When Yume Nikki started to become popular in the West a few years after its initial success with 2ch denizens in 2004, it became obvious that the sometimes-derided RPG Maker tool was not only capable of producing good games, but also very original takes that didn’t even have anything to with RPGs. Indeed, Yume Nikki soon became a cult hit both in its native country and abroad, as well as an icon of what amateur development could do best. Team GrisGris’s 1996 Corpse Party is an earlier example of RPG Maker-made “non-RPG”, but it was somewhat classical in its game design and lacked Yume Nikki‘s distinctive blend of conceptual adventure and psychological horror. However, what a lot of people seems to ignore is that Yume Nikki still isn’t the first in that kind of production.

We need to go way back in time, six years before the Yume Nikki phenomenon. In 1998, the multimedia giant ASCII Entertainment organized its fourth entry in a series of annual competitions where contestants were required to submit a self-made game created using either RPG Maker or developed from scratch. That’s when a man called Nishida Yoshitaka – nicknamed “Yubiningyou” – came in with a strange project developed with the help of RPG Maker ’95 titled Palette. And it didn’t have anything to do with the RPG genre at all.

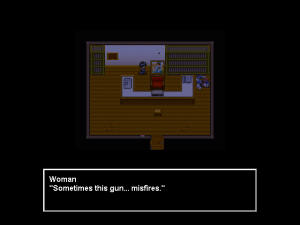

The game starts in the cabinet of Cyanos B. Cyan, a renowned psychiatrist working on a memoir for the Central Newspaper periodical. As it’s starting to get late, he decides to call it a night and go back home. As he’s almost left the place, the phone rings, but when he picks up, there’s nothing on the line but silence, and he concludes it is merely an error. As he walks towards his cabinet’s exit, a female voice suddenly comes from behind the door – an unknown woman is imploring for his help. Puzzled that someone could come and ask for care at such an hour, the doctor declines, but soon realizes he doesn’t have a choice when the woman fires a gunshot through the window. She insists that he helps someone she knows and when he pick up the ringing phone a second time, there actually is someone on the line – a mysterious, languishing girl known only as “B.D.”. She also is apparently amnesiac and blind, as she affirms that the only thing she can remember and can see is the color red.

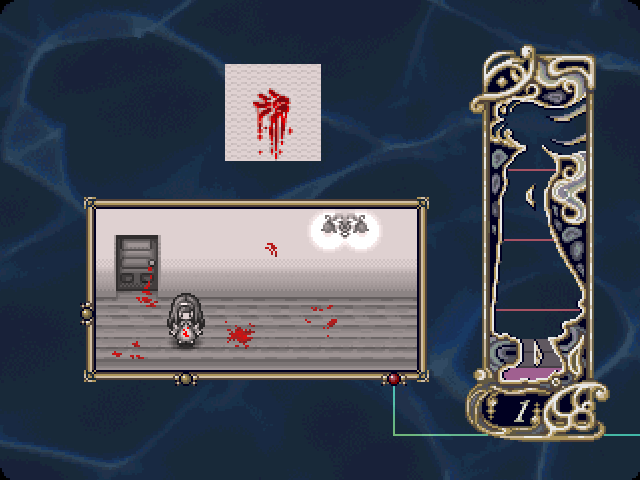

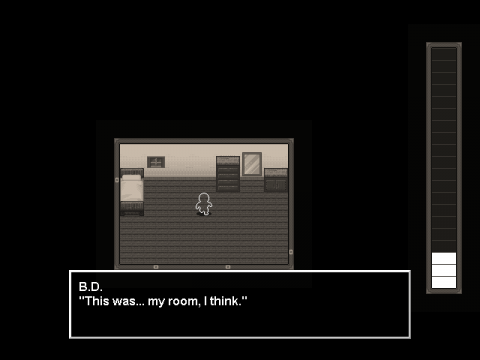

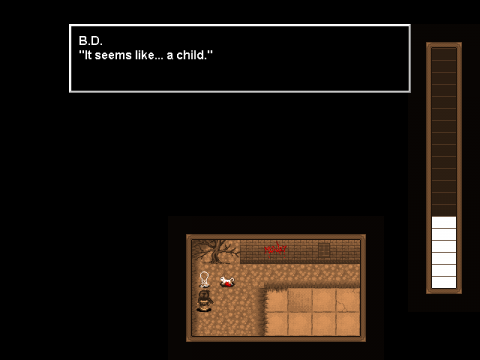

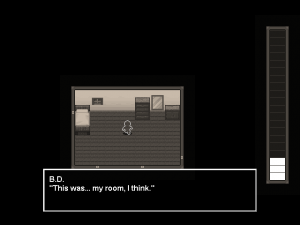

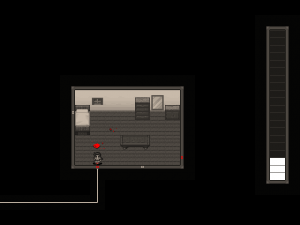

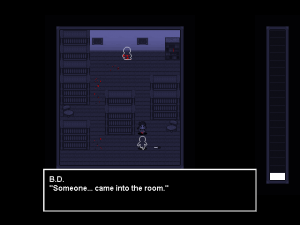

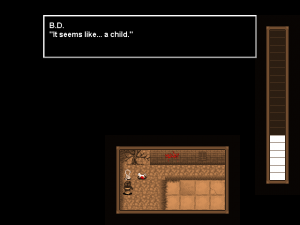

This B.D. is actually the main character you’ll control for most of the game. The girl is completely lost in her own fading memories, a psychic networks of rooms connected through interruptors on the walls and whose halls are obstructed with glass walls. B.D. can wander around this strange mind mansion, but not freely, as; her mental stability is at stake. The gauge representing her recovered memories on the right side of the screen acts as a life indicator, and at every interruptor use or glass shattering, it goes down a notch.

There are also occasional circles appearing on the ground. They’re actually rest areas, where you can replenish your mental stability a bit. However, if that gauge reaches zero, B.D. is struck with a terrible headache and communication is be lost, which sends you back to Cyan’s cabinet. In this case, you need to phone back to regain contact and pursue the introspection. There are thus no “game over” scenarios. The game is based on a relentless and somewhat self-destructive exploration of the young girl’s psyche.

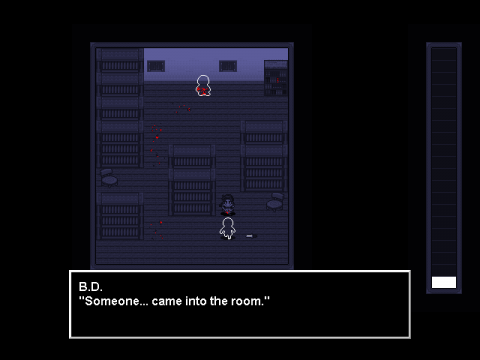

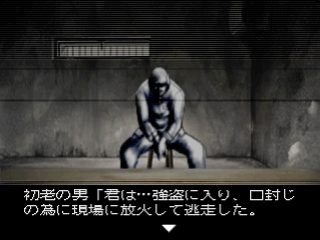

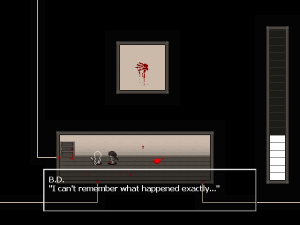

Not all rooms are connected from the start, though, as only interruptors that have turned red are usable. For this to happen, you need B.D. to relive certain moments of her past. When the young girl observes a specific element in a room, she dives back into her memories. Interruptors are then switched off and strange white-outlined figures come out of her unconscious. That’s when B.D. can concentrate on these emerging memories and recall exactly what they mean. Some will reveal themselves easily, like furniture or blood stains, but some other will be reluctant to come back to clarity. This means B.D. hasn’t gained enough memory back to recall what these elements are.

To lift the veil hiding these memories away from B.D., you’ll have to get your hands on “memory shards”. These are tangible fragments of the young girl’s memories scattered around her mind that can be used to reveal the outlines that fit them. For example, the knife shard will be needed to make the weapon appears where it lies. Finding these shards not only means that you’ll get to progress in B.D.’s psyche by provoking her recollections, but also that your gauge will go up one unit, which will allow for more longer and deeper exploration of her mind. When the gauge is at its fullest, it means you are close to uncovering the ending.

The game follows a rather simple progression system: Phoning B.D. from Cyan’s cabinet; wandering around her mind and examine elements to activate interruptors; exploring newly reachable rooms, up until finding a shard; generally, seeing the gauge drop to zero not long after; being set back to Cyan’s cabinet; then starting over again. And it actually works pretty well, especially for such a short but intense game. Nishida managed to successfully create an very conceptual adventure game, blending narrative-led exploration, almost arcade-minded puzzle solving and even die ‘n retry mechanics, where the main motivation for the player is to uncover B.D.’s lost memories together with her.

The interface is rather clear and the game contains no game-breaking situation, which must have been a challenge for an amateur operating very limiting software. Of course, the menu has a bunch of completely useless stats – those are standards implementations in RPG Maker projects – but it never gets in the way and even recalls how original a use of the tool this game is. The only real flaw lies in the rest areas’ weird apparition system, which really isn’t obvious from the start, but you’ll eventually accommodate them.

The game definitely is an amateur work, though. Most of the assets are generic content from RPG Maker ’95 libraries. However, despite this limitation, Nishida managed to create an intriguing atmosphere that backs a thrilling plotline and unusual themes that reveal themselves as we delve deeper into B.D.’s forgotten memories. After the ending, some area remains blurry, but it was left uncertain on purpose so that the player can try to sort out the details of the young girl’s haunting past in his or her own way.

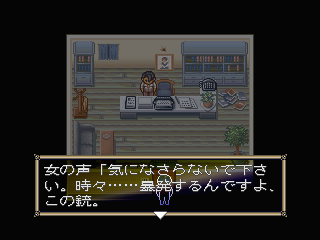

Besides, colors have a great importance in the game’s visuals. Whereas most RPG Maker users were enthusiastic to use a color scheme as wide as that of a Super Famicom game, Nishida created an adventure that’s mostly black and white. Apart from Cyan’s cabinet, only three colors will perturb this monochromia – the sepia and blue-ish tones coloring the exploration sequences, and the occasional patches of bright red that feels like blood stains on old, forgotten photographs. Quite a nice palette choice!

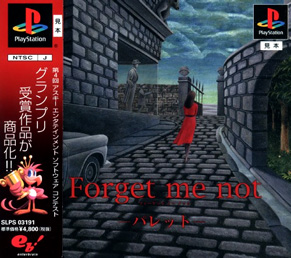

And the game met with critical success with the contest’s jury, so much that he actually came out as the winner of that year’s entry. Nishida won not only a nice money sum of ¥10,000,000 (around $100,000) but also a contract for a commercial retail remake of his game to be released on the PlayStation by Enterbrain.

This enhanced port was released three years later, in 2001, under the title Forget me not -Palette-. And it is indeed a full-fledged remake – original graphics, a CD-quality soundtrack, a perfectly revised interface, and even artwork and voice acting for the cutscenes. From a commercial standpoint, the game wasn’t really a huge hit, especially since it was made available pretty late in the console’s lifespan and was naturally never localized. At least Nishida tasted a bit of how having one’s game actually published on a popular system feels, and that’s great seeing how he basically came from nowhere. Thankfully, the original Windows game ended up being translated by vgperson in late 2012.

So, Palette may not have had the success Yume Nikki would later achieve years later, but not only does it have its own merit as a solid and enjoyable game, but it still can be considered an ahead-of-its-time spiritual predecessor anyway. It’s true the game design isn’t really all that similar. Palette‘s gameplay is subordinate to its final goal, but it definitely has the merits of foreshadowing the eventual popularity of conceptual horror games that make heavy use of cryptic storytelling. The psyche of B.D. is full of striking surprises, and so is the potential output of the RPG Maker software.