The attachment formed between a player and a character in a narrative-driven video game is in some ways greater than those formed in movies or written stories. This is due to a higher level of interactivity. Since the player controls the character, they follow the narrative in a more intimate way than a spectator-centric medium. Rarely however is the player-character attachment fully taken advantage of. A narrative-driven video game can and arguably should be a chance to develop a greater sense of empathy within the player.

Themes commonly touched on in novels and movies such as coping with solitude, working through the throes of depression, and dealing with the cruelty of the world would benefit greatly from the potential empathy that can be established video games. They are, sadly, often neglected for more epic topics of world-saving, conspiracy-cracking, crime solving (or creating), and prophecy-fulfilling. There is, to put it differently, a lack of more introspective conflict in video games. But independent games are slowly filling this lack of pertinent real-life themes. Minimalist games like Brandon Abley’s Ex Amante come to mind.

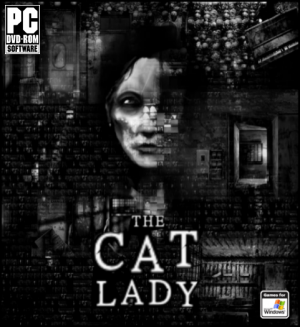

One game, though, makes a markedly admirable attempt to utilize the video game medium to tell an affecting and dark tale of depression, solitude, mortality, and horror. While far from perfect, Harvester Games’ sophomore effort The Cat Lady displays the potential for video games as a narrative medium that meets and potentially exceed novels and movies in terms of emotional involvement.

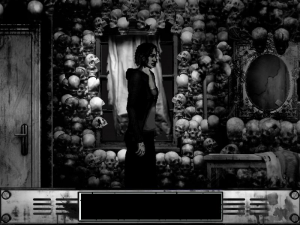

The Cat Lady is a sad game. It begins with a suicide. Not just anybody’s though, the main character’s suicide. Your suicide. No, it’s not even a flash-forward. The first thing you see in this game is the main character actually killing herself. You awaken in a beautiful field and, after some wandering, find an old woman who describes herself as the Queen of Maggots. The Queen tells you that it is not yet your time to die. What’s more, there are five deranged people (or creatures disguised as people) out there known as the Parasites, whose only wish is to cause pain. The Queen will not allow you to die. She grants you immortality and gives you a mission: Exterminate these parasites before they cause anyone else more harm.

And who are you, anyway? Kill five psychopaths. This might be easy for an ordinary action hero type. But again atypically for a video games, the protagonist is a lonely forty-year-old woman named Susan Ashworth. She’s the lady in the neighborhood who nobody pays much attention to because she keeps to herself. She occasionally plays the piano, which lures the stray cats in the area to her apartment. She has no friends, no family, no hope for the future, and only wants the peace death brings. But after her run in with the Queen of Maggots, she cannot have this peace. Susan may be stabbed, choked, and even have her face doused with bleach, but her subsequent deaths are far from permanent. She will wake up healthy in a matter of little time, ready to again challenge the evils infesting her world.

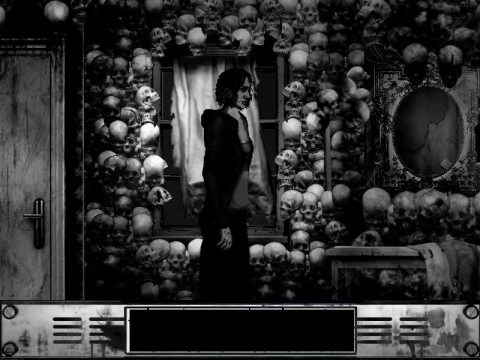

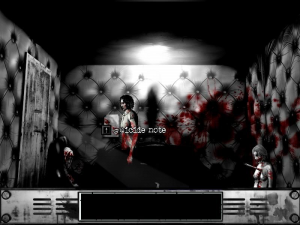

The Cat Lady is a horror game too, and it does not forget this. As with Harvester Games’ first effort, Downfall, it is an unforgivingly explicit experience. Lots of blood, lots of violence, lots of disturbing imagery. Maggots, guts, rotting carcasses. It is in some ways more tasteful than Downfall though, whose constant barrage of horrific phenomena becomes almost comical after a certain point. It is also less sexual, the terrifying things being more of a metaphor for or manifestation of Susan’s depression than a metaphor for the protagonist’s psyche. The Cat Lady manages to keep its horror contained, allowing the player some breathing room and for the contrast between the normal and the horrible to be that much more unsettling.

Gameplay is simple. It doesn’t even make use of the mouse. Action is two-dimensional, seen from a horizontal perspective normally reserved for platformers. With the left and right directional keys you may move Susan across the screen and with the up and down directional keys you may interact with objects. A minimalist approach that does its job. The puzzles aren’t much to speak of, mostly just going from here to there, using this on that, killing the occasional Parasite.

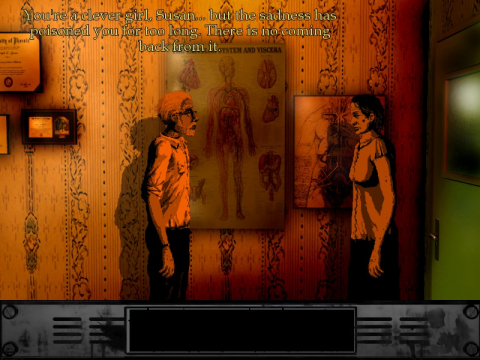

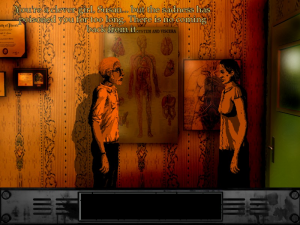

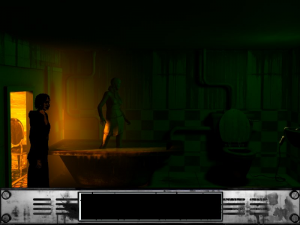

The graphics are a unique and heavily stylized. At an 800×600 resolution, the game is largely monochrome with touches of color on emphasized objects or panoramas. Blood is always colored. There are occasionally gorgeous shots of a black-and-white world against a blue sky or orange sunset.

Susan and the various characters she meets throughout the game move somewhat jaggedly, but it’s still an improvement over Downfall. The close-up perspective isn’t seen too often in games either, so innovation points are due there. The Cat Lady doesn’t quite make use of the opportunities it opens up though. Being so close up, one would expect more elaborate facial expressions and more kinetic action. Nevertheless it’s still a beautiful game. Not graceful, not very active, but beautiful.

The soundtrack is excellent. Like Downfall it is composed by Michalski’s brother Michal, aka micAmic. A few tracks are done by other musicians to mix things up a big. micAmic’s work is an interesting blend of electronic music, porn groove, and a more typical thriller-movie orchestral sound, as per usual. Its uniqueness adds nicely to The Cat Lady‘s overall mood.

For an independent game, the voice acting is excellent as well. Susan’s voice actress in particular, Lynsey Frost, is very good. Some stilted lines here and there, but it otherwise exceeds the expectations one would typically have of a project of this sort.

The plot is… incoherent, to say the least. Indeed the creator, Remigiusz Michalski, has explained in interviews that he did not set out on this project with a completed picture in mind. He let the game grow organically. A story like this is very much divisive. Some reasonably criticize it as a sloppy technique, an excuse to not think too hard but still come off as deep. Others though try to look through a different lens, understand it on a level beyond real and unreal. Two examples come to mind. We can look to the works of David Lynch and H.P. Lovecraft. Isabella Rossellini, Lynch’s former paramour and leading lady in Blue Velvet, explains:

“Most people have strange thoughts, but they rationalize them. David doesn’t translate his images logically, so they remain raw, emotional. Whenever I ask him where his ideas come from, he says it’s like fishing. He never knows what he’s going to catch.”

As for Lovecraft, in his short story “The Tomb” the narrator Jervas Dudley makes a similar point regarding the arbitrary nature of rationality and logic.

“It is an unfortunate fact that the bulk of humanity is too limited in its mental vision to weigh with patience and intelligence those isolated phenomena, seen and felt only by a psychologically sensitive few, which lie outside its common experience. Men of broader intellect know that there is no sharp distinction betwixt the real and the unreal; that all things appear as they do only by virtue of the delicate individual physical and mental media through which we are made conscious of them; but the prosaic materialism of the majority condemns as madness the flashes of super-sight which penetrate the common veil of obvious empiricism.”

So it goes with The Cat Lady. The plot is not rationalized. The supernatural is not explained. What is real and not real within the game’s context is rendered irrelevant. It is then a somewhat disjointed, unevenly paced experience. It adds up in terms of having a beginning, middle, and end, yes, but Michalski makes no great strides in tying up loose threads, explaining the story’s murkier aspects. The effect is dreamlike, with ideas and scenarios flowing in and out, an argument for how thin the veil between reality and fantasy is.

One further justification for this approach is that Michalski created this game by himself in the same way he made Downfall. That is, in the downtime on his job as an auxiliary nurse or during his free time at home. A game created during these little pockets of time seems naturally prone to come out a bit piecemeal.

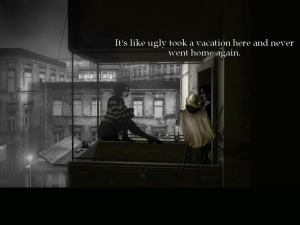

But, again, The Cat Lady is a game designed to make the player feel, not to unravel a mystery. It is a process of experiencing emotions first, a narrative second. Michalski developed Susan as a person to get to know, to get to understand better. He wants us to feel how depression changes a person, to understand why it’s necessary to explore.

As Michalski states in an interview with Alternative Magazine Online:

“I’m not some dark, depressive individual myself, but I’ve come across these issues more often than I would’ve liked to […] Enough to understand the meaning and amplitude of what depression is and how it affects people. And seeing the reaction to these themes through forums and comments from players only confirmed what I feared – it’s pretty much everywhere. And it needed to be said – that even when some try to put labels on this kind of mental suffering and brush it away, there is nothing wrong with feeling that way. But I wanted to show that no matter what cards life deals us, there is always a way out, and it’s not suicide. There is always a reason to go on.”

From this it is understood that the game is about gaining personal strength, carrying on despite burdensome emotions and thoughts, despite loneliness, apathy, and guilt. The obvious comparison is Silent Hill 2, which is centered on characters who similarly experience and cope with intense emotional trauma. And while Silent Hill 2 is a phenomenal example of using the video game as a medium for empathy, and a phenomenal game in general, The Cat Lady builds a more nuanced protagonist, thus creating a deeper empathetic connection.

As interesting as The Cat Lady is though, it’s far from a perfect game. Another parallel with Lynch and Lovecraft: Unique doesn’t mean entertaining. Simply put, it’s not fun. It can be a downright drag at times. The Cat Lady offers little by way of interactivity, only just enough to be engaged in Susan’s plight, but not enough to be truly riveted by the action. This, one conjectures, is brought on by the developer’s lack of technical expertise. The atmosphere and the character development are what move the player forward, not at all the gameplay.

That said it’s more affecting and more lasting of an experience than many other video games. Entertainment isn’t synonymous with fulfillment. This point is understood in the literary and cinematic realms. While the developer should absolutely continue to attempt to appeal to, entertain, and challenge the player, the same tolerance should be accepted with video games.

Links:

Official website

micAmic’s soundcloud

Good Old Games page

Interview with Michalski (one of many!)