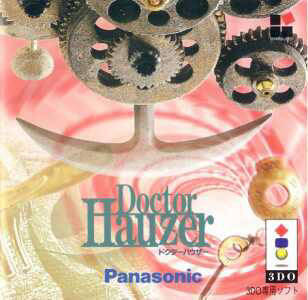

If you’ve heard the name Riverhillsoft, it’s most likely in the context of Overblood, one of the most ridiculous and widely mocked horror games of the classical era. That’s understandable, as Overblood is a bonkers experience that sticks in your brain like few things do (PIPOOOOOOOOOOO!!!). That isn’t all they’ve done, though. Before Overblood, there was Doctor Hauzer, a much worse game that’s more forgivable for its sins because it came out in 1994 and tried a lot of things nobody else was doing at the time – arguably for good reason. It is a fascinating piece of history all the same, if just due to what system it released on and for what region.

Directed by Kenichiro Hayashi (Overblood) and programmed by the eventual director of Dragon Quest VIII (not to mention one of the main creators of Professor Layton), Doctor Hauzer is a 3DO Japan exclusive. Trip Hawkins’ overpriced but ambitious attempt at a more developer friendly console having a Japan exclusive horror game is already weird enough, but that game also using fully 3D models for the environment and including early cel-shading graphical techniques kind of puts it over the weird barrier into historically significant. Oh, and the fact the creator of Silent Hill cites it as a major inspiration for his interest in horror games probably helps.

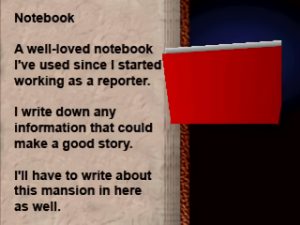

If you’re expecting an overlooked classic, though, you’re in for disappointment. Set in the early 1950s, you play as the young reporter Adams Adler, and you have come to the mansion of famed archaeologist Doctor Hauzer. The good doctor has one missing, and you aim to find out why and see just what his last major discovery was. Needless to say, evil is afoot, and you find yourself trapped in a mansion that seems hell bent on killing you, left over messages quickly making it clear all of this isn’t going to end well.

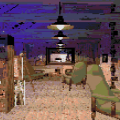

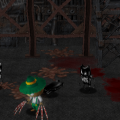

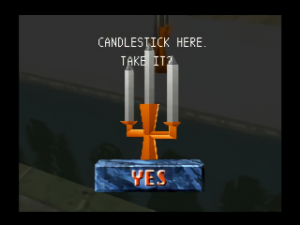

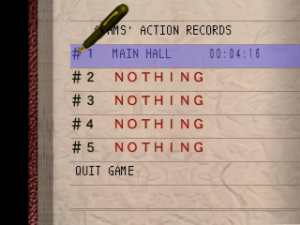

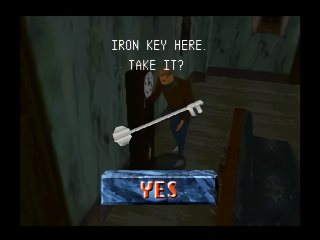

This is less Resident Evil and Alone in the Dark and more a horror themed 3D adventure game that has a spooky end zone where something can actually hurt you like a video game enemy. The rest of the game is item collection, light puzzle solving, very basic platforming puzzles, note reading, and instant death traps, which is a problem due to how long it takes to do simple tasks (save often). The game is a fully 3D experience at a time where anything outside the arcade didn’t really know how to do that with any fitness, and Doctor Hauzer is absolutely no exception. While it’s nice you can switch between three camera angles (fixed third person shots, over head, and first person, the last one actually moving with Adams’ head, including during idle animation), this is a necessity to make the game function around the astronomically low frame rate.

The reason other early horror games used still images for backgrounds was it saved on used space and helped performance with the 3D character models. Doctor Hauzer has so many 3D models on screen at once that it makes the entire game constantly chug at slow speeds, making the old school tank controls genuinely frustrating at point. If you’ve ever heard a hyperbole filled description of why Resident Evil tank controls are bad, know that Doctor Hauzer actually fits that description. It is manageable since the team realized they couldn’t do combat like this and chose against including that, but it does feel like a genuine chore.

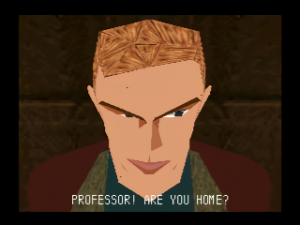

Credit due to the game’s look, though. The cel-shaded style you’re used to isn’t present, but the use of the technique is used here to make some striking models here and there, especially in making Adams expressive in cutscenes. Models stand out properly against the environment when needed, so it’s not a chore trying to see items of interest when laid out on the map. Even with technical limitations, you can see the campy and atmospheric inspirations the team had when making these rooms and set-pieces, the menus having a charming 90s feel that put focus on the 3D models. Even the music is fairly good, matching the mood trying to be portrayed.

It’s not a classic gem, but you can tell it’s not a fully amateur work either. This came out at a time of experimentation, and while this experiment mostly failed, it helped pave the way for more fleshed out and better executed concepts built from its DNA. Even the wacky Overblood clearly took notes from it, like focusing on nailing better performance over trying to create early 3D facial expressions. It’s a bold game with a lot of charm to it, despite its simplicity and sluggishness, enough so that it eventually got an English fan translation. It’s a great example of what this era of 3D gaming was like; confused, strange, and foundational for what would come later, inspiring creators who would go on to make the greats of the medium. If only revisiting it was less frustrating.