- Bangai-O

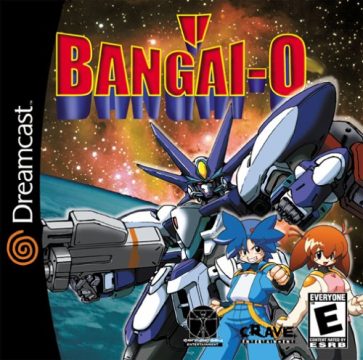

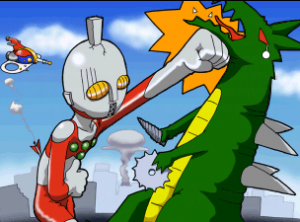

There’s an old saying that “big things come in small packages.” In Treasure’s Bakuretsu Muteki Bangai-O (“Explosive Invincible Bangai-O”, or simply Bangai-O in the English release), you control a robot, just dozen pixels or so in size, which can decimate an entire screen with a single, well-timed attack. It’s a love letter to both Japanese mecha shows (the name itself is a reference to a late 80s OVA called Dangaioh) and old-school computer shooters. Bangai-O combines this classic flavor with a healthy dose of clever game mechanics and fantastic amounts of wanton destruction, both Treasure trademarks.

Each of the 44 levels contains only one real goal – get to the end and get to the boss – but in the meantime, you’re given the opportunity to destroy anything and everything that moves. The control pad pilots the mech, while the C-buttons (in the N64 version) or the face buttons (in the Dreamcast version) controls your firing. In the standard configuration, you can use two attack buttons to enable free movement or fixed shooting, allowing you to lock your fire in a single direction while moving in another. It’s much better to change over to the advance mode, where each of the four face buttons can be used to fire in any of the eight directions, similar to Robotron or any number of dual analog shooters that have shown up on the Xbox Live Arcade. The big difference between Bangai-O and any of these games is that Bangai-O is a side-view shooter – since your mech doesn’t hover on its own, gravity is always pulling you down, requiring much more precision to be able to dodge enemy fire. The Bangai-O has two different pilots – blue haired boy Riki and meek, brown-haired girl Mami. Each has their own projectile – Riki fires homing missiles, which are great for open spaces, and Mami shoots reflecting projectiles that bounce off walls, more useful for enclosed spaces and destroying foes from around corners. You can change between either character with a quick press of a button. Your own bullets will also cancel out any enemy projectiles, which forces you to play defensively as well as offensively.

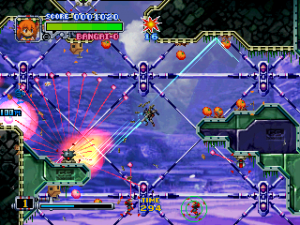

And there’s certainly plenty of enemy fire to dodge. Each level is filled to the brim with other floating mecha, wall mounted missile turrets, wall mounted enemy generators that create an unending supply of enemy mecha, laser guns, and other dangerous obstacles. There’s rarely a moment when you aren’t being assaulted at every angle, which is why the multi-directional shooting in extremely handy.

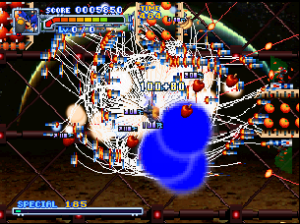

Even more useful than your standard shot is the explosive mega attack. When you use this attack, it will send a number of missiles hurtling in every direction, effectively damaging everything on the screen. And this is the brilliant part – the amount of missiles fired is determined by the proximity of enemy fire. If you’re about to get grazed by an enemy bullet, your firepower will double. If you’re surrounded by bullets which are mere pixels from your ship, you’ll unleash an even larger number of missiles. And if you’re next to a flamethrower and enemies are everywhere and you’re mere milliseconds from getting completely annihilated, a well timed mega attack will trigger a beautiful explosion of 400 missiles flooding the entire screen. It’s an obvious tribute to the “Itano Circus” style of battle scenes – nicknamed after Japanese director, famous for Macross amongst other mecha anime – where dozens upon dozens of missiles fly haphazardly, weaving extensive webs of smoke trails.

The amount of projectiles, combined with all of the other sprites on the screen, usually causes the game to grind to a halt. It’s like a flower of destruction and mayhem, as the projectiles slowly weave their way through the screen, hunting down enemies and exploding, as the game slowly crawls back to its feet and resumes running at full speed. Years and years of video gaming has conditioned us to think that slowdown is a bad thing, caused by haphazard design or lazy programming. Yet in Bangai-O, seeing a Nintendo 64 or Dreamcast – both extremely powerful systems for their time – being brought to a stuttering, sputtering halt by a mere 2D game, is a thing of fantastic glory. This kind of intentional slowdown caused by gigantic explosions and used solely for the effect of pure awesome, has since become a Treasure trademark, and was used to great effect in both Ikaruga and Gradius V.

Some of the stages in Bangai-O are short, but others that take roughly five minutes to complete. Some are fairly open and straightforward – others are tiny mazes, requiring that you hunt down switches to destroy roadblocks. A few stages even require that you set off explosions and rush to the end of a specific area before you become trapped by the resulting rubble. The tiny sprites and large stages emulate the feeling of early 80s computer games, so it comes as no surprise that Bangai-O was originally meant to be a remake of an old Japanese title called Hover Attack (see below). It’s also not an easy game – the first dozens stages or so don’t pose much of a challenge, but the speed and tenacity of the later stages can get quite brutal. It doesn’t help that there’s no invincibility period after taking damage, so it’s a pretty common that a single, focused onslaught of missiles can destroy you in a single hit.

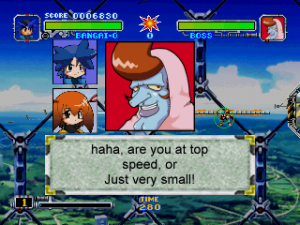

Before each boss encounter, Riki and Mami exchange dialogue with their enemy before fighting. Now, all of the Treasure games have had some kind of goofy sense of humor, but Bangai-O goes totally overboard with the ridiculous speeches. Riki is a nonsense talking goofball, loud and brash like traditional anime mech pilots in the days of old, but without much of a brain. Mami is soft spoken and generally stays in the background. The enemies are just as crazy – one is a sheep who loves to quote from hard boiled pulp fiction novels; another is an evil twin brother who’s jealous that Riki has starred in his own game; one speaks entirely in strange little doodles; and there’s a whole family called the “Core” gang (undoubtedly a reference to the cores found in most bosses in the Gradius series), a bunch of nincompoops who usually sit in place and do nothing. Part of the epic brilliance is due to the English translation, which is so awful it must’ve been intentionally done to emulate the feeling of classic 8-bit games. The writing regularly ignores traditional grammar rules as simple as punctuation and capitalization, yet there’s no part of it that isn’t extremely funny. Each dialogue exchange is also enhanced by the dim-witted background music, which seems to be saying that the game is just as confused by the absurdity as you are.

There’s a lot to love about Bangai-O, but the actual game mechanics differ greatly depending on whether you’re playing the Nintendo 64 or Dreamcast version. The Nintendo 64 version was the first to be released, although only in Japan. In this version, your bullets are pretty weak when you start a stage, and need to be strengthened. The super attack meter is replenished by grabbing fruit from destroyed buildings and enemies, and you can store up to ten explosions at once. If you manage to destroy over 100 objects in a single attack – tracked by a combo meter – a little portal will open up, allowing you to upgrade your bullet’s strength or penetration power, replenish your health, or – if your combo is big enough – obtain temporary invincibility. The amount of items you can purchase depends on the size of your combo – a single upgrade per 100 hits. Your super attack needs to be charged up before it can be used effectively. If you fire it without charging, it will fire about 40 missiles, but if you hold down the button for a few seconds, it will build up to the maximum of 100. You’ll fire additional missiles based off the proximity of enemy fire, as described before.

The Dreamcast version, which was released in America and Europe by Conspiracy Entertainment and Crave, refines a number of the elements for a tighter experience. Your super meter is now filled by destroying objects, be it enemies or scenery, so this essentially makes the fruit useless (although they still give you points.) This means that you can essentially do your super attack infinitely, if you manage to destroy enough bad guys with each attack. However, you can only store five super attacks rather than ten. In addition, the shop is completely gone. Instead, the more objects you destroy with a single hit, the greater likelihood that you’ll find health items or invincibility power-ups amongst the wreckage. The combo meter is gone, replaced by an explosion counter at the top of the screen. Your attacks are stronger by default, so you can’t upgrade them like you could in the N64 version. Additionally, the amount of missiles fired by the super attack is solely dependent on the danger proximity. You can still hold down the button if you want to properly time your assault, but it’s not necessary to charge it up to fire the maximum amount of shots.

There are other minor differences – the life bar is segmented in the N64 version, but it’s one solid bar in the Dreamcast version. Mami’s shots were also changed – in the N64 version, they auto-target enemies after reflecting, and they look like missiles similar to Riki’s attacks. They’re also a bit weaker. In the Dreamcast version, they no longer home in on foes, they’ve been changed to lasers, and they’ve been strengthened so they’re just as strong as Riki’s attacks. The Dreamcast version also has a few extra enemies and structure types. There are some scoring differences too – the N64 version grants you extra points based on the percentage of objects destroyed in the stage, while this is gone from the DC version. The N64 version also gave you increasing amounts of points by gathering a large amount of fruit in a short amount of time, but they give constant values in the Dreamcast version. There are also more characters in the Dreamcast version, and thus, more wacky dialogue.

From a technical perspective, the Dreamcast version is also much better. Although the game is still 2D and runs in low-res 320×240, the backgrounds are significantly more detailed, and the sprites are a bit better looking too. Even the explosions look cooler. There are also many more tilesets in the Dreamcast version. Although most of the levels are structured the same in both version, the backgrounds may look completely different. (The only difference is Level 15, which was completely changed for the DC version.) The Dreamcast version also features higher quality remixed streamed versions of the songs versus the sequenced soundtrack in the N64 version, although neither are particularly great. The Dreamcast version features quick voices clips when taking damage, changing firing modes or using a super attack, as well as other additional sound effects. The Dreamcast version also has quite a bit less slowdown, although it’ll still crawl with the bigger explosions.

There’s a small difference in the Game Over screen between the territories. When you die and continue, you see a bizarre screen of a naked Riki being led through a garden by a ghost. It looks a bit too much like a Ku Klux Klan member in the Japanese version, so it was changed to a strange looking robot for the American version, and they put some clothes on the poor kid. The European version has the same screen as the Japanese one. The ghost has “N64” written on it in the N64 version, and “DC” (obviously) in the Dreamcast version.

It’s kind of a toss up as to which version is actually superior. The Dreamcast version looks, sounds and plays better, plus has the added benefit of being in English. Eliminating the need to upgrade your shots was a good decision, since your bullets were awfully weak in the N64 version, and removing the need to pick up fruit to replenish your gauge makes for a better paced experience. However, the C-buttons on the N64 controls feel a bit better suited for the control scheme than the face buttons on the Dreamcast pad. Either way, you can’t go terribly wrong.

Screenshot Comparisons

[Inspiration] Hover Attack (ホバーアタック) – X1, PC-88, MZ-2500 (1984)

During an interview with Yaiman, one of the directors at Treasure, he revealed that Bangai-O was originally intended to be a remake of an old Japanese computer title, but later took on a life of its own. He didn’t specify the name, but this game is almost definitely Hover Attack, published by a company called Compac. Your goal is to maneuver your mobile base from one side of the level to the other. The base itself is technically defenseless – however, you can send a little jet pack wearing soldier out to eliminate any threats.

Similar to Bangai-O, you move and fire independently of each other – the directional arrows moves your soldier, while the numerical keypad allows you to fire in three directions, either straight ahead or at upward or downward angles. Unfortunately you have both limited ammo and thrusting fuel, so you regularly need to refuel at base unless you want to get destroyed. The missile trails left by all projectiles were another major aspect taken for Bangai-O, which certainly looks pretty impressive for a PC game from 1984. It’s a difficult game to play, because the movement is choppy and it’s too easy to get overwhelmed by enemy fire, but it’s cool to see the game that inspired Treasure’s masterpiece.

The X1 and PC-88 versions can be downloaded here. For those that don’t want to mess around with obscure emulators, there is also a fan remake for Windows available.