In February of 1987, the movie Marusa no Onna (in English, A Taxing Woman), directed by Juzo Itami, was released in Japan. The movie portrays a National Tax Agency bureaucrat and her investigations into businesses doing tax evasion. With its great direction and satirical humor, it became a hit in Japan. It reached number four in distribution revenues among Japanese films for that year and dominated the 1987’s Japan Academy Film Prize, winning six out of seven of its major awards, including Best Work, Best Director, and Best Screenplay.

Capcom released Marusa no Onna in September 1989, being the company’s second game adaptation of a movie for the Famicom (the first was Willow, that same year). The film’s director, Juzo Itami, worked as a producer for the game. Kiyoshi Kurosawa, director known for his contributions to the Japanese horror movie scene, was also credited with helping with the project. Capcom regular Tokuro Fujiwara was the director. The three of them also worked together on the RPG Sweet Home, which was released just three months after Marusa no Onna. One of Sweet Home’s screenwriters, credited as PROBIT, also served as the sole screenwriter for Marusa no Onna’s game. Although Marusa no Onna remained largely forgotten throughout the years, Sweet Home went on to be recognized as a precursor of the survival horror genre and served as the main inspiration for Resident Evil.

One of the first things you notice when playing the game is that it’s certainly not made for little kids. While it doesn’t display nudity and sex scenes like the movie, it features many “adult things”: gambling, mistresses, love hotels, tax evasionetc.It also presents us with many difficult, somewhat technical words related to banking and accounting: record books, passbooks, salaries books, credit unions etc. Looking around the internet about the title, you find many accounts of Japanese people who recollected playing it in their childhood even though they didn’t understand exactly what was going on.

You play as the movie’s protagonist Ryoko Itakura as she investigates businesses to catch tax evaders. The game starts when your boss asks you to go to a pachinko parlor for a tax investigation. While at the the place’s office, Ryoko notices with her attentive eyes that the owner has a Toyo Bank matchbox and tissues, and suspects that is not the only bank he has an account in. After collecting his account book, the team notices the number of transactions is too low for that to be his main account. Ryoko visits banks and goes through their records only to find the owner has been keeping money in secret accounts under his wife’s and son’s names. Confronted with their findings, the owner reveals he had received a book: The Tax Avoidance Manual. “This isn’t tax avoidance, this is tax evasion”, Kyoko says. The book seems to be circulating widely, and the Bureau must investigate this further.

If this sounds a bit boring, it’s because it probably is. Usually, adventure games have you investigating brutal murder cases or solving mysteries in spectacular futuristic worlds. It’s not quite the case with Marusa no Onna.

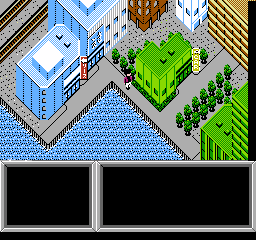

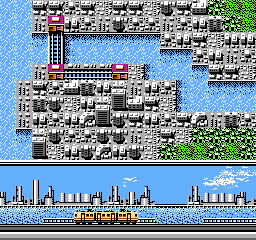

The gameplay consists of visiting businesses and people of interest in search of evidence. After receiving orders from the boss, you leave the office and walk through the map to your destination, which will also require will to take the train. New train stations are unlocked through progression, and each location is based off Tokyo districts.Every time you take the train an animation is displayed, and they differ according to your destination. So, if you take the train to a different island, for instance, you will be seeing an animation of the train crossing a bridge. These are some interesting details for a game of that time, and it adds to the immersion.

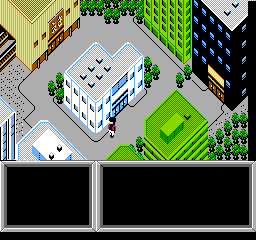

Once you are in a district you need to go wherever it is required to progress into the game, whether it’s a casino, a bank or even a love hotel, but you are free to roam the streets. While there is not much to be explored, you can’t help but appreciate how good and unique the game looks. Few adventure games on the NES had you moving your character throughout the map, especially with isometric graphics, and even fewer of them looked as good as Marusa no Onna. While the map is empty with people, in certain parts of the game pedestrians will appear, and they can be interacted with. These will sometimes give useful information on characters’ whereabouts or directions to certain locations.

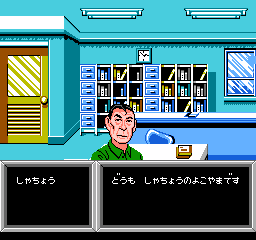

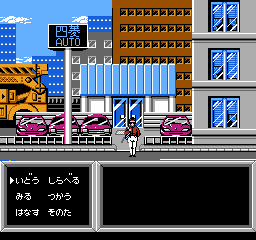

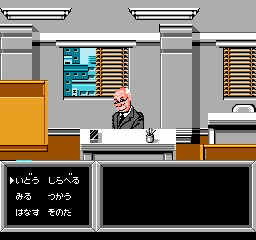

When choosing a location to enter, you’re met with a screen of Ryoko in front of it, which gives more impressive visual details of the building. Once you choose to move into it, you need to speak with characters inside to get the information you need or find physical evidence. There’s not much innovation here when compared to other adventure games of that era. You have at your disposal options such as move, speak, search, look, use etc.

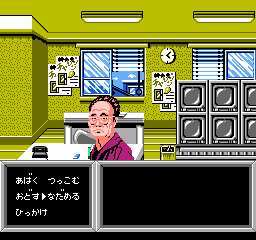

After you gather enough evidence, it’s time to confront suspects with your findings. During these interrogations, you’re given new options: disclose, press, calm, threaten and trick. These need to be selected in a particular order. If you scare the suspect too quickly, they will kick you out of the property, and you’ll have to re-enter the building and start over.

The game doesn’t really require much critical thinking from players most of the time, as Kyoko and her colleagues connect the dots and reach conclusions quite easily by themselves. A couple of times, however, they will have to bring their brains to work to solve riddles like turning a phrase into numbers to discover a password, which will also require some Japanese language skills.

While it may feel more enjoyable watching the movie than playing the game, it could be an appealing title back in 1989 because of its stunning visuals and some interesting mechanics. What made the movie entertaining isn’t its technicalities about tax compliance, but its satirical humor, over-the-top characters, and the relationships between them, and I feel these things have been left out of the game. For example, one of the most iconic scenes of the movie, the first conversation between protagonist Ryoko and antagonist Hideki Gondo, turned into a simple, brief conversation exclusively related to the investigation. Of course, to faithfully reproduce all aspects of the movie into the game would be a hard thing to do considering the limitations of that time.