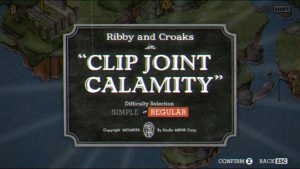

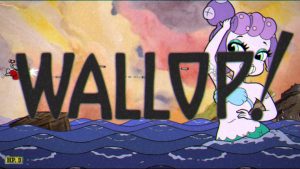

The most easily noticeable thing about Cuphead is that it looks like an old cartoon. Indeed, the game has been heavily inspired by classic animation: early Disney, Looney Tunes, Tom and Jerry – but especially the slightly less recognizable Talkartoons series of cinematic shorts by Fleischer Studios. This isn’t just some passing resemblance or lazy name-dropping: a lot of effort has been put into making every detail of the game look like something straight out of a 1930s animated film (with a notable exception of the whole game being in color as opposed to the mostly black-and-white early cartoons). The watercolor-like backgrounds stand out from sharper but differently colored and more exaggerated moving sprites (which in old cartoons was the result of them being created at different times by different artists), the characters have simple but extremely expressive designs and everyone’s arms and legs act weirdly stretchy, as if there were no bones under the skin. The game is even animated at 30 frames per second, despite the fact that from a gameplay perspective, the game is running at 60 fps. One of the coolest details has to be typography: when choosing the level, a difficulty selection screen will look like a short film’s title card (complete with a fake ‘1930’ release date). The huge text which appears on screen to announce the beginning and the end of a fight is also heavily stylized and uses interwar-style fonts.

The ‘old cartoon’ stylization also extends to the game’s soundtrack. The title screen greets the players with an acapella song describing the game’s premise and from then on it’s mostly non-stop big band and swing-style jazz music, as well as occasional ragtime (not much classical music – aside from that one short but memorable Ride of the Valkyries sample during one of the boss fights – though; once again, Fleischer cartoons and their use of jazz music show up as a bigger influence than Looney Tunes/Merrie Melodies which tended to use classical). There’s almost 3 hours of original music recorded for the game, and it works both as yet another retro reference and as an appropriately fast-paced, chaotic and dissonant background to the title’s gameplay. But while music is on the forefront, the sound effects are no less impressive as many of them were recorded in those delightfully low-tech ways you just wouldn’t expect from (inherently high-tech) video games: they even used the sounds of actual porcelain cups.There’s something brilliant about the sound of breaking glass you hear when your character takes damage.

Cuphead’s Fleischer inspiration goes beyond its presentation though. Cuphead is undeniably an oldschool game and obviously so are Talkartoons – but the interesting thing about them is that they aren’t just oldschool in 2017, they were oldschool from the start. Max Fleischer’s statement criticizing ‘tendencies towards realism’ and embracing what made his medium different from other arts is mirrored by the design of Cuphead with its focus on boss fights, special attacks, hitboxes, pattern memorization and perfectionist play. The game is as unashamedly ‘arcadey’ as Talkartoons were ‘cartoony’. Both see the potential of their respective artforms not in imitation of other media but in developing a style that focuses on their own strengths and makes them distinct from what came before. The cartoons which seem to have served as a direct inspiration for the game – Bimbo’s Initiation and Swing You Sinners – are filled with unexpected transformations, optical illusions, rhythmic animation loops, dark humor, slapstick violence and other impossibilities which simply wouldn’t work anywhere else. Cuphead not only borrows the style of those shorts, it also creates the kind of experience that wouldn’t work without its interactivity, responsiveness and mechanical simplicity combined with difficulty (even if the game isn’t as hard as its reputation might suggest).

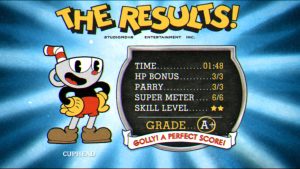

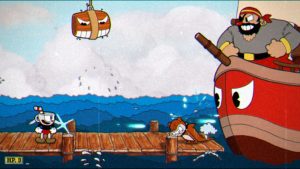

Cuphead is a side-scrolling run-and-gun platformer with occasional horizontal shoot-em-up stages. The player’s moveset is more or less typical for the genre: there’s running and shooting, jumping and dashing, and the additional powerful attacks that need to be charged by attacking the enemies before they can be used. The biggest twist on the formula is the parry slap: if the character is in the air and the player hits a jump button just before colliding with an enemy or a projectile, the object which would otherwise hurt you will be destroyed and you will bounce off it into another jump. Performing parries is essential to scoring high, charges the special attack meter and allows for some impressive combos – so it’s unfortunate that it only works on certain items, highlighted with a bright pink color for visibility. While the game would have probably been to easy if it was possible to parry everything, one can only imagine how far skilled players would be able to go with the combos if the technique worked consistently on all in-game objects. The optional mausoleum levels in which the player has to prevent ghosts, which can only be damaged by parrying, from reaching an urn in the center of the stage just aren’t enough as when it comes to the attack patterns they’re nowhere near as crazy as the rest of the game.

In the shoot-em-up stages, the basic controls are predictable: there’s shooting, four-directional movement, a special attack and the possibility to use parry slap to nullify certain projectiles. There’s also a focus mode activated by holding the dash button, but it is a bit different than the genre standard: it makes your plane smaller and faster, and it reduces the range of your attacks (although the functionality of helping you get out of tight spots in enemy bullet patterns remains). A fully charged special attack temporarily transforms the player’s plane into an angry-looking bomb which can’t shoot anything but explodes on collision and does a huge damage to everything in range. As the game progresses, it’s possible to unlock another weapon: a bomb which travels in a downward arc, which is harder to aim than the straight shot but also more powerful.

The game’s controls are very tight, responsive and intuitive, but with a one large caveat: this only applies to the controller. In general, a fast-paced, precision-focused platformer like Cuphead is not the best game to be played with a keyboard (and this is doubly true for shmup stages where staying in focus mode requires holding down a button, on top of two or three buttons you’ll need to be holding down to keep moving and shooting), but what makes things worse is the atrocious default layout: while the basics of running, jumping and attacking are a sane combination of arrow keys, Z and X, the fact that Shift is used for dashing, Tab changes weapons, holding C allows you to aim without moving and V activates special attacks will lead to your left hand having to contort into some really uncomfortable positions. Fortunately, you can remap the keys.

The game is focused almost entirely on complex, multi-stage boss fights. To go from one world to the next, it is necessary to defeat every boss on a ‘regular’ difficulty (a ‘simple’ difficulty is also available but it doesn’t allow you to progress, so it’s more of a learning exercise). There are also optional platforming stages which reward the player with coins necessary for buying weapons and accessories, plus mausoleum challenges focused on parrying which unlock extremely powerful variations of your special attacks that require a fully charged meter.

The shop is probably the most questionable idea as what it offers is fairly unbalanced: spread shot is one of the first weapons you can get and it’s almost universally useful while most of the other ones are situational, and none of the accessories are nearly as good as shadow bomb which makes you invincible and invisible while dashing: it trivializes some encounters so much that it feels like cheating, it seems almost necessary for the others and there are few situations (for example, near the end of the game) when the fact that it makes you invisible for a while is a serious downside as a precise jump-then-dash-then-parry into an unpredictable position is required to avoid damage. On the other hand, an accessory that increases your health but reduces your firepower doesn’t even feel like an upgrade at all: you may be allowed to make a few more mistakes, but the fight will last longer so you’ll also have more opportunities to make those mistakes.

Cuphead is generally regarded as a difficult game, although it is much more forgiving than it might seem. While the levels are far longer than in something like Super Meat Boy so a failure will offest you by more than a few seconds, you will generally not lose more than about two or three minutes of progress – this is because unlike in old games such as Contra, you don’t have those three lives and a few continues to carry you through the whole game. Your health is just for the current level, it will reset when you leave it and if you fail, you just go back to the overworld.

In general, the game’s difficulty isn’t always fair. It is sometimes possible to get by with just the quick reflexes but many bosses have at least one attack which has to be seen before you’re able to dodge it. Memorizing the enemy attack patterns is also more or less required if you want to get the parry bonuses as the pink objects are often placed in areas you’d rather avoid when playing it safe, staying out of harm’s way as much as possible. There’s also the problem of consistency: some of the levels are noticeably easier or harder than you’d expect given your in-game progress. A few of the fights in the second world (e.g. the dragon) would fit much better in the third, while the third world begins by giving you access to its two hardest boss fights (the bee and the pirate), with most of the things you unlock later paling in comparison when it comes to challenge. The boss rush in the penultimate level is also significantly harder than the game’s final boss: the devil himself. Also, the shmup levels seem easier than all the other ones, although this might come down to how much experience with the genre each player has.

The thing that really stands out about Cuphead’s bosses is how creative they are. Of course, they all work on cartoon logic of free associations and anthropomorphization of absolutely everything – like that moment when the dragon attacks you with fire, which instead of the usual fireballs takes the form of a marching band of indiivudal flames walking on the dragon’s tongue and jumping at you. Even the most obvious references have some sort of a twist to them: it’s easy to predict that when you fight a mouse boss and there’s a cat (looking suspiciously like an early design of Tom from Tom and Jerry) lurking in the background, the mouse will sooner or later get eaten – but it’s absolutely hilarious how after you win the fight, the game reveals that the cat was a robot and the mouse was controlling it all along. And the game is full of those kinds of twists: even during the final challenge, when you’re fighting the devil, he transitions from one stage of the battle to another by ‘undressing’ from his skin and having his skeleton leap into a hole leading to the next area.

Cuphead’s story wouldn’t feel out of place in a 1930s cartoon, but it isn’t saying much as those weren’t really focused on plot. The main characters, Cuphead and Mugman (the latter being only playable in local co-op), lose a game of dice against the devil and the only way they can repay their debt is by collecting soul contracts from other debtors – but they do have a plan to turn the table on their creditor after they gain entry to his lair. There’s not much beyond that (sure, the game technically has two different ending to choose from, but the bad one seems to be more of an easter egg for those who try skipping the final boss) – but it’s not a bad thing as it’s clear that tight gameplay and retro aesthetics are more important here. The story simply fits into the game as a larger whole, like sound effects or menus in other titles.

Like some of the best indie titles, Cuphead is a passion project. It was born out of love for both gaming and those nearly forgotten cartoons. It was developed over many years. All that hard work and effort can be felt while playing it – but it’s also a game that becomes even better after taking a step back to look at just how much the Moldenhauers did to create that authentic cartoony feeling. Cuphead is a game that plays very well, but its strength lies not just in the way it plays. The reason that the game works as well as it does is how well the gameplay ideas correspond to its audiovisual style. The term ‘interactive movie’ usually refers to either the 90s FMV games or modern Telltale-style point and clicks and its not hard to imagine such a game adapting using cartoon-like graphics – but it wouldn’t truly feel as if the gameplay reflected what’s happening on the screen. Cuphead not only looks like a cartoon, it also integrates its interactive elements with its cartoony presentation so well that if those cartoons could be played, it’s hard to imagine that they’d play differently from Cuphead.