To explain Grandia, you have to begin with Lunar.

In 1992, Game Arts, a Japanese video game publisher and developer established in 1985, released Lunar: The Silver Star for the Sega CD. It was an attempt to create a role-playing game with a greater focus on storytelling and worldbuilding than previously seen in the genre, with developers paying particular attention to crafting an elaborate mythology for its setting and characters with rich personalities.

Though not a genre heavyweight these days, Lunar made waves in the role-playing community in no small part due to this focus on its world and characters. Lunar would go on to receive enhanced ports for the PlayStation, the Game Boy Advance and the PlayStation Portable, and a sequel, 1994’s Eternal Blue, which received its own enhanced PlayStation port in 1998.

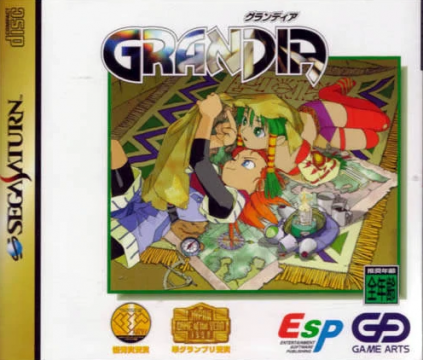

Aside from the sequel and re-releases (and the poorly received, best ignored DS title Lunar: Dragon Song in 2005), Game Arts moved on from creating new Lunar games after Eternal Blue and focused on a new property that would closely follow its development philosophy. Game Arts first released this spiritual successor in 1997 in Japan for the Sega Saturn. It was called Grandia.

Grandia would go on to spawn a franchise with more original titles than Lunar: Two sequels, two spinoffs, an online game that ran for about three years, and a disc of bonus content for the original game.

Though arguably peaking after the second main game and never reaching the success of other, similar series, neither abroad nor in its home country, Grandia is an altogether charming series with an iconic core battle system, engagingly interactive worlds, and an influence that is still felt, however indirectly, in the JRPG canon to this day.

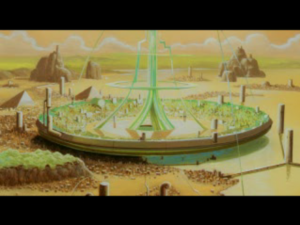

Grandia centers on Justin, the young rambunctious son of a great explorer. Justin lives in Parm, a port town in a world in the midst of an industrial revolution, and dreams of going out on wild adventures himself some day. That dream becomes reality when, while investigating a ruin of the ancient Angelou civilization, he sees a hologram of a woman named Liete. The hologram tells him to travel to a lost city beyond the edge of the world called Alent, where she resides and where he can learn what happened to the Angelou.

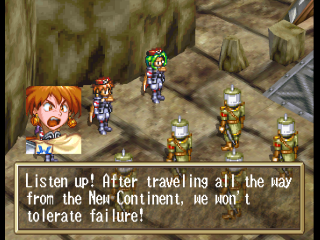

Meanwhile, the Garyle Forces, a private military and the main antagonists for much of the game, is seeking the knowledge of the Angelou. Justin and his friends at turns avoid and confront the organization as they travel across continents and beyond the known edge of the world, which is cordoned off by an enormous, seemingly insurmountable stone wall, in their quest to find Alent.

Characters

Justin

A young boy seeking adventure like his father and grandfather before him. Brash and impulsive, but kind and fiercely protective of his friends. Justin carries a strong moral core that becomes more and more evident as the plot moves from lighthearted to serious. Uses swords, maces and axes.

Sue

An energetic girl who wavers between Justin’s voice of reason and his partner-in-crime. Accompanies by her pet creature Puffy, a white ball with big eyes and rabbit ears who she uses for special skills in battle. Uses maces and projectiles.

Feena

A famous professional adventuress. She initially dismisses Justin and Sue as amateurs, but later events lead her to become more free-spirited and join them. The slow-developing romance between her and Justin is better written than most JRPG love stories. Uses knives and whips.

Gadwin

A powerful, stoic warrior with a philosophical nature who becomes a father figure to Justin. Extremely protective of his home village, Dight. The powerhouse character in battle by far. Uses swords exclusively.

Liete

The mysterious girl who appears in a projection to Justin and Sue, kicking off their whole adventure. A kind-hearted priestess. Uses staves exclusively.

Rapp

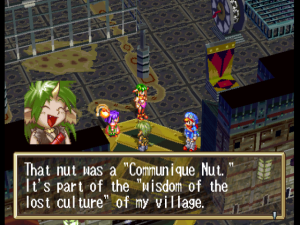

A Cafunian, which is a beast-like humanoid race with long pointy ears. A youth whose rude and arrogant nature masks hidden sorrows. Uses knives, shuriken and swords.

Milda

A Lainian, another beast-like humanoid race. The females are muscular and short-tempered and males look humanoid as children and transform into bipedal bulls as adults. Milda is hot-tempered and seeks revenge for the destruction of her home village. When not in a fury she can have a bubbly, doting personality. Uses swords, maces and axes.

Guido A worldly mogay, or talking rabbit, who works as a traveling salesman. He meets the party frequently over the course of the game before joining. Uses knives, swords and projectiles.

For better or worse, Grandia’s story is ploddingly paced. Many critical details about the main characters and the setting are presented in the first half and only make incremental developments in the plot itself until much later. For the most part it is a lighthearted adventure, with cliche dungeons (the series in general has a particular penchant for ancient ruins, which are at least thematically relevant) and silly means of getting sidetracked, like when a protagonist is kidnapped by a pea-brained young guild leader. The first half is almost entirely played with a party of Justin, Sue and Feena, even though four characters can fight in battle at a time. The majority of playable characters don’t even join you until over halfway through, which, in a 40+ hour long game, gives it a lopsided feeling.

That said, like Lunar, the character interactions are some of the best parts of Grandia. Some of the strongest dialogue comes from optional or tangential scenes, like the ones that occur when camping or having a meal together in which Justin talks to each character in turn as they discuss their lives and their predicaments. This feature goes on to become a series tradition similar to the skits of the Tales series. Even NPCs are more lively than the usual fare, subverting the “Welcome to Corneria!” trope with most having full conversations with Justin that change each time you talk to them as you progress. Sequels also honor this attention to detail.

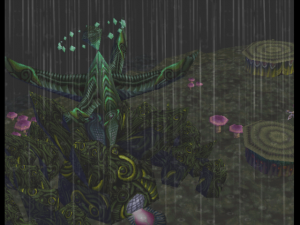

The setting has a strong foundation as well. The developers made a conscious effort to establish a post-Age of Discovery world, with a culture steeped in the forward momentum of industrial capitalism, technological advancement and the accrual of resources. It takes a very long time to pay off, but all this context enriches the main storyline once the game gets around to actually dealing with it. Without giving too much away, it becomes clear that the Angelou civilization paid dearly for its sophisticated technological prowess, and modern society is at risk of suffering the same fate.

Despite how overdone the ancient, technologically-advanced civilization is in JRPGs, the trope is done well in Grandia. More than that, Grandia as a series focuses so much on the archaeological exploration of ancient societies that it really makes the trope into its own thing. In fact, as played out in the first game, Grandia nicely complements Wild ARMs’ environmentalist themes with a message of healthy apprehension toward the over-exploitation of technology and limited resources.

Graphically, Grandia is a fully 3D polygonal world with character sprites, much like Xenogears, Breath of Fire 4, and Wild Arms 2. Palette-wise, it is much brighter and varied than those three, but the visuals have aged somewhat more poorly because sometimes the game is painted to the point of gaudiness. The patterns and colors of certain environments clash and are sometimes headache-inducingly vibrant.

The graphics aren’t helped by Grandia’s navigation problem. Early 360 degree camera games all had some problems with keeping the player orientated on the map, but it is especially bad here. Particularly in dungeons, which are long, labyrinthine and often do little to differentiate one area from the next visually. It can get so disorientating that there are literal waypoints dotting most of the bigger environments to temporarily zoom the camera out to a bird’s eye view, offering a broader glimpse of your nearby surroundings. This shows that the developers were aware of the problem, but tried to put a band-aid on it instead of reducing the scope of the dungeons or adding visually unique characteristics to each area to make them easier to work your way through.

That said, aside from navigation, the rest of the game isn’t difficult or complicated. The overworld is a simple map screen with travel options, eschewing a world map. You’re rarely offered access to more than a couple locations at a time. The dungeons, for all the confusion that their sprawling, identical-looking corridors cause, are typically just a matter of scrounging around for switches to open locked doors or reveal hidden pathways. There are no random encounters and monsters are shown on the map, which is nice. While they are still numerous enough to be unavoidable more often than not, they aren’t usually overbearing either.

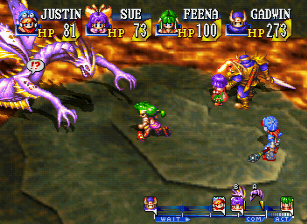

The battle system is one of Grandia’s most notable features. Turn-based with light real-time elements, its defining feature is the Initiative Bar, later dubbed the IP Gauge, which determines when combatants can attack. Each combatant has an icon that moves along the bar, its speed determined by a character’s IP, or initiative points. An icon first moves across the “Wait” period, during which nothing happens, until it hits the “Command” or “Action” point. Here the player or the enemy chooses an action like a normal turn-based battle. Actions aren’t fulfilled immediately after selecting them, however. There is a period between selecting an action and actually carrying it out, and this is where the most engaging and fun strategizing comes into play.

One of the big gambits in Grandia is that this grace period can be exploited to counter and even cancel enemy actions if you attack at the right time. Each character has two attack options: Combo or Critical. Combo tends to deliver more damage, but Critical can cancel an action. Magic and skills can also accomplish this, but they take longer to perform. The trouble is the enemy can do the same to you. Battles then become a struggle to ensure characters are protected during the action grace period and, in response, to delay enemies by attacking when they are in their own grace period. It’s all very satisfying to watch too, with chaotic action that pauses dramatically as the game awaits input. Enemies explode satisfyingly into little polygons when slain.

Like Lunar before it, Grandia emphasizes the location of characters and enemies on the field. It isn’t free-roaming like a Tales or Star Ocean game, but your characters will run around the field depending on who they target and what actions they take, making it important to strategize who to attack first. You can also move them voluntarily with the defense command. Sometimes characters will give up carrying out a physical attack if the enemy is too far away. A few magic spells and skills are line-, range- or area-based too. These features become more integral in the sequels.

Character growth is determined by experience points as usual, but in addition to standard character leveling up, characters also level up their magic, skills and weapon types. Justin, for example, uses swords and axes. As he gains proficiency with either weapon type by using them more often, certain stats increase and new skills open up. Magic, too, is used to gain stat bonuses and more skills. As leveling up characters happens slowly, leveling up these sub-categories is important to keep ahead of the difficulty curve.

Characters learn magic by first finding Mana Eggs, which are scattered throughout the game, and using each for magic in one of four base elements: Fire, Wind, Water, and Earth. From there, the elements can converge after certain magic level thresholds, resulting in Forest, Blizzard, Explosion and Lightning elemental spells. Weapon and magic levels also intertwine, with some skills needing an amount of experience in a certain magic as well as weapon level before they can be unlocked.

Grandia is infamous among the very niche community of people who study JRPG menu interface. Put simply: The menu is bad. Plain ugly. The game’s title streams across the screen constantly in the background for some reason. It takes too long to open up. It is burdened with unnecessary blocks like limited inventories for each character and sub-menus that could have been better streamlined. At the same time though, it does display helpful information about your progress, letting you know what the criteria is for the next closest skill or magic to learn, which helps you figure out which kinds of weapons and magic to prioritize.

The music is composed by Noriyuki Iwadare, who composed the soundtracks for the Lunar games and who later composed all the sequel soundtracks. Some of the tracks are performed with a live orchestra, including the stirring orchestral fanfare, which is unusual for RPGs of this era. However, most of the game’s tracks are played using the PlayStation sound chip. The lesser tracks suffer from some repetition, but the instrument choices are interesting: Chimes, wood block, bagpipes, accordion, french horn, etc. They often give the impression of steam, hammers, physical labor, in particular the “Town of Parm” song, contributing to the rapidly industrializing feel of the world. But the battle themes in particular are stellar, with two main battle themes depending on if you ambush the enemies.

Though overlong and cumbersome even by the standards of 1999, Grandia is not only playable but still delightful today. The story is light but has a strong setting, and it is grounded with wonderful character dynamics.Its battle system manages to be fast-paced and engaging within its ultimately turn-based format, offering a rough version of the excellent variations the sequels would develop. In fact, Grandia introduces almost all the features – the battle system, the character growth (both in writing and mechanics), the depth of worldbuilding – that would be ironed out and refined in the next installment in the franchise.

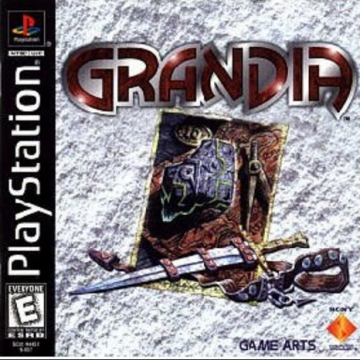

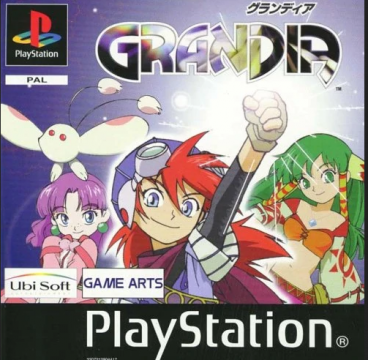

When it initially came out for the Sega Saturn, the first Grandia was met with acclaim in Japan and gained interest in English-language gaming circles before it was localized. But didn’t receive an English localization until it was ported to the PlayStation in 1999. The localization was made by Sony itself. Compared to the boisterous Lunar localizations from Working Designs, the writing in this version is a bit drab, though not terrible. The voice acting quality is a little more mixed, though.

The port itself changed little, but there are some technical downgrades – missing shadows, less textures, missing effects, and so forth. They aren’t noticeable without comparing them side-by-side, but those who have played both versions will probably see some things missing. The Saturn version already suffered from slowdown (especially when running through towns) and issues like that still appear in the PlayStation version. The battle backgrounds are also a curiously low resolution 2D bitmaps in both versions, which look particularly bad whenever the camera scales in. The two year delay meant that some mechanics, most apparent in its cumbersome menu system and bland dungeon design, aged poorly, but others remained remarkably fresh for players of the time.

In 2019, GungHo Online Entertainment released Grandia HD Remaster for the PC and Nintendo Switch. It uses the PlayStation code (and purportedly takes some assets from the Saturn version), then adds graphical filters to the sprites, textures and interface. The result isn’t as successful as Grandia II HD, as sprites and text boxes are overly-smoothed and look too polished and somewhat out of place against the still-blocky polygonal environments. However, the widescreen support and customizable resolutions for the PC version, and the general ease of access on modern platforms make the best version to check out.

In 1998, an expansion for Grandia called Digital Museum was released for the Sega Saturn in Japan exclusively. More a fan service package than a sequel, Digital Museum sees Justin, Feena, and Sue being teleported by Liete to a museum honoring their exploits in the original game.

The exhibits go missing, however, and the party has to explore dungeons from the first game to find and restore them. This busywork unlocks bonus material like music, sounds, artwork, storyboards, character portraits, a bestiary, minigames, cutscene clips and a set of save files to use in the original game.