- Ultima (Series Introduction)

- Akalabeth

- Ultima I: First Age Of Darkness

- Ultima II: Revenge of the Enchantress

- Ultima III: Exodus

- Ultima IV: Quest Of The Avatar

- Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny

- Ultima VII: The Black Gate

- Ultima VI: The False Prophet

- Ultima VII Part 2: Serpent Isle

- Ultima VIII: Pagan

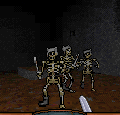

- Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss

- Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds

- Arx Fatalis

- Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire

- Ultima Worlds of Adventure 2: Martian Dreams

- Ultima IX: Ascension

- Lord of Ultima

- Ultima Online

- Ultima: Escape from Mt. Drash

- Ultima: Miscellaneous

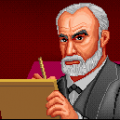

- Richard Garriott (Interview)

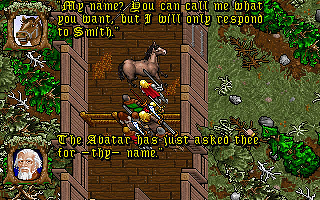

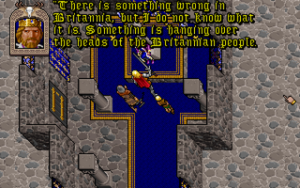

You’ve popped the latest and greatest game from those brilliant minds at Origin Systems into your computer, started it up, and been treated to a lovely title screen. But then your screen cuts out, filling the screen with blue static. Figures, all these game companies expect you to do their bug testing for them nowadays, don’t they? Then a giant red face pops out of your screen at you and and gives you a grin, proudly declaring a new age of enlightenment in Britannia and inviting you to join him. A head-first dive into a Moongate shortly follows.

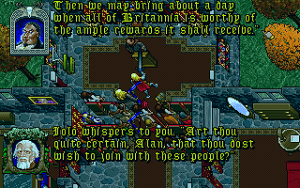

Britannia has moved on without you, Avatar, and 200 years have passed in Lord British’s realm. Life is peaceful and quiet for the most part, until a grisly murder in the town of Trinsic shocks the residents. With no sign of this strange red-faced being in sight, you quickly find yourself caught up in the hunt for clues to this strange, seemingly ritual murder, with old companion Iolo joining you. Though there are no wars being fought, no great ethical quests to solve, and seemingly only mundane problems, this is only a facade. Wizards are inexplicably losing their power, racial tensions between the Britannians and the Gargoyles are at a resounding high, the Moongates aren’t functioning correctly, the population feels spiritually empty for reasons nobody can explain, and study of the virtues seems to have fallen solely into the hands of an organization called the Fellowship, who adopt the poor and disenfranchised that the rest of the realm can’t seem to help. As for the creature calling himself the ‘Guardian’ who seems to be able to speak directly into your mind, he does not seem quite as benevolent as his paternal tone and freely-given advice suggests.

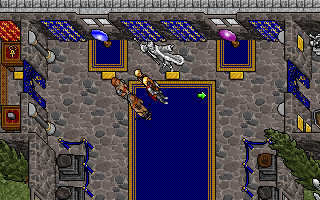

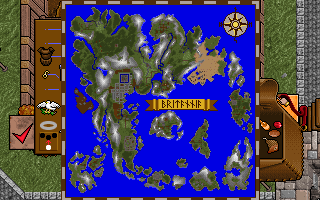

Ultima VII: The Black Gate is widely considered by fans to be the pinnacle of the series. The increasing amount of world detail, game complexity and storytelling maturity that defined every entry in the Ultima series comes to a head here. The game has hundreds of unique characters with their own personalities, lives and personal schedules, an utterly enormous world packed to the brim with secrets, and detail enough to make Britannia seem realer than any CRPG released before (and for the most part, since). Britannia is a single huge interconnected world again like The False Prophet, but scaled up in size. All the familiar old places and locations from Quest of the Avatar onward are here, along with most of the major and minor characters from previous games.

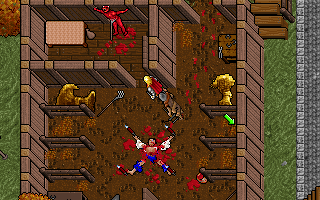

The developers of The Black Gate have packed the world to the brim with details that make Britannia seem real; you can visit the bank to make a deposit (or rob the place – bad Avatar!), take a stroll through the Royal Museum to see artifacts of your past adventures, or visit kitchens and combine water and flour to bake your own bread. Unlike most CRPGs with lots of faceless NPC extras, not only is everyone in Britain unique, but for the most part they have their own houses as well and a rational amount of space for everyone. Towns are gigantic in size and each has its own set of local stories, subplots, gossip and quests. If Ultima VI can take months to complete, Ultima VII can occupy years to pry everything out of the nooks and crannies.

While the label “adult” seems to be essentially a euphemism for “sex” in entertainment, it’s still the best way to describe the depth of the game’s plots and themes. Ultima treads dirt that really no other CRPG has ever successfully covered, even such infamously dark games like The Witcher, Fallout or Planescape: Torment. Divorce, moral absolutism, and drug abuse all come up in game quests, as does the divide between rich and poor, racism, xenophobia, and especially religious institutions. It’s been a long time since the Gargoyle attack on Britannia in the last game, but the two societies didn’t simply mesh into a melting-pot of harmony – like the real world, the cultures tend to isolate themselves despite living in the same land, with tension between them varying. Drug use happens in Britannia (the substance of choice being the fantasy “serpent venom”), showing the deplorable behavior of addicts as well as the dependence it causes. Religion and cults are directly dealt with: a major organization in the game worships a revered founder figure not unlike Scientology’s L. Ron Hubbard or Mormonism’s Joseph Smith, and the game examines practices like specifically targeting the poor or friendless for conversion and the secular power of theological organizations.

Britannia hasn’t been a paradise in the last few centuries, and while Lord British rules as best he can, some people will always just be better off than others. Lord British himself, interestingly enough for a character that began as a straight author stand-in, is shown to have done a few morally questionable things himself, and he isn’t the universally and mindlessly-beloved monarch he was in previous games. A spiritual prophet named Batlin, with Lord British’s permission, has founded a religious organization called the Fellowship which helps Britannia’s people achieve some sense of personal peace and hope for a better future; the group is popular enough to have spread throughout Britannia, especially in the poorer regions. Genre-savvy RPGers used to Japan’s strange obsession with corrupt churches will know already what the organization’s real aim is, but their methods are still impressively presented. What overly-simplistic games like recent morality-heavy RPG Dragon Age do childishly, Ultima VII does with neither a forced moral nor a descent into grimness for grim’s sake.

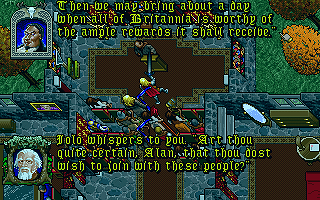

Among the many ways The Black Gate is notable is the inclusion of quite simply one of the greatest villains in the history of entertainment media. The Guardian, who gives this chapter in the Ultima saga his name, is introduced in spectacular fourth-wall-breaking style addressing the player directly at the game’s start, and continues to be the main driving force of the rest of the series. While speech is all but required in high-profile video games nowadays, in 1992 it was unheard of. Laserdisc games like Dragon’s Lair were still confined to arcades, and the multimedia “revolution” of the early ’90s brought on by the CD drive and games like Myst and The 7th Guest was still a year or so away. Actor Bill Johnson’s digitized voice work was an astounding thing to hear at the time (and fortunately, he’s rather better at it than Origin’s staff proved themselves in the FM Towns Ultima VI).

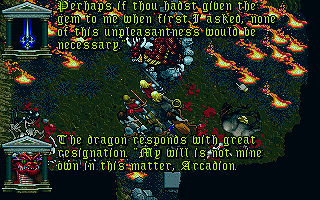

The Guardian plays a major role in The Black Gate from start to finish and interacts with you fairly often, giving advice or comments relating to your actions, or simply being chatty. Though he prevents himself as your friend and provider, there’s something sinister about him from the start, but the full extent of it doesn’t get revealed until well into the game, after his first attempt or two to trick you into murdering or dishonoring yourself. The Guardian is a master of psychological warfare, outright torturing both in-game characters and you the player with taunts, mockery, threats and dangerous advice, sprinkled with just enough truth to keep you guessing about what’s really happening. While capable of brutally powerful magic as seen in later games, the Guardian’s plots go the more subtle route, working behind the scenes, manipulating, and in true super-villain tradition, forcing you to end your quest with a sadistic choice. Richard Garriott has said that while the Age of Enlightenment games were more or less all direct sequels to each other, the Guardian Saga games were the first time he specifically plotted out a multi-game story arc, planning ahead and creating characters that could be carried forward from game to game. Foiling the layers of the Guardian’s plans will take the rest of the series to accomplish.

From a technical perspective, The Black Gate continues to push the limits of computers. At the time when it was released in 1992, for various technical reasons involving exactly how 16-bit processors work, IBM PC machines were actually incapable of giving the game enough memory for it to run. MS DOS could only assign 640k of memory at a time, necessitating the use of a special memory manager written by Origin Systems just for Ultima VII. Understanding exactly how the intricacies of computer memory work is a bit beyond your article author but the practical effect of it is that just playing The Black Gate in 1992 required specially configuring a computer to get it to run, and the advent of 32-bit systems with Windows 95 broke the game entirely. (So for any of you people out there who are into the authenticity of old games on contemporary hardware, please, just use DOSBox on a modern machine for this one). What does it do with all that memory? Digitized speech from the Guardian, a night/day cycle, cloud shadows floating past you, birds chirping in the wilderness, the sound of rushing water from a nearby fountain or the torrential downpour of rain. Similar to Bungie’s masterpiece Marathon 2: Durandal, the designers at Origin chose to use their sound hardware to fill the game with scrupulously detailed environmental effects, and the background music is always unobtrusive and ambient. The end result is highly immersive, and after The Black Gate it’s hard to adjust to playing a CRPG again without birdsong greeting you on sunny mornings.

The keyboard-based controls of previous games in the series are now gone into the mists of the past, and absolutely everything in the game is mouse driven, from movement to interaction, combat and inventory management. With a bit of practice this becomes very fluid and easy, and The Black Gate plays better from a controls standpoint than any game in the series to date. For better or worse, the classic conversation system that has helped to define the series until now is gone as well. No longer are questions asked by specifically typing in a topic during conversations. Instead, The Black Gate uses a branching dialogue tree system like that of the Ultima console ports. On opening conversation, the Avatar has a list of particular topics to select, showing you everything you can ask them about right now. You can only ask about things which your character is currently aware of, however, which closes several potential loopholes and shortcuts like those possible in The False Prophet and earlier games where if you knew what to ask beforehand you could skip ahead.

For example, the game begins in the town of Trinsic where you are expected to do your Avatarly duty and investigate a gruesome ritual murder; leaving town requires a password, which your character does not know and therefore cannot give until he learns it, even if you the player know what it is from a previous playthrough. While this removes some opportunity for sequence-breaking and otherwise manipulating the game, it’s compensated for by the sheer complexity of the rest of the engine. Eight programmers, four artists, four writers, four design assistants, two audio engineers and a production assistant all worked on the game along with Richard Garriott, and over twenty man-years of effort went into creating a ludicrously complicated engine. Ultima VII is paradise for people who hunt easter eggs and secrets in video games, and several features of the Ultima VII engine allow for some fun glitches (see Doug the Eagle’s fansite, linked below), including even more world interactivity than The False Prophet. Near everything in the game can be picked up, prodded, moved around or messed with.

While the Ultima VI game engine gave rise to two additional games in the Worlds of Ultima spinoff series, the Ultima VII engine was only used for one additional game (Serpent Isle). Ultima VII did however popularize a notable piece of middleware called the Miles Sound System. Developed by Origin employee John Miles, who previously was the lead programmer on Ultima V, the Miles Sound System was released in 1991 but developed concurrently with The Black Gate, and has since gone on to become the most successful piece of middleware in the gaming industry, being used in over 5,000 games according to the software’s official website. The Miles Sound System was developed to handle streaming sound and is now part of the RAD Game Tools package. Assuming you’ve ever played video games before, you’ve played something that used this piece of software.

The Black Gate is the first game in the series with several official translations into other languages done by Origin. While previously, fans had translated the games into various European languages and Star Craft and later Pony Canyon had done translations for the Japanese market, Origin themselves translated the game into French, Spanish and German.

The Black Gate is also, notably, the last full game that Origin Systems made as an independent studio. Origin’s games were undeniable, runaway sales successes, particularly the Ultima series and Chris Roberts’ Wing Commander games, but for various reasons the company simply wasn’t making enough money to be profitable. Possibly the biggest factor in Origin’s money troubles was the cost of manufacturing. The CD-ROM wouldn’t come into common use as a storage medium on computers for another year or so when The Black Gate was released, and therefore Origin’s games now, as in the past, came instead on 3.5″ computer disks holding about 1.44 megabytes of data each. While CDs are cheap-to-manufacture stamped sheets of plastic holding a whopping 650 megabytes of data, diskettes were much more expensive at up to seventy cents per disk and holding about 1/450th of that amount each; Origin’s games like Ultima VII and Wing Commander II were large enough to require as many as ten of them.

In addition to the Origin tradition of including extensive feelies and detailed documentation in their packages, the company had by this time grown from a small business to a large studio with multiple independent teams of writers, artists, programmers and designers. With the cost of manufacturing games, publishing games themselves, paying employees and the amount of money taken by distributors at retail, even a sixty dollar price tag per unit wasn’t enough to keep Origin Systems in the black. Origin Systems was also a victim of sheer bad luck, due to a savings-and-loan industry recession in Texas in the early ’90s which caused lending institutions to prefer to “play it safe” by offering loans only to bigger corporations rather than smaller businesses. All of this combined to force the company to sell to a larger publisher if they wanted to stay in business. Shockingly for people paying attention so far, Richard Garriott chose Electronic Arts.

Garriott’s dislike of EA founder Trip Hawkins is legendary for long-time Ultima fans. Potshots at EA begin as early as Ultima II, and Ultima V‘s Apple II version recognized ‘electronic arts’ as a curse word, with NPCs chastising you for using it in conversation. In Ultima VI, players can stumble onto the grave of “Captain Hawkins”, a pirate whose epitaph reads “Here lies Captain Hawkins. He died a hard death and he deserved it”, and whose cruel and destructive deeds form a minor part of the backstory of several quests and NPCs in the game, including other pirates also named after prominent EA employees. Even in Ultima VII, stabs at EA come in the form of major Fellowship leaders Elizabeth and Abraham, three artifacts that must be destroyed in the endgame being shaped like a cube, sphere and pyramid (the components of the old Electronic Arts logo), and the Guardian himself being described as the “Destroyer of Worlds” (Origin Systems’ company motto at the time was “We Create Worlds”).

Fan theory regards The Guardian as an analogue for Trip Hawkins, due to his urge to acquire and then destroy once he gets bored with his toys. That last bit of speculation is probably stretching it (especially since the acquisition-happy EA that gutted Origin, Westwood Studios and Maxis was no longer headed by Hawkins at the time this fan theory began to circulate) but Garriott certainly did not like EA, and only even considered agreeing to sell the company to them after Trip Hawkins had left it to form the ill-fated The 3DO Company in late 1991. Being owned by Electronic Arts had various effects on Origin Systems for the rest of its existence until the closure of the studio and was by all objective accounts a death knell for Origin, but that wouldn’t manifest for some time yet. Ultima fans generally remain extremely bitter towards Electronic Arts to this day for various reasons which will come up later in this article.

In the short term, however, there’s no denying that the infusion of money from EA was just what Origin needed to stay afloat, and for a time EA’s insistence on tight deadlines and developer oversight helped organize and focus the company, among other immediate benefits helping to get Origin’s beleaguered Strike Commanderproject finally out the door. The final Origin Systems release before becoming a subsidiary of Electronic Arts was Forge of Virtue, an expansion pack for Ultima VII published soon before the merger in September 1992. Forge of Virtue added a quest to visit the risen Isle of Fire and the ruins of Castle Exodus. The new quest is fairly lengthy, involving various Tests of Virtue that were designed by the Britannians around the time of Ultima IV but never used due to the Isle’s sinking into the sea, and ends wrapping up various lingering details of Ultima III‘s story, ret-conning the story of Exodus into a new niche in the overall Ultima history. The quest also rewards the Avatar with a powerful weapon called the Black Sword, with a core made out of a demon, no doubt a reference to the soul-blade Stormbringer in Michael Moorcock’s long-running Eternal Champion novel series.

According to the back of the box and to Dragon Magazine, this is the first “expansion pack” or add-in disk released for a computer game, where they define an Expansion Pack as a program which adds additional missions into the main story. (This is different from a “mission pack” or “scenario disk” which adds additional content separate from the main game, which have been in existence at least as early as Nihon Falcom’s Xanadu in 1984). Forge of Virtue had much less development overhead than The Black Gate and allowed the new EA-owned Origin Systems to recoup a bit of their losses on the large-scale Ultima VII and Strike Commander projects, as well as provide needed game patches. Forge of Virtue has long since ceased being available as a standalone expansion and is included in all CD-ROM re-releases of The Black Gate.

Ultima VII: The Black Gate was the last game in the series to receive a console port in English-speaking territories and with the SNES version of Runes of Virtue II, released the same month, the last console Ultima in North America. (Japan received a Super Famicom port of The Savage Empire in 1995 and a PSX Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss in 1997, both published by Electronic Arts Victor). The SNES version of Ultima: The Black Gate is legendary among fans of RPGs, SNES games and Ultima players all for being un-playably awful by anybody’s standard, and attention given to the game in recent years is exclusively of the mocking sort.

If The False Prophet was pushing the capabilities of the Super Nintendo’s antiquated processor and 128kb of memory, The Black Gate shoved them off a cliff. The graphics are chunky, poorly-colored and lower-resolution versions of the DOS VGA original, most of the sound effects that give the game such an atmospheric charm are gone and the musical pieces have been reduced to only a tiny few. There is no customization of the player character, and the Avatar travels alone for the whole game, as Iolo, Shamino and the rest have no option to join you. The world has been shrunken, with far fewer buildings and people, and the NPCs remaining have no schedules and less dialogue. The interactivity of the world that makes messing around in Ultima VII so enjoyably time-consuming is gone, and very few world objects can be messed with now. Limitations of the hardware forced the game to become much more linear with event flags, and many items are inexplicably moved to the dungeons.

Most damningly, though, is the severe damage that Nintendo’s censorship policies resulted in for the game’s story and play. Monsters, for some unexplained reason, explode in a ball of fire rather than leaving bodies behind; presumably suicide-bombers are somehow more family friendly. Rather than ritual murders, you investigate kidnappings. Various words including most notably the word “kill” are gone from the dialogue, as well as nearly everything that could be construed as an adult situation, resulting in a horribly bowdlerized game which demands no thought or moral choice and becomes just another consequence-free, mindless hack-and-slasher of the sort that Richard Garriott has been specifically trying to move away from since Quest of the Avatar. There’s really no reason to play this game at all. Please don’t. It doesn’t even have SNES mouse support.

Ultima VII continues to far and away be the fan favorite of the series and has spawned Exult, a fan-made open source port of the game to modern operating systems and easily the most notable of Ultima fan works. Exult is the best way to play the game aside from DOSBox, and is detailed at the end of this article in a dedicated section on Ultima fan works and fan remakes.

In 2006, Electronic Arts launched a product for the Sony Playstation Portable called Retro Replay, a package of fourteen older Electronic Arts console games including the SNES port of Ultima: The Black Gate. This version appears to be faithful to the SNES original, for what that’s worth. Perhaps as a response, a member of the Exultteam ported the program to the PSP around the same time, allowing PSP owners to play the original version of the game rather than the butchered port.

Links:

Help running the game on an actual MS-DOS machine.

Ultima VII easter eggs, glitches, quirks and other fun.

TheOtherUltimaWiki’s Ultima VII notes.

The Guardian’s introduction in English

The Guardian’s introduction in French

The Guardian’s introduction in German

The Guardian’s introduction, SNES version.

Ultima Retrospective including a good summary of The Black Gate.

Well-researched article in The Escapist magazine by Allen Varney about the sale of Origin Systems to Electronic Arts.

Comparison Screenshots