Wibarm is the lovechild of Game Arts’ Thexder and Falcom’s Xanadu, two of the most popular games in the mid-1980s Japanese PC scene. Much as in Thexder, you control a transforming robot that can change between mecha and jet forms, as well as using an auto-targeting laser as a primary weapon. But rather than offering a straightforward arcade-like experience, it grafts on some RPG elements, many taken straight from Xanadu.

Taking place in the near post-apocalyptic future, monsters have taken over the Government City’s Power Plant. Far beyond a mere nuisance, these creatures have destabilized its core, potentially causing it to explode and completely destroy Earth. And so Eizel Cloud, member of the super exclusive International Magic Corporation, pilots the Wibarm mecha to exterminate the menace and save human civilization.

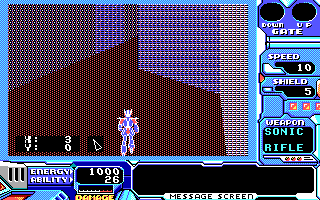

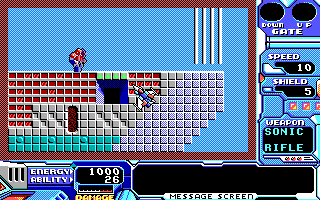

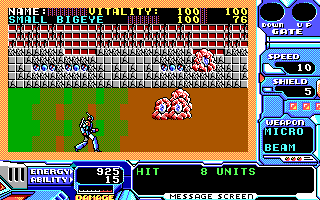

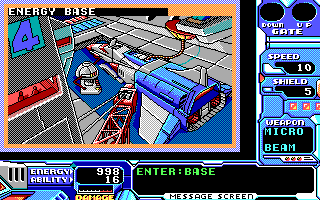

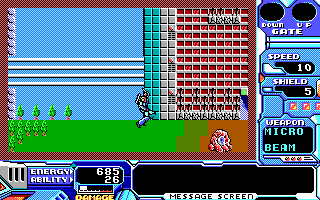

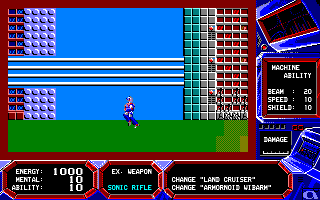

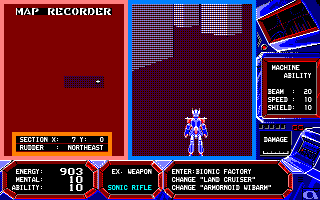

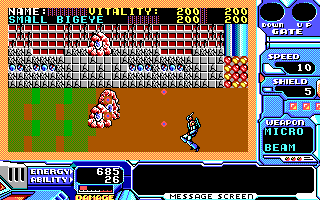

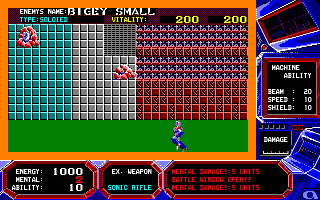

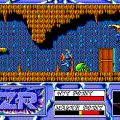

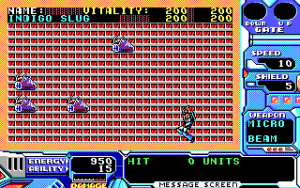

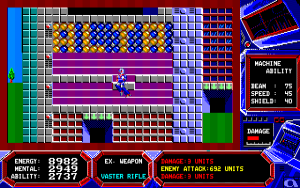

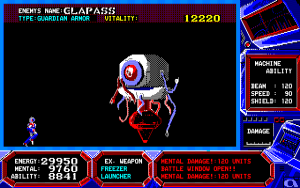

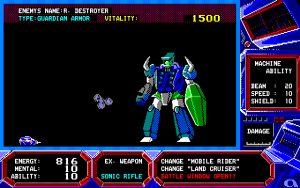

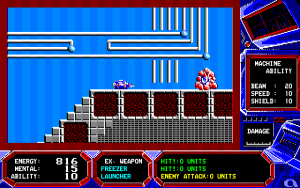

Each stage has a main overworld, a large area that wraps around horizontally. Here, you can change into Mobile Rider form to fly around the stage, drive around in Land Cruiser mode, or walk around on foot in bipedal Armornoid form. Whenever you run into an enemy, it switches to a separate combat screen, much like Xanadu, where you can attempt to dispatch them. Simpler enemies include snails, blobs, one-eyed creatures and small mechas, but more difficult foes look much more imposing, including towering robots and gigantic carnivorous worms. The action feels a little ropey, but certain weapons can automatically target foes or even damage everything on the screen, so it’s usually a matter of hammering the attack button while trying to avoid enemies from hitting you. If you beat all of them, you gain ability points, which is basically just another name for experience points, increasing the strength of your attacks. Your weapon energy is limited, however, requiring trips back to your base to recharge. In addition to energy and repair modules that you can find and use at any time, other items can be found to upgrade your stats.

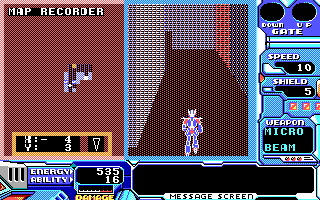

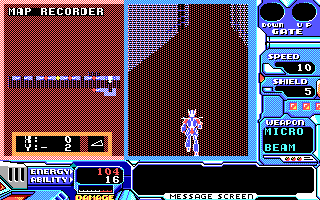

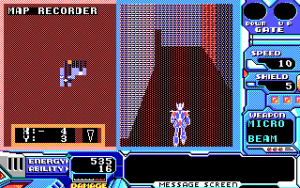

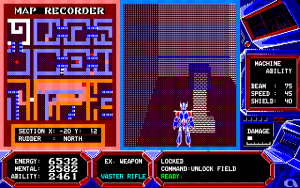

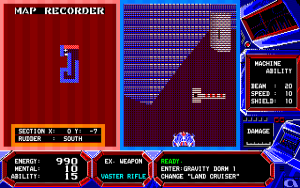

Additionally, spread through the overworld are little doors. Every time you enter one, you’re taken to an indoor 3D dungeon, where you walk around the environment to look for enemies and items. Unlike most first-person dungeon crawlers at the time, which only let you move block by block with static 2D visuals, the dungeons here are rendered with polygons, and you’re able to move around freely, unrestricted by any grid. An automap helpfully tracks your location and important items, though your sensor can be damaged if you’re not careful in combat. Changing into the jet allows you to explore these areas quicker, though it’s also easy to slam into a wall, which sends you back into mecha form. You can also change into the wheeled Land Cruiser, which lets you slip into small areas in the 3D sections, a skill which is otherwise useless in the 2D area. Enemy encounters here appear as static blocks, but again, walk into them and you’ll be teleported to a separate screen to fight them. The ultimate goal in each of the six stages is to fully explore all of these dungeons, upgrading your mecha and looking for the master key that will unlock the gate to the next stage.

However, this is still fundamentally a mid-1980s RPG, one that draws heavily from Xanadu, and that means a whole lot of grinding. You can’t just fight the same enemies over and over, because while defeated foes respawn, their replacements are far more powerful than the ones you killed. In fact, when you first begin in a stage, there are only a few enemies that you’re even capable of damaging at all. There’s no indication of the enemies’ strength until you fight them and see if your weapons are effective, and run away if you’re too weak. Then, you repeat this until you find some baddies you can kill, become slightly stronger, and then repeat the cycle. Enemies in the dungeons are also generally stronger than the ones in the main area, too, so you need to prepare well beforehand.

This is especially important because, when you enter a dungeon, the exit isn’t necessarily in the same spot at the entrance. You may find that your path is blocked by an enemy that’s too strong, in which case, there’s no escape short of dying. And since you only have a single save slot, definitely don’t save your game in the dungeons unless you’re absolutely sure you can leave, because it’s very possible to get caught in an inescapable situation and have to restart the whole game.

This design causes problems right at the outset. You can revisit your base to restore your energy, but curiously they can’t repair you. You start with five repair items, so at least you have something to repair your damage. Stages have repair factories, but these are filled with the same extraordinarily strong monsters at the other dungeons. So if you run out of repair items and can’t find any more before you’re strong enough to defeat the enemies here, then again, there’s no real way to progress and you may as well restart the game.

Dead issues like these, as well as the inherent grindiness, will likely impose a strong barrier to enjoyment for modern game players. But Wibarm’s design nevertheless stands out as a game that not only combined elements of two hugely popular games, but along with its impressive 3D indoor sections, make for an innovative genre melting pot.

Wibarm was the first title from Arsys Software, a company formed by former Technosoft employees who had worked on the original Thunder Force. Among them was Kotori Yoshimura, whose brilliant 3D programming skills had created the impressive racing game Plazma Line, and the dungeon segments in Wibarm undoubtedly exist to show off her technical prowess.

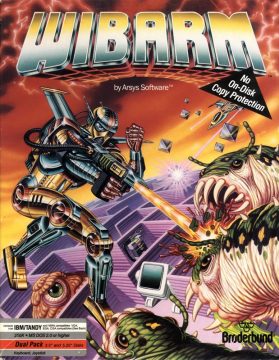

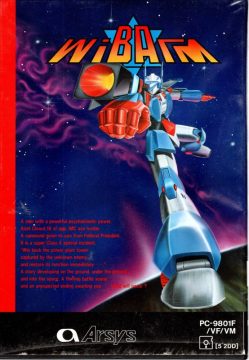

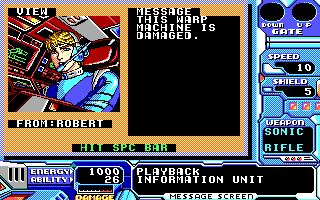

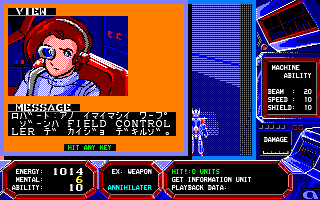

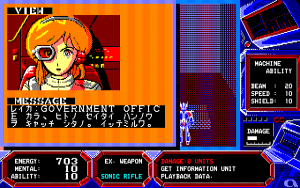

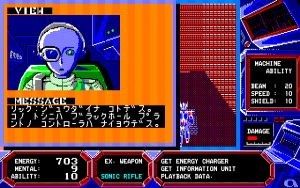

It was also the only title from the company to be released internationally, where it was ported to IBM PC platforms and published in North America by Broderbund. This version has a number of changes, both visually and mechanically. The speed is a little slower, and most of the graphics have been redone, although they look similar. The interface window has been redesigned, and all of the anime-style character portraits have been redrawn in a Western art style. The original Japanese version gives you several weapons at the beginning of the game. You can only hold three at once, so you must return to base in order to switch. This was condensed in the English version, so you only have three main weapons at the outset, so you no longer need to choose. Even in the Japanese version, your weapons have awesome sounding English names like the Megapressure Bazooka and the Hyperflame Projector. However, some are disappointingly weak and therefore redundant.

Additionally, the Japanese version had a Mental stat which dictated your weapons power, with certain creepier enemies dealing mental damage and therefore decreasing your strength. You can use items to restore it, but it also regenerates on its own outside of combat. This was apparently just a little too annoying, so this was scrapped totally. Furthermore, many of the dungeons have been redesigned. The music is totally different in the English version, as it doesn’t support any sound hardware outside of the PC Speaker. Altogether, while it doesn’t play as smoothly, most of the design changes are for the better. However, some technical issues regarding both graphic modes and hard drives make this a huge hassle to play, even in DOSBox, where it requires a specific user disk setup to even begin properly.

This revised version was actually re-released in Japan under the name Wibarm USA. It’s exactly the same as the North American version, still requiring MS-DOS to run. It’s also still in English, though the package included a Japanese language manual. The back text of the box proclaims that, with the new dungeon layouts and balance changes, it may as well be “Wibarm 2”.

Alas, Wibarm failed to capture much of anyone’s attention in North America. It did come a whole three years after its initial release, where its fancy 3D effects were no longer as fancy, among other issues. Arsys’ subsequent game was the extraordinarily ambitious 3D adventure Star Cruiser, which let you explore an entire 3D galaxy in a spaceship, and probably would’ve received more English critical attention had it been localized.

Screenshot Comparisons

Links:

Green Deep Forest – Write-up in Japanese

Additional screenshots from here