Sexuality and violence are the norm in popular current-gen video games, but the intention is commercial rather than artistic. Sillier than mature and more empty than meaningful, those games are essentially attempts to appeal to gamers’ base pleasures, to give them the chance to absorb themselves in satisfying albeit inane carnage; bikini-wearing girls and muscled army men shooting big guns to kill generic enemies through bland environments.

But sexuality and violence don’t have to be such superficial themes. Exploitation might be tantamount to desensitization, but there can be reason and merit behind this. Sexuality and violence were favorite themes of renowned literary figures such as Anthony Burgess and the Marquis de Sade. They explore and explain our fascination with this primal fetishism, argue that they exist for more than simple marketing tactics. Because although many video games use them for capital gain, others may use them for, y’know, aesthetically pleasing purposes: art, expression, etc. Silent Hill 2 is a glorious example. Dark Seed, I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, and Dreamweb also spring to mind. Independent adventure game developer Harvester Games, which is led almost entirely by Remigiusz Michalski, created another entry into this highly laudable category: Downfall.

The bulk of the indie adventure game scene is neither pretty nor polished nor creative nor really worth much of your time, but once in a while somebody uses Chris Jones’ Adventure Game Studio for something spectacular, a game any lover of the genre shouldn’t miss, and Downfall is one of them. While not without its flaws, it’s a promising first effort. Along with other indie developers such as Wadjet Eye Games, Harvester proves itself another promising figure for the future of independent video game production.

Downfall is the product of Michalski getting tired of playing The Secret of Monkey Island, reading too many horror books as a child, and seeing gross, disturbing things while working at a home for the old and mentally ill. His goal was to make a really mature game, one that really bites players on psychological level. (Amusingly, Steam rejected Downfall from being sold in its stores due to its controversial content.) He also stated his dissatisfaction with how easy modern adventure games are and that he wished to make something unique while still going back to the genre’s roots.’

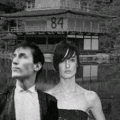

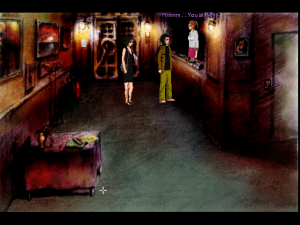

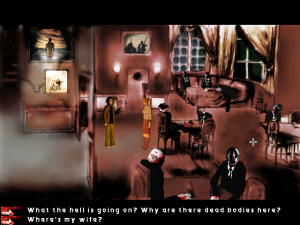

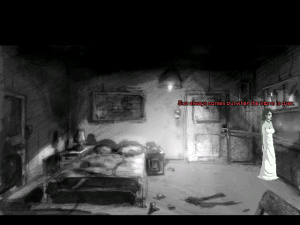

The story concerns Joe and Ivy, who together reach a small town on a stormy night looking for a room for the night. They take shelter in Quiet Haven Hotel. Things go off the deep end almost immediately. (Almost too fast if you want to get fussy.) After having an argument about their rocky marriage, Ivy disappears. What’s more, the hotel has transformed into a gruesome shadow of itself: Rooms covered with debris and carnage, blood coating the walls, even a dining room full of faceless corpses.

Characters

Joe Davis

A troubled young man with a troubled marriage. He is stubbornly determined to keep things “the way they were,” attached to a past that may not have ever existed. His need to patch things up makes for an ideal adventure hero. He has a one-track mind, especially in regards to finding his wife, and is thus very much willing to trudge through the horrors of the hotel as long as it means reaching his goal. Choices made by the player heavily affect his character development.

Ivy Davis

Joe’s wife. She begins the game spouting hellish nonsense, piecing together imagery of blood and death and insanity. (This dialogue, as it happens, was in part lifted from some of the elders Michalski took care of.) She then promptly disappears. Though on screen for only a brief time, Ivy is an important figure to keep in mind.

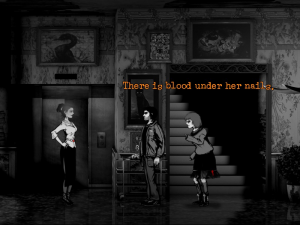

Agnes

Joe’s “sidekick” and for all intents and purposes his foil. Agnes is awakened on the night before her wedding by the ghost of her favorite rock star in order to help Joe. Convinced she is dreaming, she’s not fazed much by the horrors going on about town, though she’ll still cover her eyes whenever you’re in a room with corpses. Like Ivy, her purpose is much more integral to the plot than things appear. The name “Agnes” is also begrudgingly shared by Michalski’s real-life partner.

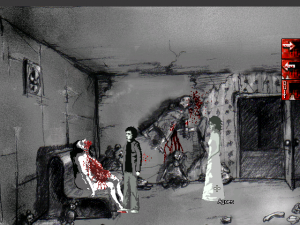

Joe learns from the hotel’s receptionist that his wife has been taken by a woman named Sophie. Exploring the hotel, Joe encounters Sophie in her many forms; or memories, more like. She is a crying child, a woe-begotten woman at a party, an obese sack of flesh in the bathtub, and so on. Joe’s journey involves murdering these incarnations if he is ever to see his wife again. This sadistic edge desensitizes the players to brutish violence as much as Joe.

The game has three vastly contrasting endings. It is also generous enough to allow the players to see all three without much backtracking. The story, when things come full circle, is a mixed bag. It is multi-faceted and layered, but at first glance one can get the impression that it falls too heavily on horror tropes. This is of course pure opinion and up to player interpretation. Michalski himself describes Downfall as a deeply personal game. What this entails precisely is unclear, but the game does certainly touch upon subjects that normally don’t get attention in the mainstream: Eating disorders, insanity, broken relationships, sadism, and child abuse to name a few. They’re presented with no punches pulled. If nothing else, Downfall challenges players ceaselessly with its unapologetic presentation.

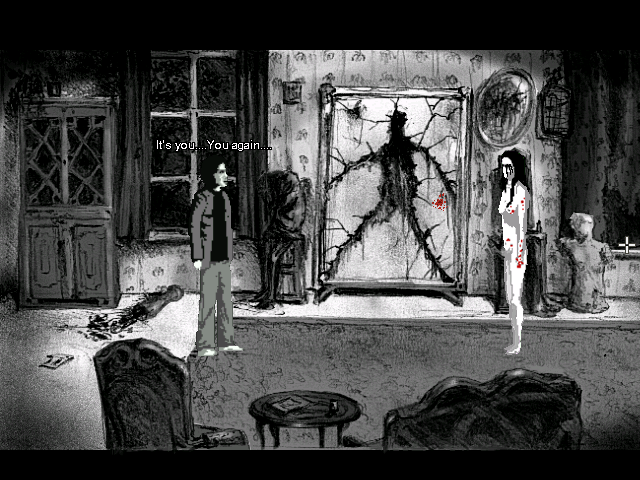

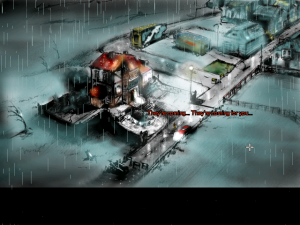

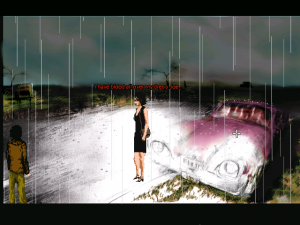

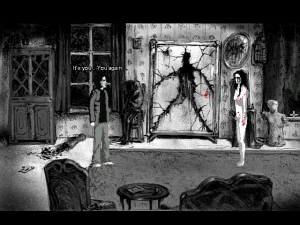

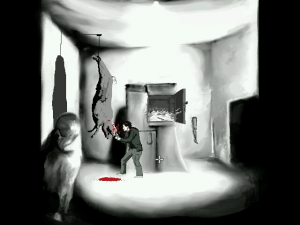

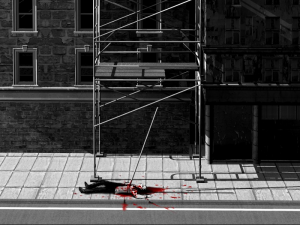

Graphically Downfall exceeds expectations. It has a sense of gritty style all its own, intermittently fading from color to black-and-white and splotched with blood. The look of the Quiet Haven Hotel is influenced by the nursing home Michalski worked at during the game’s creation. Not so much the blood and guts, but more so the sense of unease and disquiet, like something is making noises you can’t explain, the knowledge that dozens of people have died here keeping you on edge. The hand-drawn, low res (640×480, 32-bit) graphical style is lovely to behold. It has a skewed retro feel, in that essentially the style is reminiscent of old adventure games, but there are things happening on screen that would never happen in old adventure games.

Character designs are solid. They look like the characters one might find in a 2D Silent Hill. They are regrettably marred by choppy animation. (And doesn’t Ivy look way too much like she’s wearing a masquerade mask? Intentional?) But one must make allowances for minor flaws in independent games and this is one of them. Every character has a distinct appearance. Even the minor roles drip with personality, like the crazed neo-Nazi Doctor Z or the seductress hotel receptionist (whose corpse you discover hanging from the ceiling in her room). The cast is small but effective. The cadavers and monsters are wonderfully horrifying. While sometimes absurd, they never detract from the game’s overall style and atmosphere.

Gameplay is always the crux of adventure games. Downfall, noble a title as it is as a whole, falls behind in this respect. There’s just a jaggedness to most things. Take the inventory system, which will occasionally lock up for no reason. While easily worked around, it’s one of those curious glitches that deter from the experience. A few red herrings are tossed about as well, including a suspicious door labeled 666.

The puzzles themselves can be challenging though not unmanageable. One concerning a brainless cadaver is pretty difficult given a lack of guidance. (Just keep in mind scares can double as hints.) Many items also don’t disappear from your inventory when you’re done with them, meaning lots of clutter and confusion in item-based puzzles. Nonetheless you have to hand it to Michalski: None of the puzzles are arbitrary. They fit into the story and setting without complaint or question.

While most gameplay flaws can be overlooked, the most unforgivable is the boss battle near the end of the game. The point-and-click genre continues to develop more and more bad obtuse combat systems into their gameplay. Luckily here it’s over very quickly. While not game breaking or even terribly annoying, the problem here is that the combat comes off as stilted and silly when it’s supposed to be a pivotal moment in the story.

Downfall‘s soundtrack is composed by Remi Michalski’s brother Michal. It is an eclectic mix ranging from Akira Yamaoka-esque ambiance to porn groove. The aim was to recreate the feeling of electronic music found in B-movies, but ended up more reminiscent of Angelo Badalamenti’s soundtrack to Twin Peaks or the tracks found in George Romero’s movies. The effect is sometimes a bit silly, but always suitable. The music is an integral part to the game’s unique atmosphere. Very cool, very bizarre, very creepy.

The problem with independent video games is simple: Is it worth spending money on? Downfall costs $10. All things considered, its flaws and strengths and ambitions noted, Downfall is worth coughing up a few dollars. The important thing is that it was created out of love, not for a profit. Michalski created a game for a very select audience in a genre that appeals to a small fanbase in the first place. Little aspects of the game show a true creator-player connection, like the bookshelf in Doctor Z’s room. It isn’t very long, it’s far from perfect, it can be jagged and gawky, but it is ceaselessly unique; even, in its morose way, endearing. And as far as artistic video games are concerned, it’s important for the player to support their developers.

Harvester Games is currently working on their next project: The Cat Lady. Michalski has stated that the game will probably be even more gruesome than its predecessor. As of yet the release date is unknown.

Links:

Harvest Games Website

Slowdown Interview with Remi Michalski

Hardy Dev Interview with Remi Michalski

Adventure Classic Gaming Interview with Remi Michalski

Hardy Dev Review of Downfall

Slowdown Review of Downfall

Downfall: Redux – Windows (2016)

In February 2016, Harvester Games released a remake of Downfall. Reimagined in The Cat Lady format, the game is now presented at a side-scroller point-of-view and uses the keyboard exclusively. While the remake follows the same general narrative as the original, the script, the graphics, the music and the mechanics have been entirely reworked from the ground up.

In an interview with Alternative Magazine Online, developer Remigiusz Michalski explained his motivation behind the remaking:

“I’ve learned so much in the post-Downfall years that I knew exactly how to take this raw, immature (but in some ways promising) kind of mess and shape it into a decent game. One that will proudly sit beside The Cat Lady. […] So, out with the cheesy stuff, cranking up the horror to 11, removing the god-awful boss battle, explaining the characters better, redoing everything from scratch ? that was the plan.”

Joe Davis’s descent into a demonic hotel that would put the Overlook to shame is still often off-the-walls crazy, but the writing is much stronger this time. The tension between Joe and Ivy as they deal with their struggling marriage is much clearer to the player?Joe sympathetic but increasingly frustrated, Ivy troubled by her demons yet self-defeating and distant. Both are much more dynamic and better-realized characters. Ivy in particular, who was little more than a messed up damsel in the original, has become a fine character in her own right. Joe’s guilt-ridden past and the reasons for his troubled marriage with Ivy are clarified in far more detail. Agnes, an anomaly in the first game, is a fantastic character in this version, her presence actually necessary rather than a weird side-note. Joe and the various inhabitants of Quiet Haven Hotel are, in short, far superior to their counterparts in the original.

One of the biggest issues with the original’s story was its relative immaturity. While it certainly tried to create something thoughtful and deep vis-a-vis explicit sexuality and violence, it usually couldn’t help itself from falling into schlock territory. The Cat Lady subverted this flaw and created a rich, contemplative study of depression while brilliantly still allowing for 80s slasher film-tier gory abandon. While the Downfall remake does occasionally spiral into gory nonsense in ways that The Cat Lady managed to avoid, the story is treated with much more pathos and maturity than the original.

Now, Downfall is a tricky beast by nature. It is intentionally fragmented and crazy, a psychotrip through oft-random nightmarish visions. Though The Cat Lady and Downfall share this brand of twisted imagery, in the former the strength of those visuals relied on their relation to the protagonist Susan?they made sense, added to her development as a character and to the game’s sick, dreary atmosphere in general. Downfall succeeds in this only sometimes. While the various mutilated manifestations of Ivy scattered throughout the game are gruesomely on-point, other instances, such as when you accidentally immolate a cat, are childish at worst and superfluous at best.

The Downfall remake retcons references to The Cat Lady. Some are good, some are bad. The Queen of Maggots reappears, which is a fantastic way of melding the mythologies of both games?the creepy, omnipresent deity hopefully returns in Lorelai, Michalski’s next game, which would make for a great, unsettling link between each thinly connected narrative. Susan and Mitzi make a mostly unnecessary appearance, though, in a scene that only confuses the main story. Much like Joe’s appearance in The Cat Lady, in fact.

Having multiple, extremely different endings can sometimes sour the experience of playing a game. Because in order for the writing to be effective, it can’t simply diverge at the very end. (Looking at you, Mass Effect 3.) There should be build-up to each ending, suggestions of things to come. Take Wadjet Eye Games’s Shardlight – while a great experience, the multiple endings can be frustrating. The protagonist Amy has to make a difficult choice at the end of the game, and instead of allowing the player to decide what kind of person Amy is throughout the game via dialogue options, the developers created a personality for her that was flexible enough for each choice to make sense. This essentially sacrificed Amy’s character development in lieu of a single, albeit important, narrative branch. It feels like a wasted opportunity. Downfall curbs this issue by making Joe Davis’s personality very much up to player choice from the beginning. You can make him an asshole, a conflicted but caring husband, a tortured coward, etc. Thus each ending feels like you have been moving toward it throughout the whole game rather than something that just branches off at the very end.

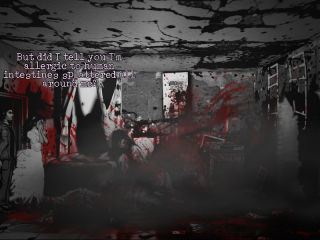

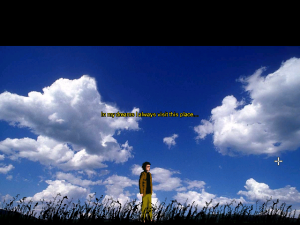

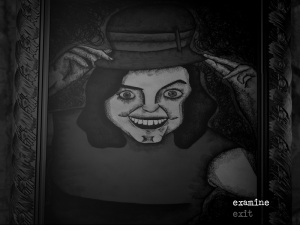

The graphics are gorgeous, mostly black-and-white with splashes of Dario Argento color. Animations are limited, yet polished enough to be acceptable. Some 3D effects are incorporated into the game as well with varying degrees of necessity and success. They are too inconsistently placed. A transition scene when Joe climbs down into the basement, for instance, is the only 3D transition in the game. It isn’t bad, but it really wasn’t needed. The introduction FMV, which guides the player through the increasingly demented rooms of Quiet Haven Hotel, is decent, but much better suited to a trailer than placed in-game. The paintings which coat the walls of the hotel, drawn by artist Victim of Reality, are meanwhile delightfully eerie additions to the hotel’s already-horrific confines.

The new music is fantastic. micAmic’s bizarre, metal soundtrack suits the atmosphere perfectly. Other artists such as Warmer, 5iah, Myuu, Ben and Alfie, and Black Casino and The Ghost are featured to add extra grit and angst to the background. The voice-acting is, unfortunately, terrible. No other way to put it quite frankly?the lines just aren’t read with much certainty, as if the actors aren’t entirely sure what context they are meant to be spoken in. It isn’t game-breakingly bad?and one can skip through dialogue easily enough?but it detracts from the experience, makes certain scenes laughable when they are supposed to be crushing or deep.

Altogether the Downfall remake is something of a more masculine iteration of The Cat Lady formula. Where The Cat Lady gets ruminative and sentimental, Downfall has you tricking a man into setting off a match in a room slowly filling with gas. Where The Cat Lady‘s aggression is manifested through revenge and justice, in Downfall it is almost purely through grit and anger. This path may lead Downfall into excess, but it still seems to serve some purpose, juvenile though it may seem at times.

The Downfall remake is absolutely the definitive version of the game. The 2009 version is included with the remake for the curious player, in case they want the chance to see how Remigiusz Michalski’s development philosophy has changed since his first work.