Taito’s Operation Wolf is not the first light gun shooter, but it is one of the most historically important. Throughout most of the genre’s early life, these were digital replications of mechanical shooting gallery games that had been popular for decades. The most famous of these are games like Nintendo’s Duck Hunt and Hogan’s Alley, or Sega’s Safari Hunt – static screens where you had to shoot targets, and then were graded on accuracy.

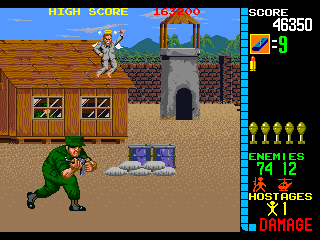

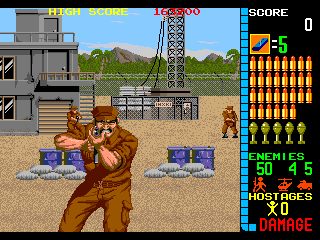

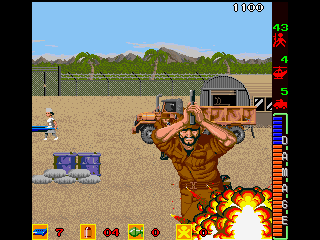

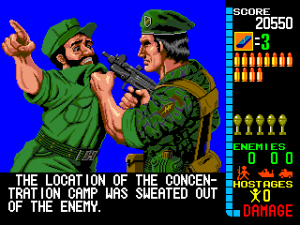

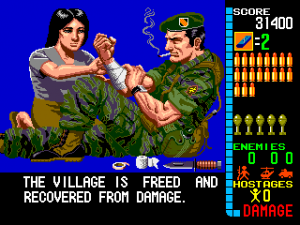

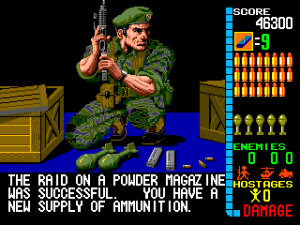

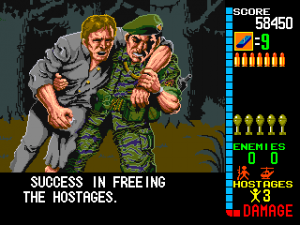

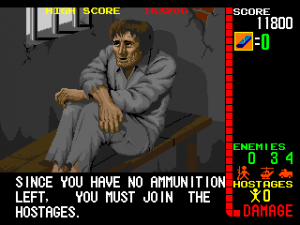

Operation Wolf changed all of that. Instead of playing as a marksman or a hunter, there’s an actual story to frame the action, inspired by American 80s action movies like Rambo: First Blood Part II and Commando. Here, you’re a soldier tasked with gunning down bad guys and rescuing hostages in a South American nation. The action no longer takes place on a single screen, but rather scrolls in one direction, with enemies approaching from several distances and from all sides of the screen. Enemies in the distance appear small, but some will pop up right in front of you, allowing you a look into their eyes before you murder them. Some even pop up from above, as if they were hanging by a rope! The level of detail in these sprites is quite remarkable for 1987. There are also impressively illustrated stills when beating stages or dying.

The targets obviously fight back, and while you have a seemingly generous life bar, it drains very quickly given the constant onslaught. Enemies attack relentlessly, flashing right before they fire so you can make a quick attempt to shoot them first. They’ll also throw projectiles like knives and grenades which you can shoot to deflect and protect yourself from damage. Each level has a quota to kill a certain number of human soldiers, vehicles (cars or boats) and helicopters, and the stage will scroll infinitely until completed. There are also bosses you must defeat before you can complete certain stages, like armored foes that must be shot in the head to kill.

Rather than a pistol or a hunting rifle, you wield an Uzi-style machine gun, allowing for rapid fire. The gun also vibrates when you fire, giving an intense feeling as you pump enemies full of lead. While accuracy is encouraged, you don’t have to perfectly aim every shot, which also gives the action some extra thrill. You also have a limited amount of explosives, activated with the button on the side of the gun, which has a much wider damage radius than bullets and can effectively destroy vehicles. However, they can also damage hostages, so you have to be careful with their usage. In the arcades, Operation Wolf uses a light gun, and light guns will cause a quick white screen flash to determine your shot location. The rapid gun fire means rapid flashing, which can make the action difficult to see, and potentially give headaches (or worse, seizures).

You don’t have unlimited ammo, though, as each ammo clip has 40 bullets, and while you begin each new life with several to spare, you can chew through them very quickly. Ammo clip replenishments regularly appear on the playing field and are collected when shot. If you run out of bullets, they automatically regenerate at a very slow rate, giving you a weak defense that should hopefully keep you going until you find more clips, but you also can’t last too long in this state because you’ll get overwhelmed with enemy fire. There are actually two different game over scenes when you run out of health – if you lose with no ammo then you’ll be captured as a prisoner, but you’ll be killed if you have bullets remaining. (Which is worse for your hero?) You can also find health drinks and grenade replenishments on the field, and are also sometimes revealed by shooting animals like birds. (For those concerned about animal cruelty, these animals are not killed by your bullets, who continue on their way even after dropping items.) Most levels have civilians like nurses, boys in baseball caps, and bikini-clad women that you must avoid shooting. Certain stages also have hostages that you can rescue by shooting their prisons, then must protect them from enemies until they escape. The number of hostages rescued determines what kind of speech the president gives you at the end of the game, potentially offering a handshake for a job well done or chewing you out if you killed all of them.

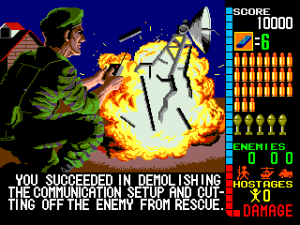

The Japanese version lets you pick from four different stages when you first begin the game, each granting a certain bonus when completed. Beating the communication station will decrease the number of enemies in subsequent levels, completing the village will restore your health, and beating the ammunition depot will replenish your arsenal. The final two stages, the concentration camp and the airport, must then be completed to finish the game. The English version instead enforces a specific level order, removing this level of strategy. Arcade boards can switch their regions via a dip switch, while home ports go by the rules of their region (Japanese versions let you pick stages, American/European versions don’t). In both versions, you may randomly get drawn into additional action scenes in between levels (these types of surprise stages are dubbed “accident” levels in Japanese), which are static screens where you need to kill a certain number of enemies to proceed.

Operation Wolf only has a little bit of music, which is absent during gameplay, but it’s just as well since it would be overwhelmed by the bullet fire and yelling sound effects. There’s quite a bit of digitized speech though, with some of the goofy text spoken in English even in the Japanese version. “You have sustained a lethal injury. Sorry, but you are finished here.”, the game dryly laments when you get killed.

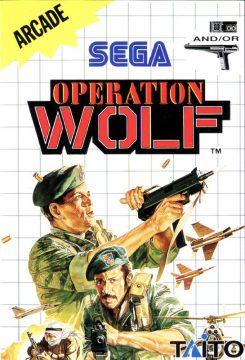

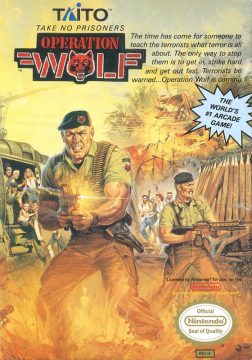

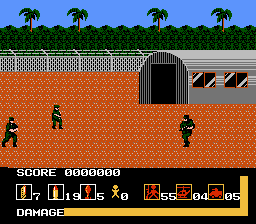

The real appeal of Operation Wolf lies with holding that gun and blasting enemies in an arcade cabinet, but the game was massively popular and so it received several ports. The FC/NES version loses a lot of visual fidelity, and removes the large up-close enemies. This version also removes the bikini lady and renames the “Concentration Camp” stage to “Prison Camp”. The Master System version, released only in Europe, is based on the NES version except it looks a little nicer, but is still missing the large enemies. It’s a little disappointing considering that Sega’s own Rambo III for the Master System, itself an Operation Wolf clone, looks much nicer despite coming out two years earlier. Both 8-bit Operation Wolf ports support the Zapper and Light Phaser, requiring the user of a controller to use the bombs, but can be played solely using the controller as well, with the option to change the cursor speed. Given the type of trigger on the light guns, they don’t quite have the rapid fire feel of the arcade machine gun.

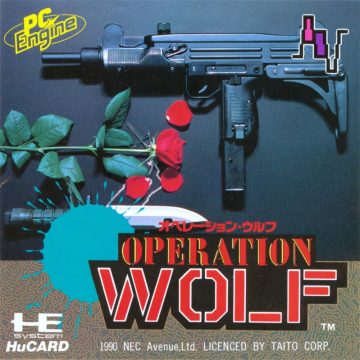

The PC Engine version is the best of the contemporary ports, looking very close to the arcade, though it’s missing the digitized speech. However, since there was never any light gun peripherals, you’re stuck with just the controller. Perhaps to make up for it, you can play with two players simultaneously if you have a multiplayer adapter. This version also lets you adjust your cursor speed, but you need to make this choice on the title screen and can’t change it mid-game. This version also has a curiously poetic cover, featuring a rose next to a machine gun. The console ports also move the status bar from the right side of the screen to the bottom, allowing for a wider gameplay field.

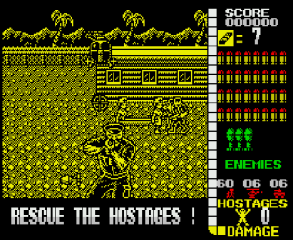

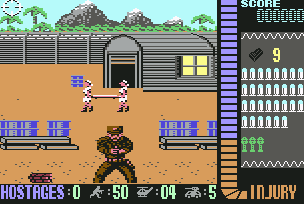

Operation Wolf was also ported to several home computers. and these conversions are generally very good. The ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC version look relatively decent considering their hardware, but they play a little too fast, with both using fairly small screen. The Commodore 64 uses a larger part of the screen and runs about the correct speed, except the crosshair disappears when you fire, making it difficult to track. Certain releases also have support for the Magnum Light Phaser.

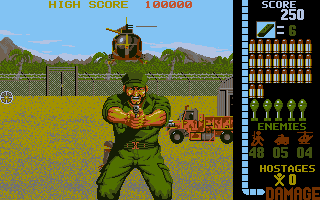

The Atari ST version looks reasonably close to the arcade game outside of the smaller color palette, but the animation is very slow and choppy. Perhaps to compensate for the slower pace, enemies are much more numerous as well. The Amiga version is slightly better, but not as smooth as it could be. The IBM PC version has less colors but runs much smoother; still not as fast or as smooth as the arcade, but a big improvement. Platforms that support the mouse allow you to use them for better aiming, but on platforms that don’t have a light gun, you’re stuck with either a joystick or a keyboard. The Japan-only FM Towns version is close to the arcade version, though it reorients the status bars like the 8-bit console ports to have a wider view, and even includes an in-game CD audio soundtrack not featured in any other release. It also has an unusual loading screen showing a cutesy anime girl in soldier garb.

Operation Wolf also appears in arcade emulated form on the Taito Legends/Memories PlayStation 2 collection, adapted to use the Dualshock 2 controller, and is included on the Arcade Memories Vol. 2 cart for the Egret II Mini. The arcade game is also featured on Operation Night Strikers for Windows and the Switch, featuring Joy-Con motion aiming on the Switch as well as mouse support. Both Japanese and international variations are included, as well as easy variations of both. The NES and SMS ports are included as DLC. Both the Egret II Mini and the PC version of Operation Night Strikers support the Cyberstick accessory, which replicates a positional controller. There’s even a gun-shaped add-on accessory for the Cyberstick, which is about the closest you can get to playing the arcade game at home without buying a cabinet.

In most original releases of the game, the story is pretty basic: an American soldier is sent to rescue hostages in the South American jungle. Operation Wolf’s sequel, Operation Thunderbolt, gives the name Roy Adams to the protagonist. The PC Engine manual gives a slightly more elaborate story: a coup d’état in the fictional South American country of Cherigo has taken over the government and taken hostages of the former government as well as American emissaries and other political prisoners. The player, a Vietnam vet turned mercenary, parachutes alone into the jungle in order to rescue them. This is a wildly ahistorical setting considering the American government was far more well known for orchestrating South American coup d’états instead of fighting against them.

Screenshot Comparisons