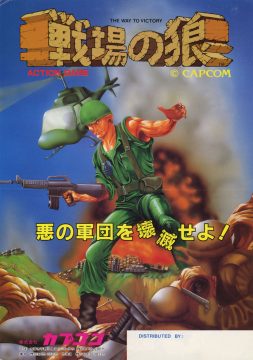

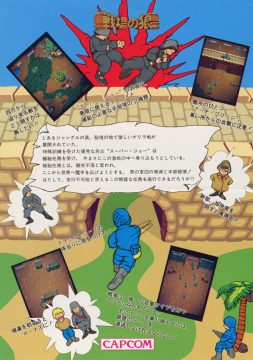

Throughout the late 80s and early 90s, one of the more popular arcade subgenres was the “overhead run-and-gun”. They featured one or two characters, typically men in a military setting but occasionally using other themes – running forward, shooting and/or blowing up everything in site. Though there were overhead action games that preceded it – Taito’s 1982 game Front Line probably being the most evident – the game that popularized the concept, particularly in North America and Europe, is Capcom’s Commando, known in Japan as Senjou no Ookami (“Wolf of the Battlefield”). The game was designed by Tokuro Fujiwara, the ex-Konami designer of many of Capcom’s 80s arcade games.

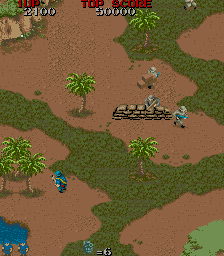

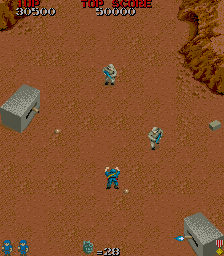

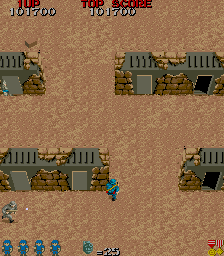

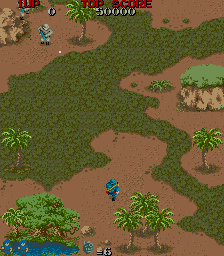

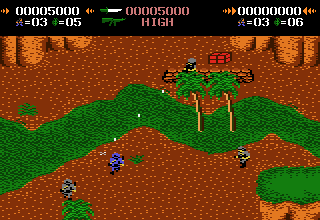

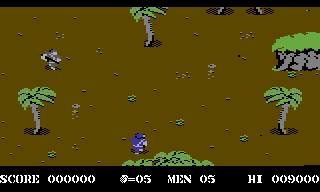

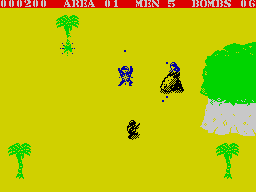

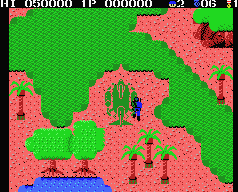

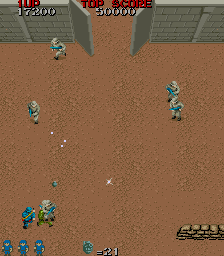

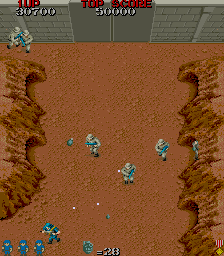

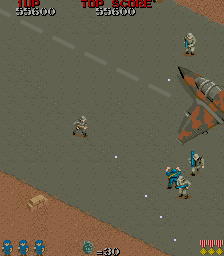

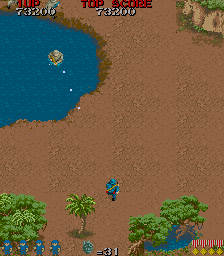

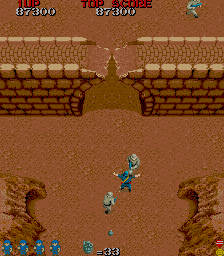

Commando stars Super Joe, a mostly indistinguishable infantry man in a blue outfit, charging forward as he blasts unnamed enemies in a fictional war. Taking place in the nebulous year 19XX (later a title of a Capcom shoot-em-up), the characters are dressed like World War II soldiers, but the setting (the jungle) and level of technology (helicopters) seems more like Vietnam.

This particular subgenre is based on the vertical shoot-em-up, which was extremely popular in Japan in the 80s. The main difference is that you control a human rather than a spaceship, and can therefore advance the screen at yourown pace, rather than the screen autoscrolling. You can also face and fire in eight directions, allowing enemies to attack from all angles.

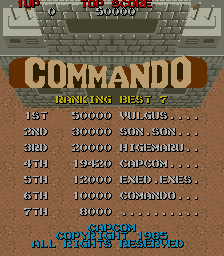

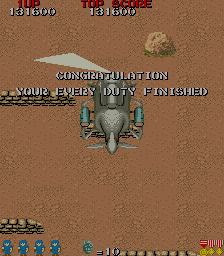

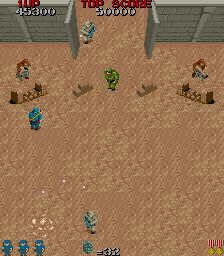

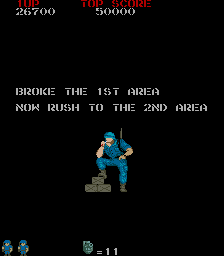

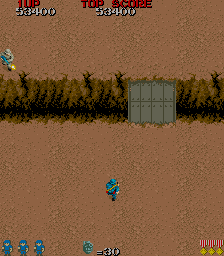

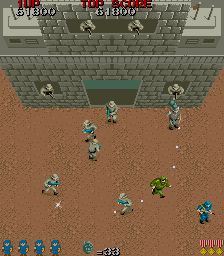

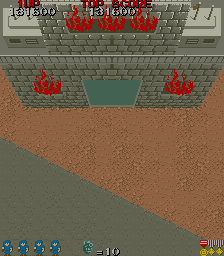

There are a total of eight stages in Commando, divided into two campaigns of four stages each. Most of the levels are punctuated with a brief image of Joe taking a drag of a cigarette or eating some rations, while the stage score is displayed. The concept of boss fights wasn’t exactly common by this point in 1985, so instead there are encounters where the screen stops in front of a gigantic door, and you need to face off against a flood of enemies, until you’re allowed to progress. In the last stage of each campaign, this wall is replaced with a large building, which is summarily torched by the hero once he’s defeated everyone. Then a helicopter picks up Super Joe and ferries him directly into the next stage. After eight stages, the game loops back to the beginning, so there’s no real ending.

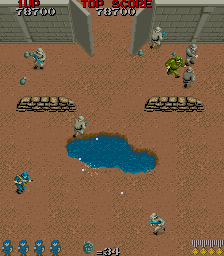

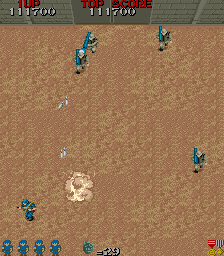

Being that this is the game that basically started this type of subgenre, it’s obviously not very advanced, as the levels are visually repetitive, there are no bonus weapon pick-ups, and again, there aren’t any real boss fights. So most of what you do is run forward, shoot, grab some grenades, and occasionally save prisoners. Yet the game remains enjoyable even today because the fundamentals are extremely well established. A major issue with many early shoot-em-ups is that your default weapon is too weak. That’s not a problem here, because Super Joe’s Machine Gun fires fast and furiously, two bullets per button tap, though they do only travel about half the length of the screen. In addition to the eight directions you can run in, if you turn between them, then the bullets are actually fired in the in-between angles, so you can quickly arc the joystick around to create a thick spread of projectiles. In this way, the lack of power-ups is actually a positive, since the main weapon is just so damned good.

Your secondary weapons are grenades, which are in limited supply. These are much harder to use – they’re always tossed upwards regardless of which direction you’re facing, and they travel a short distance before they explode and do damage, making them hard to aim. They’re not all that useful when attacking regular enemies, but they can hit where your machine gun can’t, including on top of bridges and in trenches, plus it’s really the only useful weapon against vehicles like jeeps. Your supply of grenades isn’t reset when you die either, so you can continue to stockpile them if you don’t use them.

Compared to some other arcade shooters, Commando also isn’t too difficult. You can only take a single hit and are sent back to an earlier checkpoint, but the stages aren’t very long so you’re rarely kicked back very far. The enemies are set up so in many cases you can just charge straightforward without having to stop and fight of them, so the game constantly moves at a brisk pace. The only really challenging parts are the sections where enemy vehicles pop in off the sides of the screen – since there’s no forewarning, you can’t run along the edges because you’ll get immediately killed, so you need to charge down the middle, giving you less space to weave through bad guys.

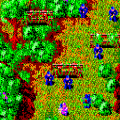

The visuals are mostly green and brown, so it’s not exactly exciting, but the character sprites are well animated. There’s only one piece of music played throughout, a catchy ditty with a military-esque drum beat, that helps define the setting. This is also the first Capcom game to use FM synth, marking a trend of musical excellence that continued well throughout the company’s golden years.

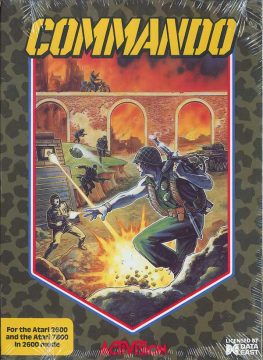

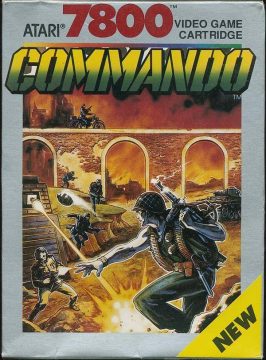

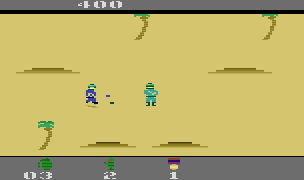

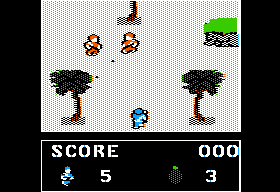

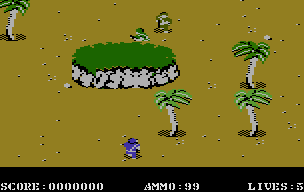

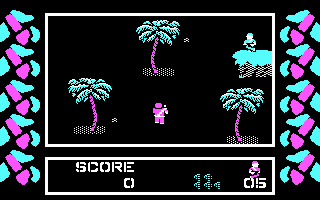

Perhaps one of the reasons Commando made such a huge mark on the gaming audience was the fact that most of the home ports were pretty good, with most of the Western computer versions handled by Elite. Many of them had some kind of compromises – wider playing fields to account for horizontal monitors (compared to the vertical orientation of the arcade), degraded visuals, less enemies or bullets on the screen, slower speed, glitchiness, and awkward commands to toss grenades (either with a key on the keyboard or holding down the fire button. Still, most of these captured the essence of the original arcade game. Even the simplistic ports to the Atari 2600 and Intellivision, released by Activision, were reworked well enough to be playable on their specific hardware despite the hugely downgraded graphics and simplified level designs.

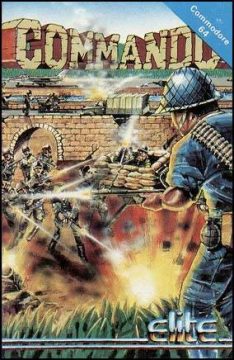

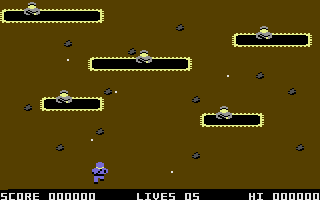

The Commodore 64 version is one of the most well remembered thanks to its excellent remix of the main theme by Rob Hubbard, which was used as the basis for the overhead bonus stages in Bionic Commando Rearmed. The only downside to this port is that it’s only three stages long, so it can be beaten in about five minutes. A version was created for Atari 8-bit computers by Sculptured Software (who also did the Atari 7800 port) and intended for release for the Atarl XL, but was never released. A prototype version was later found and dumped.

The only truly bad ports are the IBM PC version, developed by Quicksilver Software, which is stuck with choppy scrolling, terrible CGA graphics, and haphazard enemy encounters; the Apple II version, with its tiny playing field; and the MSX version, which is so slow as to be unplayable. The Atari ST and Amiga versions are the closest one could get to the arcade for a long time, with extremely faithful graphics, and just differences in the sound. The Japanese PC ports, for the PC88, FM-7, and MSX were published by Ascii.

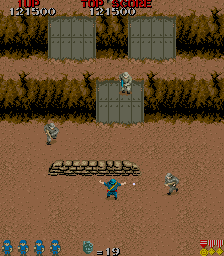

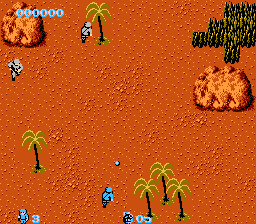

Capcom’s early NES ports were handled by Micronics, which were of mediocre-to-bad quality. Commando was their first in-house project, though it still suffers from some issues. The core action is replicated faithfully, but it’s also insanely glitchy – some of the computer ports had issues with things like collision detection, but the NES game’s programming can just not handle the amount of enemy sprites on the screen, so they constantly just flicker out of existence.

This does, however, mark the beginning of Capcom adding stuff to their home ports. Here, there are hidden underground bunkers, revealed with grenades, that contain power-ups to strengthen your machine gun or grenades. These areas given the game a little more visual variety, and include unique obstacles like snakes and booby traps Fallen enemies drop a wider variety of power-ups, including radios to kill everything the screen, bulletproof vests to absorb hits, and binoculars to reveal the locations of the secret areas. There are also now four campaigns of four stages each, effectively doubling the number of areas from eight to sixteen. Altogether, in spite of the fact that it feels like it’s held together by the digital equivalent of masking tape, it’s still a decent enough conversion.

Germany has famously been sensitive to war games that involved killing human characters, especially ones that looked kinda like Nazis. In the German arcade version, now renamed Space Invasion, Capcom got around this by changing all of the enemy characters into robots. Konami took a similar route with Contra when porting it to the NES, changing it to Probotector in Europe.

Commando also shows up in most Capcom arcade compilations, including Capcom Generation Vol. 4 for the PlayStation and Saturn, Capcom Classics Collection Vol. 1 and Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded for the PSP, and the Capcom Arcade Cabinet for the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. It also appears separately on the Wii Virtual Console, renamed Wolf of the Battlefield: Commando, most likely to tie in with the third game in the series, released around the same time. This new name is only mentioned on the menu though, as no change was actually made to the in-game title screen.

Super Joe went on to have adventures in other Capcom games….kind of. Tokuro Fujisawa’s follow-up to Commando, The Speed Rumbler, starred a character named Top, at least in the Japanese version. For the American version, he was renamed Super Joe. Similarly, in the Japanese arcade version of Bionic Commando (known as Top Secret), the main character was originally unnamed, but changed to Super Joe for the overseas release. Super Joe also appears as a captured soldier in the NES version of Bionic Commando, even in the Japanese release. Commando‘s sequel, Mercs, features a character named Joseph Gibson. Initially it was unclear if this was the same character as Super Joe, but the 2009 Bionic Commando release solidified that they are one and the same, so it this been retroactively applied to the Capcom canon.

Screenshot Comparisons

Komando 2 – ZX Spectrum

Slovakia-based developer Microtech Systems, along with DSA Computer Graphics, made their own illegitimate sequel to Commando for the ZX Spectrum, called Komando II.

It has the same premise of the original, but has a uniquely Eastern Europe twist, in that you’re fighting in irradiated land, so a radiation meter will show how closely you are to death, which acts as a timer. There are also a few small changes to the formula, including extra weapons (a bazooka and a flamethrower), plus colliding with enemies won’t kill you, leaving you only vulnerable to projectiles.