Although a competent and interesting 1983 platformer, Pandora’s Palace is one of Konami’s most overlooked games: never ported, never anthologized or referenced in later games, never discussed much except by coin-op enthusiasts. Although best known for introducing Konami’s golden Moai enemies, popularized in 1985 by TwinBee and Gradius, Pandora’s Palace was Japanese-made but only released in North America, which may be unique in the history of gaming. This, plus its dated-looking graphics, suggests a troubled development history that Konami preferred to forget. But it deserves inclusion in the history of coin-op platformers, for balanced and fun gameplay and some original twists on the then-standard Donkey Kong formula.

Like other games including BurgerTime or Mr Do!’s Castle, Pandora’s Palace is best compared to Donkey Kong in gameplay terms. It has that familiar structure: four static-screen levels increasing in difficulty, with platforms and moving enemies, and a cartoonish uniformed hero who jumps and climbs towards a goal before a timer runs out. Simple animated cutscenes fill out the story, introducing the game and concluding each stage. A bunch-of-grapes powerup temporarily lets you destroy enemies by jumping on them. Following even older conventions, points flash up in white letters, and the player has three ‘lives’ with opportunities to earn more.

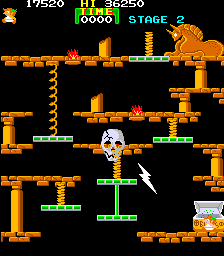

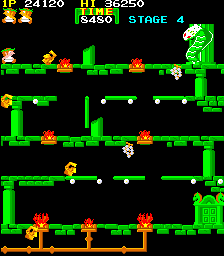

Yet Pandora’s Palace has somewhat distinctive gameplay. You travel downward, not upward: enemies cannot kill directly, but knock you backwards off platforms (falling too far is fatal) or into flames. Platforms dangle, slide, flip, and cycle. The goal is alternately a doorway, or Pandora’s Box itself followed by a bonus points-grabbing ‘Challenging Stage’. In this race to clear the screen of enemies, you stay powered up and won’t die. The timer is a squawking bird approaching the sun. In a humorous touch, time’s up when it hits the sun, shattering it. There are also secrets. In each stage, passing a certain spot triggers a high-value item. Landing accurately (for 1500 points) on three consecutive enemies summons the bird to distribute grapes; hitching a ride powers you up. In stage 1, it can also be triggered to bring another life.

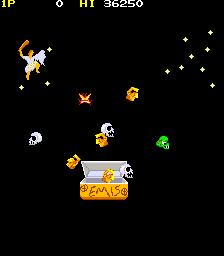

The plot is obscure: evidently the developers had an ambitious story about Greek mythology, but struggled to portray it. Pandora’s Palace lacks any explanatory text in-game. A decal supplied with the kit gave players both plot and instructions in under a hundred words (calling Pandora’s box the ‘Treasure Chest’, stages ‘Chambers’, and the bird a ‘buzzard’.) According to the poet Hesiod (28 centuries ago), Pandora was the first woman, who released every evil from her jar (nowadays routinely called a box); only Hope, ‘Elpis’ in Greek, remained inside. Pandora’s Palace definitely reimagines this myth. The introduction shows a figure suspended above a golden chest, inscribed ‘EMIS’ (clearly meant to say ELPIS) between circled crosses. Stars materialize around him; he shoots one at the chest, releasing the four enemy-types (skulls, golden Moai, green monster-heads, flames). The figure’s club and lionskin, plus the configuration of stars including three on his belt, identify this figure (confusingly) as Orion.

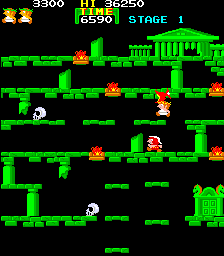

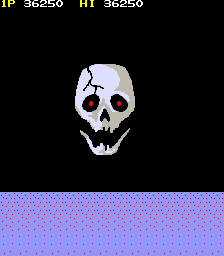

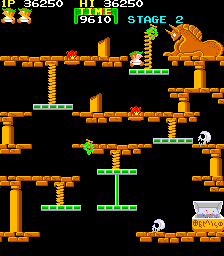

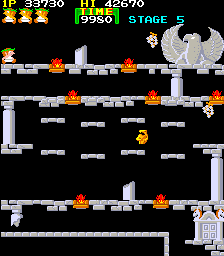

The game then begins with the nameless hero in stage 1: green stonework with a ruined temple in the background. He wears a white toga with laurel wreath, and when powered up, red armor with crested helmet. (Both outfits look Roman, and the stage-designs suggest Egypt and Rome as well as Greece.) Completing the first stage, the hero enters doors and disappears down a hallway. The screen always wipes left, implying progress through endless chambers. The second stage (yellow, with a quadruped monster statue) ends with Pandora’s Box itself. A giant skull—shown laughing ominously in attract mode—arrives mid-screen: the hero hops into the box, pulls out a thunderbolt, and smashes it. The third stage is green with a cobra statue, ending in another doorway. The last is stone-grey with an eagle. This time, when the hero hops into the chest, he blazes with energy and floats to mid-screen.

The game’s visual style recalls Spielberg’s 1981 movie Raiders of the Lost Ark. Ruins, skulls, flames, and cobras evoke its Egyptian scenes. The ancient golden box containing Death recalls the Ark. The ‘golden Moai’ are probably Peruvian idols. But typically for first-generation platformers, the vibe is family-friendly, with cartoony characters and jaunty ragtime music.

Reconstructing the game’s development forty years on is difficult, but clues exist. An announcement in Play Meter magazine shows that it appeared in April 1984. It was a cabinet conversion kit sold by Interlogic (named on the title screen), an Illinois-based distributor which had already marketed two other Konami kits in 1983. In December 1984 Konami bought Interlogic from its founder and CEO, Ben Harel, merging it with their American arm. But why was their finished game neither marketed in Japan, nor ever acknowledged again?

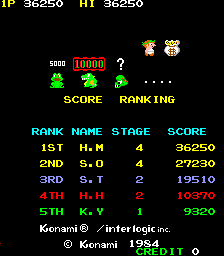

Developers were anonymous in early 1980s games, so they could only conceal their names in the code, or alternatively hide shortened versions in the high-score table. The Pandora’s Palace table contains five sets of initials, with H.M at the top. This probably means that the director or programmer (roles were ill-defined back then) was Hiroyasu Machiguchi. Interviewed in 1999 for Game Hihyou magazine, he recalls joining Konami in 1982 or 1983 aged around 22. He calls Gradius (1985) his first public release, having become development team leader in 1983. Before that, Machiguchi says only that because Konami was shifting from medal games to videogames, many projects were canceled. But 1983 was the year Capcom prepared to publish games in 1984 by poaching at least three Konami staff. The talented Toshio Arima and Tokuro Fujiwara left, plus a certain H. Fujinaka (secretly credited on Fujiwara’s last Konami game and first Capcom game). Perhaps the 1983 industry crash, which began in the console market but also affected arcades, added further pressure. It seems plausible that Machiguchi, an electrical goods salesman who learned about games from scratch, was tasked with completing an unfinished project. Whatever happened, Konami presumably judged the game unsatisfactory and withheld it from the domestic market. Perhaps its Greco-Roman theme was expected to sell better to Americans, or Konami had a contract to honor with Interlogic? Whatever happened, nobody has yet admitted to working on Pandora’s Palace, which speaks volumes.

Another possible symptom of design struggles for Pandora’s Palace is content borrowed from two other games: Fujiwara’s March 1983 hit Roc’N Rope, and Circus Charlie (1984). Konami actually made three four-stage games with golden prizes. First was 1982 maze-combat game Tutankham; second was Roc’N Rope, which introduced Fujiwara’s innovative “wire action” mechanic of climbing with a grappling-hook instead of jumping; third was Pandora’s Palace. The second and third are both Donkey Kong-style platformers, with a goal to reach in four repeating single-screen stages, plus cutscenes. In Roc’N Rope, a pith-helmeted explorer tackles dinosaurs, cavemen, and pterodactyls to reach the ‘Roc’, a golden bird resembling the one in Osamu Tezuka’s famous manga, Phoenix (1954-1988). He collects feathers for points, while powerup eggs make him temporarily invincible. Charmingly, after each play-cycle, the explorer flies away on the Roc’s back. The other influence on Pandora’s Palace (unless the influence went the other direction, or both) is the 1984 minigame compilation Circus Charlie: both feature jaunty music, an extra stage, multiple secrets, and the declaration “1ST BONUS AFTER 20000 PTS”. In the lion-riding minigame, Circus Charlie also involves jumping over pots of fire, and collecting every moneybag summons a bird that brings bonus moneybags.

The secrets in Pandora’s Palace highlight earlier games. The frog “croaks” like Frogger (1981). The moneybag recalls Circus Charlie. The most valuable is a green dinosaur enemy from Roc’N Rope, its four-pixel back plate recolored from red to yellow. But the Roc’N Rope similarities go deeper: the grapes flicker rainbow colors and turn the hero’s outfit red, like the Roc’s eggs. More strikingly, the bird-creature is actually Roc’N Rope’s boulder-carrying pterodactyl, recolored from blue to red. These dinosaurs stand out against the Greco-Roman theme. Konami in-jokes, or Fujiwara’s fingerprints?

At Capcom, Fujiwara developed a Roc’N Rope follow-up that eventually became Top Secret/Bionic Commando (1987). It is unclear whether he left anything unfinished at Konami, but surely a Raiders-inspired platformer, exploring ancient ruins with “wire action” whip-swinging, would be a promising Roc’N Rope sequel. Lesser programmers would have to settle for climbing and jumping.

There’s one last hint that Fujiwara/Arima worked on Pandora’s Palace. After they left Konami, their first platformer was Makaimura/Ghosts and Goblins (Capcom 1985). When King Arthur loses his armor, he is left in his underwear. Perhaps that idea carried forward from Pandora’s Palace, whose hero wears either a toga or armor?

Pandora’s Palace, exclusive to North American coin-op gamers, disappeared without trace. Japanese developers kept reimagining ancient worlds throughout the 1980s, but usually in vertical shooters (in 1986, Capcom’s Legendary Wings and Irem’s Youjyuden; in 1987, Konami’s Battlantis and Hudson Soft’s Hector ’87; in 1989, Namco’s Phelios). Pandora’s Palace the first ever platformer with a Greco-Roman fantasy theme, stands alone. It influenced neither SNK’s Athena nor Nintendo’s Kid Icarus, two more successful examples that appeared in 1986.