It’s safe to say the Sega 32X was a failure. Despite a low launch price and early praise from critics, public opinion on the console quickly soured as people flocked to bigger and better systems. Developers working with the 32X must have known this, since the few original games for the system reflect that sentiment. They were the last hurrah of the 16-bit generation, demonstrating what gave that generation its character before the next wave of consoles would wipe the slate clean. Knuckles Chaotix took 2D Sonic games to an absurd extreme, and Kolibri was basically a tropical Ecco the Dolphin.

Far less appreciated is Red Company’s obscure contribution to the 32X: a disco-themed platformer by the name of Tempo. Released in early 1995, the game released just as Bonk was starting to wind down, but before Sakura Taisen saw its debut. So when understood like that, it’s easy to see why the game might have been overlooked: it debuted on a failing system and into a genre that was already heavily saturated. Ironically, though, that’s precisely what makes the game so memorable in the first place. Not only did Tempo show what the 32X could do in the right hands, but it also tried to expand on what mascot platformers were capable of.

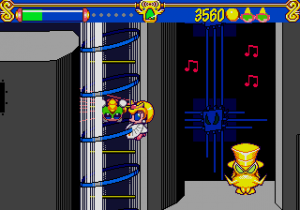

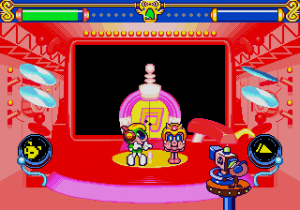

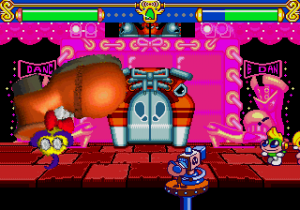

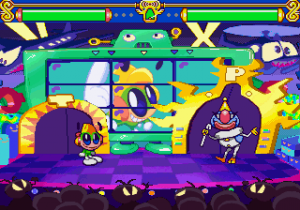

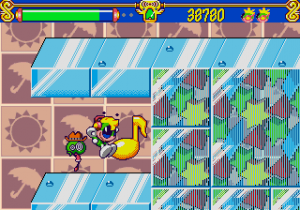

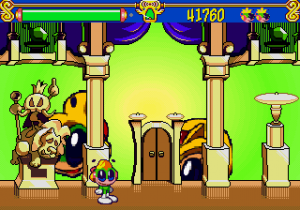

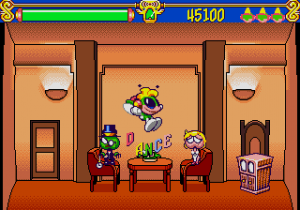

That much is clear by looking at one of the game’s more distinctive features: its art style. At first glance, it looks like many of the game’s artistic choices were made to flex the 32X’s muscle. That’s why Tempo emphasizes its fluid animations, vibrant colors, and pre-rendered 3D bosses: because the technology made them possible. Look a little bit closer, though, and you’ll find the game has a more well realized art style than it initially lets on. Some levels make you feel like you’ve wandered into a music video; they bombard you with flashy pop art and rapidly changing colors, and you pass by enough conveyor belts and monitors to think you’ve stumbled upon a factory-turned-dance-club. (The stylish soundtrack only deepens the feeling.) Other levels are just cartoony, their soft pastels and curvy geometric backdrops resembling cartoons from the 1970s. In any case, the two work well together to create the exuberant dance vibe that Tempo thrives on. Even the bosses’ claymation appearance contributes to the game’s nostalgic overtones.

And we can’t ignore the game’s protagonist, either. His enthusiastic personality helps to set him apart from similar characters at the time. Where other characters were marketed largely for their attitude (think Bubsy and Aero the Acrobat), Tempo’s style is just one part of his personality. He’s also a joyful and expressive guy. Watching him run through the levels, you get the feeling that he’s happy to be here at all. And the animations only reinforce that feeling: Tempo’s loose, rubbery movements lend him both flair and a fun personality.

The only flaw with the game that’s worth addressing is the gameplay, strangely enough. Now this isn’t to say that Tempo is poorly constructed or anything like that. If anything, the game demonstrates a solid understanding of platforming principles. Yet for all its understanding, Tempo is unable to adapt those principles to its own circumstances. The story tracks the eponymous hero’s journey across a dance show called the Major Minor Show, but how much of that is actually reflected in play? Very little, from the looks of it. Gameplay consists of methodically exploring each level for hidden goodies and carefully navigating a sequence of tricky jumps. While such conventions would make sense for a traditional platformer, they lack both the rhythm and the expressive qualities that the disco motifs seem to demand.

Indeed, the game’s dance themes are less a vital part of the experience and more an occasional concession. Or at least they are where the gameplay is concerned. You’ll dance for a few seconds, sure, or maybe you’ll collect a power-up that replaces the music with yodeling, but these are temporary, and they do little to affect the game’s tone. After all, not many of the power-ups you collect actually change how you engage with the levels. They’re tools for tackling challenges, not tools for meaningfully expressing yourself through play. Katy (Tempo’s partner) proves this well enough; she serves the same purpose an option would in Gradius.

The idea here isn’t that pursuing challenge in games is verboten; it’s that it doesn’t make sense for this particular game. Tempo is framed as a dance party, so asking the player to take their time moving through the world just feels out of place and makes the game that little bit less cohesive. Granted, there are moments when the game appears to get it. Some of the game’s most fulfilling moments involve you collecting notes to complete a song, the rhythm-based mini-games, wandering around backstage when the show is wrapping up. Unfortunately, they’re such a small part of the overall experience that it would be misleading to say they represent everything the game does.

At the time, reception for the game was mixed. GamePro praised the game for its beautiful aesthetic, and Famitsu gave it a respectable 30/40. Meanwhile Game Informer condemned the game with a 3/10 score. Although they gave that score in 2003 (well after the 32X’s heyday), it’s not as though those attitudes didn’t exist at the time. Gamepro reviewers still expressed ambivalence, seeing the game as another unoriginal mascot platformer. (The clumsy rap intro probably didn’t help.)