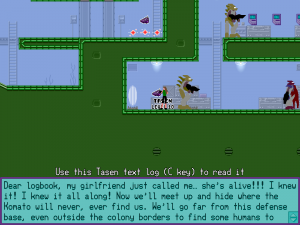

There’s a lot of subtle changes depending on your playstyle that you might not even notice if you don’t play Iji more than one time using different approaches. Probably the most interesting one is that the game keeps track of one of the unnamed Tasen soldiers in Sector 3. Some of the logbooks you’ll find in the later sectors detail her relationship with a different soldier and they’ll change drastically depending on her being killed or surviving.

The logbooks are interesting too as they reveal a lot about the backstories of all the races, some of the characters and even the Earth itself (it’s called Origin by the Komato who lived there before humans but abandoned it during the expansion of their empire). Some of them, like ones mentioned in the previous paragraph, describe various characters’ reactions to the current events and as such will change depending on how you play the game. The same goes for dialogs – there’s a lot of detail put in there to ensure that gameplay and story are intertwined and your choices matter.

Iji is clearly inspired by both cinematic platformer games and the Metroidvanias. The former are the most obvious in the game’s visual with their vectorized design and fluid animation reminiscent of Another World’s use of rotoscopy. The latter shows up in the way the levels – or Sectors, as they’re called in-game – are designed: large, non-linear (despite having one entrance and one exit), requiring puzzle-solving and use of acquired weapons and skills. On the other hand, Iji isn’t as heavy on instant death traps (there generally aren’t too many ways to die other than HP loss) as other cinematic platformers and, unlike most metroidvanias, is divided into separate levels instead of giving you the ability to backtrack to anywhere.

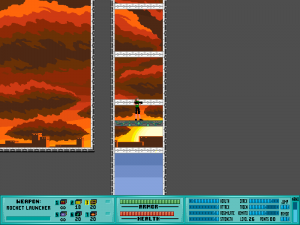

The level design is generally speaking great as it allows progress with the use of different skills (kicking down doors, cracking, fighting) while still occasionally railroading the player in non-obvious ways into scripted setpieces like giant battles between Tasen and Komato or a powerful beam fired from the spaceship destroying the ceiling. It never feels boring or repetitive, especially with added attractions like ridable vehicles or a short trip to the Komato ship.

What does feel repetitive are the bland looking (except in the outdoors sections with spaceships hovering – and later fighting – in the sky) backgrounds. Sure, they are instantly distinguishable from the foreground which avoid a common problem in platofrm games – too bad they’re boring and simply not memorable. Still, the great character designs make up for it and Iji’s overall look is far from bad.

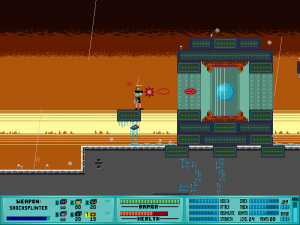

The basic gameplay of Iji is pretty simple: walking through the level, fighting (or avoiding) the enemies and upgrading your stats. The latter works in a predictable way – get experience points (glowing balls of ‘nano’ left by the dead enemies – they drop it regardless if you’re the one who killed them so make sure to hang around the battlefields) until you see the ‘level up’ message, then upgrade the desired stat in one of the upgrade stations (they’re generally easy to find in every Sector). Stats themselves don’t work in the usual way – most of them (with the exception of health, attack and assimilation) don’t increase the effectiveness of certain actions but simply make them possible to perform on more difficult targets (e.g. kicking down bigger door or cracking for more powerful weapons). It’s a design choice not everyone will like but it’s there for a reason – it makes sure that grinding for stats won’t make the game too easy (also, the levels are laid out so that you won’t get stuck even if you lack certain stats – the only exception here is the aforementioned perfect pacifist run).

Several sectors as well as the game as a whole end with a boss fight. Most of the bosses are of the tricky variety in which the pure firepower approach is not the most reliable one – they’ll either be invulnerable to certain weapons or simply have a lot of health, requiring you to utilize features of the boss area. Still, well prepared player will be able to take most of them down with big guns if he brings a lot of ammo (maxing out the assimilation stats will be helpful in this department). The game’s final boss is mostly an endurance match though as the most reliable way of defeating him is by avoiding most of his attacks and reflecting the strongest one back at him. It’s a good challenge – and if you find him too easy the first time, there is an option of making him even more powerful on subsequent runs.

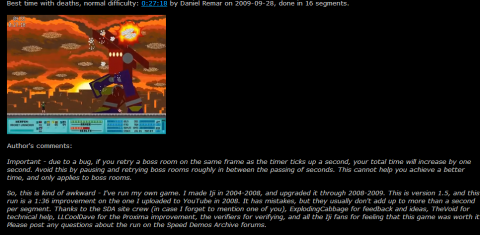

On normal difficulty level and if not doing a pacifist run, Iji is not too difficult (fortunately, it’s not a walk in the park either – it provides challenge without being too unwelcoming to the newcomers). There is enough replay value (game reacting to different playstyles, secrets, hidden Sectors) here though that many players will want to challenge themselves by playing it on hard, extreme or the unloackable ultimortal difficulty. The last one is almost unfair (the added time limits are very strict) but it’s possible – unlike the hidden ‘reallyjoel’s dad’ (named after a YouTube commenter whose father was supposedly extremely skilled at video games) in which the first Sector is intentionally unbeatable. And if the harder difficulty levels are not enough for you, the game was designed with speedrunning in mind – the current record on normal difficulty even belongs to Daniel Remar himself.

Iji features an awesome heavy metal soundtrack (downloading an optional high quality version from the creator’s website is definitely a good idea). The music is fast-paced, energetic and aggressive. The best of those tracks – and the one used in the game’s trailer – is definitely the final boss theme which really makes the player pumped for the battle. Several slower and quieter songs are used during the cutscenes. There’s also one vocal song – Lifeforce’s cover of VNV Nation’s Further. It plays during the game’s ending and it really fits its bittersweet, uncertain mood.

There are sound effects in Iji but (as is often the case with sound effects) there’s not much that can be said about them. They work and that’s it. The game also features a bit of voice acting which is really good (especially with the protagonist whose personality changes are actually reflected in her voice) and it’s a shame that most of it is just battle cries and screams of pain.

Iji works in an 800×600 resolution, although the images used during cutscenes are smaller so big parts of the screen are left unused at those times. The game was developed in Game Maker and because of the way the engine handles the objects it may suffer slowdown on older computers during the more intense battles (especially the final boss fight). Interestingly, the game was actually programmed to detect those slowdowns and automatically reduce details if they get out of hand. It’s a neat little trick, even though it doesn’t work perfectly. The game is generally bug-free (there is a small issue regarding timer if you die to a boss but that’s only of interest to speedrunners). Iji hasn’t been ported to anything other than Windows but it was translated into Chinese and Korean.

Iji is a unique game made of generic parts (the gameplay is a blend of metroidvania and a cinematic platformer, the plot of aliens invading the Earth to escape from even more dangerous aliens is quite reminiscent of the Half Life series, Daniel Remar himself thinks of the game as a 2D spiritual successor to the System Shock series etc.), great attention to detail (from the cameras moving in the background depending on who is actually controlling them at the moment to the final boss having a sort of adaptive AI) and an easily identifiable visual style. It’s also a solid, well-designed and well-programmed title.

The game’s strongest advantage over its competition (and there was a lot of it before the main indie trend changed from retro platformers to a more broadly defined category of games with roguelike elements) is definitely how it integrates gameplay and story. There’s a lot of non-linearity in Iji – from the protagonist’s mental state to the fate of Tasen race – and it all depends on how the player approaches the game. While many things depend on what is basically a karma meter, the game manages to make it all seem logical. This is as natural and seamless as it gets, at least in an action game where a bulk of plot is revealed by reading logbooks.

That is not to say that Iji is completely without problems. Many players will find the pacifist message a bit heavy handed while the others might have issues with actually playing the game as a pacifist given that Iji actually takes damage from touching the enemies (and they can’t always be avoided given the game’s two-dimensional nature). Still, the issues are generally minor compared to the game’s merits. After all, it’s simply a good game.

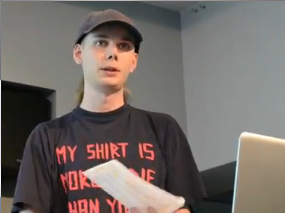

Iji is clever, well made and fun to play. It’s also a great examples for aspiring developers as it demonstrates what can be done with storytelling in a platformer and how to integrate gameplay and storyline as well as showing some very good level design. It’s also an example of what can be achieved if the authors take time to polish their game as opposed to rushing the release (which often results in unfinished and buggy titles) – Daniel Remar started working on Iji in 2004, released it in 2008 and kept updating it until 2010.

Links:

Iji on Daniel’s base – official website; contains game download, translations, walkthrough and a soundtrack

Official trailer

Iji on Speed Demos Archive – Daniel Remar’s speedrun of his own game

Iji on TIGSource – a writeup by Derek Yu, creator of Eternal Daughter and Spelunky

Unofficial walkthrough on Strategy Wiki – helpful for those attempting the perfect pacifist run