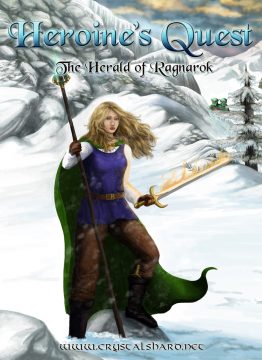

Heroine’s Quest: The Herald of Ragnarok is the very definition of a labor of love. Originally conceived in the mid-2000s as an ode to Sierra’s Quest for Glory franchise, the game was made by the indie development group Crystal Shard and released for free in 2013. It lives up to its Quest for Glory inspiration by offering a similar blend of point and click adventure and RPG skill-building, but goes one step further, arguably surpassing the series that Lori Ann and Corey Cole created with an intricate Nordic setting and deeper roleplaying mechanics.

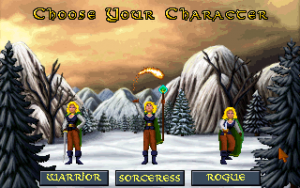

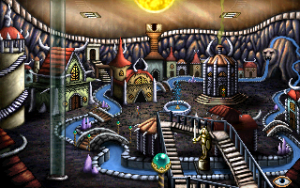

Heroine’s Quest tasks players with choosing between the roles of warrior, sorceress and rogue to save the realm of Jarnvidr from Egther, last of the frost giants who hopes to usher in the twilight of the gods, also known as Ragnarok. Featuring a number of locations and characters straight from the Prose Edda, the 13th century poems that defined Norse myth, Heroine’s Quest feels distinctly rooted in real-world mythology to a degree deeper than any of the Quest for Glory games.

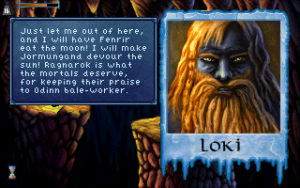

Quest for Glory I, for instance, may have been vaguely influenced by Germanic folklore, but Heroine’s Quest goes all-out by having the heroine interact with the likes of the Norns and the valkyrie Brynhild. You’ll meet Ratatosk the squirrel, travel to Svartalfheim, and possibly even encounter trickster god Loki, who appears decidedly more like a frost giant than his more recognized depiction in Marvel movies.

This Norse setting wasn’t always present in the game. Heroine’s Quest was originally envisioned with a quasi-Celtic fantasy flair, and this early iteration, carrying the subtitle The Legend of Fair Spring, was the brainchild of artist Corby La Croix, who scrapped it and decided to rework the concept after moving to Yellowknife, Canada. Inspired by the snowy landscapes of the region, he teamed up with Pieter Simoons, founder of Crystal Shard and the game’s writer and programmer.

“The Nordic snowy setting was chosen for atmospheric reasons, because Corby wanted to try something new after doing ‘standard’ medieval forest work,” Simoons said in an interview. “Myself, I’m a big mythology fan; I’ve collected books from Greek, Indian, Egyptian, and other myths and legends since I was twelve. So when I started writing characters and puzzles, I took a lot of inspiration from my Norse mythology books. Several of the puzzles come from there, and I rather like that many of the characters and locations can be found in myth books or on Wikipedia. For instance, the character Snorri is named after Snorri Sturluson, who compiled the Prose Edda.”

With Heroine’s Quest’s frigid setting comes survival gameplay that is, once again, more advanced than Quest for Glory’s relatively simple “run out of stamina and you die” mechanic. The first day of the game requires the heroine to venture beyond the city of Fornsigtuna to forage for food and a freezing meter appears in the upper left hand side of the screen, indicating the very real chance that she’ll turn into an icicle if she goes too far. Depending on your character class, you’ll have to turn to warm clothes or fire magic to traverse the wilderness, and the first few days of Heroine’s Quest feel more akin to The Long Dark than Quest for Glory. Some might find the challenge frustrating, but there’s no denying the feeling of accomplishment at seeing your heroine dashing across frigid Jarnvidr with nary a care in the finale, while she could barely leave the city gates in the beginning.

As far as other gameplay mechanics go, Heroine’s Quest offers class-specific methods of achieving goals similar to its inspiration. The warrior can bash monsters, the sorceress wields spells and the rogue cheats. Each class also has specific quests, such as an opponent in the swamp that can only be fought by warriors, a magic mini-game for sorceresses and a thieves’ guild for rogues – who are encouraged to sequence break by stealing major items from NPCs before they’re needed. There’s no secret fourth paladin class a la Quest for Glory, but there is a hidden honor meter, which players can max out to gain access to the flaming sword Balmung, straight out of The Nibelungenlied.

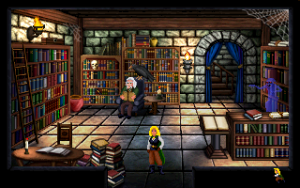

One interesting wrinkle in these class-specific quests (particularly for the rogue, who needs to elude guards while thieving), is the fact that all of the NPCs in the game have their own schedules. While Quest for Glory also did this, it was mostly limited to having the Burgomeister of Quest for Glory IV out by his window during the day and asleep at night. In Heroine’s Quest, NPCs are constantly wandering around the game’s three towns and interacting with other NPCs, with their respective dialogue changing depending on who’s present. There are also a number of optional side quests (including a thought-provoking one featuring a major character who is arguably holding his wife hostage) that can only be completed by observing NPCs in the wild. All of this adds substantially to Heroine’s Quest’s replay value and makes the world of Jarnvidr feel alive to a degree rarely seen in point and click adventure games.

Heroine’s Quest also features Easter eggs aplenty. Characters from not just Quest for Glory but other franchises like Monkey Island will randomly appear in certain screens, and you can temporarily transform yourself into a pixelated sprite reminiscent of those produced by Sierra’s AGI interpreter. At times, the game feels like it’s a love letter to the adventure genre in general, which was a spirit that many Quest for Glory-inspired projects born during the Adventure Game Studio (AGS) craze of the mid-2000s tried to channel. Unfortunately, most of those efforts were cancelled, with Heroine’s Quest standing as one of three survivors. (The other two are Quest for Infamy, by Infamous Adventurers, and the VGA remake of Quest for Glory II, by AGD Interactive.)

Simoons said the tiny group behind the game prevented it from coming down with the bloat that led to the slow demise of other projects. Aside from Simoons, only four others were the primary team members behind the scenes – lead artist Corby La Croix, additional artist and voice director Elissa Ng, composer and sprite artist Dimitrii Zavarotny and composer Matthew Chastney.

Ng added that Simoons’ prior experience as an independent developer was a great aid in ensuring that Heroine’s Quest was actually finished: “A lot of the fan projects were started by people who were well meaning but didn’t really know what they were getting into, and without good direction and someone managing the overall project, things won’t really come together, which leads to loss in motivation. With an inexperienced group, it’s very easy to have lots of ideas. Scope creep can lead to things becoming too overwhelming and unwieldy to manage. And I would say that it’s also sheer doggedness to make sure we saw the project through to completion. We did have dry spells where work wasn’t getting done because of real life commitments, but none of us let it go.”

This doggedness paid off. Following its release, Heroine’s Quest was voted the Best Adventure Game of 2013 during the AGS Awards and even attracted praise from Corey Cole, who said it was “great to see a female-centric heroic quest.” While sequels are currently not planned, Heroine’s Quest remains a loving, self-contained story that is perfect for any Quest for Glory fan hoping for more – not to mention those interested in seeing how a free fan project actually managed to make it through the finish line.