Beat-’em-ups should be played with a little aggressivity, a little focused anger. In order to really enjoy what the genre has to offer, you have to approach every enemy like you mean to hurt them. Perhaps that’s why almost every classic of the genre was born in the arcades of the ’80s and ’90s, noisy, vaguely disreputable places where you had to play standing up, constantly on edge as you tried to make the most of your handful of quarters. Then, of course, there is the huge technological gap between arcade boards of the time and home systems; porting over meant cutting many things out, including typically the number of enemies the player would face simultaneously, and much of the intensity would be lost. Thus, decent console originals are not that common in the genre, the most famous exception being the Streets of Rage trilogy.

Much less famous, though still worth a look, is 1992’s Mystical Fighter.

The first 16-bit title developed by the little-known KID Corp, whose output up that point mostly consisted of NES action side-scrollers like Low G Man or Banana Kid, and published in North America by a Dreamworks Steven Spielberg had nothing to do with, Mystical Fighter didn’t seem to attract much notice at the time of its release. What little writing can be found about it online seems to be mostly the result of people stumbling upon it through emulation. This includes this very article, because even as a Sega fanboy and avid beat ’em all fan at the time, I only heard about it almost 10 years later.

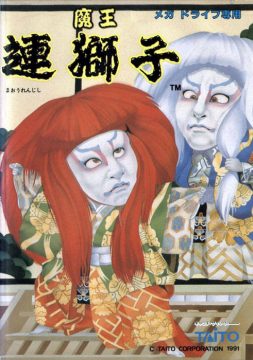

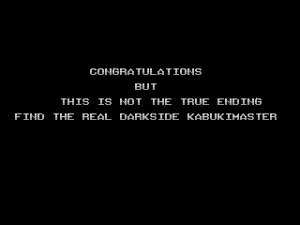

There is no story presented in the game itself, not even the customary text intro. The only non-functional text in the game (we’ll get to it later) refers to the final boss as the DARKSIDE KABUKIMASTER, but that’s all we’re told. Being an action game from the early ’90s, this isn’t a big deal. The manual tells us that about 300 years ago, the legendary White Lion and his palette-swapped second player alter ego Red Lion, otherwise known as the Mystical Fighters (and possibly the LIGHTSIDE KABUKIMASTERS), were summoned to repel the invasion of the Mystical Kingdom by the Evil Kabuki Lord. Just as they had him cornered, they were banished to the Underworld, which is where the game begins.

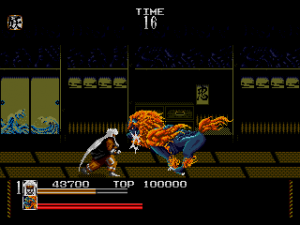

The first thing you’ll notice, then, is the setting. White and Red Lion were apparently inspired by a famous Kabuki play titled Renjishi, which the game’s original title directly refers to. In this mythical Japanese underworld, you will fight sumo wrestlers, undead samurai, kunoichi, yakuza swordsmen and various types of demons inspired by Japanese folklore. The game’s visuals aren’t nearly as inspired as SNK’s Sengoku Denshō; the good news, however, is that it plays better.

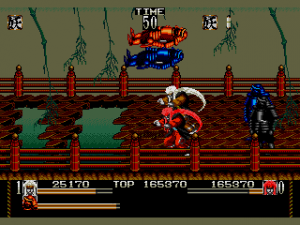

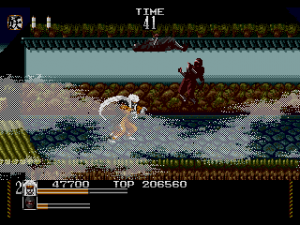

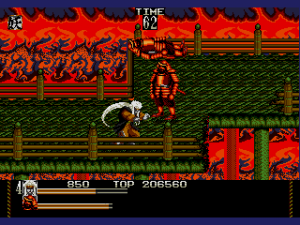

The Lion boys are fast and mobile, able to roll from one end of the screen to the other in a hurry, ending it with a slide kick or jumping attack. Of course you’ve got the regular punch combo and, similar to Golden Axe, you can use magic attacks by picking up a maximum of five scrolls throughout the levels. Those spells aren’t very powerful, and very scarce in “Hard” mode, so they don’t play as large a role in this game as one might expect. Likewise, there are few weapons to be found, of a meager two types: the Jitte, used for stabbing, and the Fan, which works like a boomerang; after throwing it, it’s possible to catch it by timing a punch just right as it comes back towards you. Both magic scrolls and weapons are much more plentiful in the Japanese version, and the spells more powerful, making them more relevant to the overall experience. One of the mainstays of the beat’-em-up moveset, the crowd control attack that costs health to use, does not feature here. This makes the final category of attack the most important: the good old throws. Here at least, there is bit of variety, as the Mystical Fighters can pull off a decent three throws: you can either throw an enemy in either direction, preferably at its friends or in a pit, grab one and spin it around, knocking its partners down before throwing it offscreen, or finally, by grabbing an adversary and pressing jump then attack, pull a suplex that hurts anything it touches. While similar to Mike Haggar’s famous move from Final Fight, the Lions go a step further by actually flipping over along with their opponent, landing head first before rebounding into a jump (which you can turn into a jump kick, a useful combination in some circumstances). This is the coolest move in the game, and the most damaging. Using these is essential to avoid being overwhelmed, particularly in single-player, and they are also a great way to get rid of the smaller, more annoying monsters; you can kill several of them instantly by throwing a larger opponent at them.

It’s a challenging game. In the later stages, one’s playstyle must become almost acrobatic, throwing enemies at each other, jumping over a shuriken, running to hit this one and dodging that one’s sword. Ultimately, playing with the default settings amounts to a practice run; after defeating the Stage 5 boss, you will be greeted with a message that reads:

If you didn’t get the hint, after the credits you’re told to TRY THE NEXT LEVEL. In other words, play it on “Hard”. It can be done with some practice, but it’s no easy feat, even if you set your lives to 5 per continue rather than the default three. While score carries over until you use a continue, the only way to earn extra lives is to accumulate a large amount of score without losing a life, encouraging you to play like every life is your last. It wasn’t always this way; the game was made significantly harder in almost every way for the North American port, so those who find it too much will want to play the Japanese original. Its only downside is that your character’s regular walking speed is slower, which makes is harder to grab enemies and dodge attacks. Finishing the North American version will unlock an absurd “Hardest” mode; while two skilled players with some patience might be able to overcome it, the jumping monsters, known as Gaki, will tear a lone player apart without mercy.

In either version, the stages are decently paced but mostly uneventful. The exceptions are Stage 5, set on a bridge surrounded by hellish flames that flicker red and blue and from which you can throw off nearly every opponent, and Stage 6, the true final stage, a sort of boss run set in a what appears to be a floating Japanese castle’s inner room.

Also of note is that, owing maybe to KID Corp’s experience with other types of side-scrollers, there are pretty well-hidden rooms in which you may find sushi to restore your health, weapons or a bonus stage in which you attempt to catch water drops in order to regain health. The bosses are also more pattern-bound than is usual for the genre, and fighting them properly involves findind and exploiting their weaknesses.

On a technical level, the game is essentially average for 1992. Aside from the first part of Stage 1, an ancient Japanese city at night, and Stages 5 & 6 mentioned above, the backgrounds are rather plain and lacking in details, particularly when inside buildings. Outside, the fact that it takes place a night results in some cool color patterns at least. The sprites are decent but nothing stands out as truly impressive and the magic spells are a mixed bag. The first three aren’t so spectacular, while the snowstorm looks pretty nice and the final spell has you invoke what looks to be a bearded monkey on a cloud to fly back and forth around the area. The soundtrack consists mostly of the sort of fast-paced music common to action games of the era, with sounds evoking Japanese instruments incorporated in a few songs. Some of it is quite good, while one’s appreciation of certain tracks will depend on whether they enjoy some of the Genesis sound chip’s strangest sounds.

Unsurprisingly, given its obscurity, the game never received a sequel, remake or re-release. KID went on to develop a number of ports of Technos games for NEC’s PC Engine and PC Engine CD in the following years. Among those, most of the Mystical Fighter team was responsible for the excellent PC Engine CD version of Double Dragon 2.

In the end, Mystical Fighter isn’t first-tier. It doesn’t provide the visceral satisfaction and intensity of Capcom’s best arcade beat-’em-ups, the methodical brutality of Technos’, the exciting level design and classic soundtracks of the Streets of Rage trilogy, or the variety of weapons, quick pace and mean-natured badassness of Konami’s Vendetta. But it’s a fun, smooth playing game with a seldom-seen setting that should be worth a playthrough for any fan of the genre.

Links:

Sega Retro: Mystical Fighter has scans of the manual, which features some nice illustrations of the moves and characters (the Japanese manual has them in color).

Mystical Fighter Mobygames lists game credits.