It’s not unusual for game companies to promise much more than they can deliver. Throughout the ZX Spectrum era, many companies would start hyping games long before development began. Imagine Software is famous for their vaporware “Megagames”, a pair of heavily advertised titles called Bandersnatch and Psyclapse which allegedly would have pushed the limits of the ZX Spectrum. Revolutionary gameplay and intricate hardware expansions were hinted at in the ads, but these dreams were quickly dispelled when Imagine Entertainment dissolved due to mounting debts. Owing various magazines a surplus of £50,000 in advertising costs, the expensive and overblown hype ruined the company. Also lending to this problem were exorbitant operating expenses, with eighty staff at a time when very small teams like Ultimate Play the Game and Gargoyle Games were making innovative and popular hits for a fraction of the cost.

John Peel, founder of Legend games, greatly respected the products of Ultimate and Gargoyle, even name-dropping them in interviews. This makes sense considering Peel’s home-grown adventure title Valhalla might have had a big influence on both companies’ adventure games.

Peel formed a company called MiCROL in 1981, selling spreadsheet and database software to various companies. MiCROL made a profit, and when he noticed that companies like Quicksilva started heavily advertising Spectrum games around the 1982 Christmas season, Peel felt like there was money to be made. Talking with Sinclair User in late 1985, Peel noted that the newly formed Legend games “decided to go for an adventure as the only professional adventure at that time was The Hobbit.” An interview from Your Spectrum a year earlier also notes the influence of Beam Software’s classic text adventure: “The Hobbit was a milestone in commercial terms, but until Valhalla came along there was nothing new.”

Claims like this make Peel sound very boastful, but at the time, he must have believed his product was that revolutionary. Created by a four man team in a one-bedroom flat in Purley, London between March and October 1983, the Norse myth-themed Valhalla sounds absolutely stunning on paper. A huge, graphical world containing animated characters, NPCs who interacted with each other without player input, and a morality meter that affected character alignment were all unheard of at a time when arcade action was the software status quo.

Still, ideas are ideas, and Valhalla’s ultimate problem is that none of its key elements are particularly well-executed.

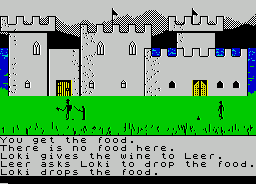

Booting up the game, the player is forced to sit for twenty seconds while the background, items, characters, and text parser are all slowly drawn onto the screen. Legend’s in-house Movisoft graphics engine first draws elements of the background, then the foreground, and then any buildings or bodies of water. Players move between screens using cardinal directions like a text adventure, but any movement requires the program to redraw the next area’s background. If the player wants to quickly move six screens north, they will be waiting a couple minutes to reach their destination.

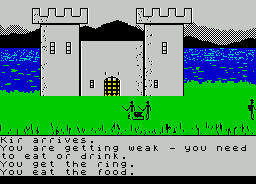

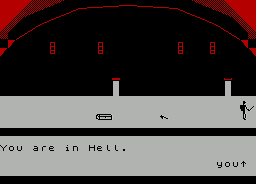

There are eighty-one screens spread across three large sections, although they tend to look the same. Asgard, Midgard, and Hell all contain mountains in the background and grass or water in the front. Sometimes the player will find themselves in a large bland room or a cave system, which looks very plain aside from some stalactites. The game begins at Valheim in Asgard, just outside of the titular Valhalla. Entering this golden hall wins the game, but a variety of items are required to access the building, a scavenger hunt that comprises your entire quest.

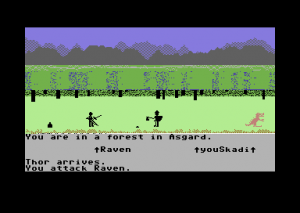

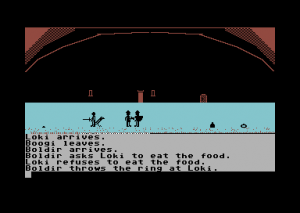

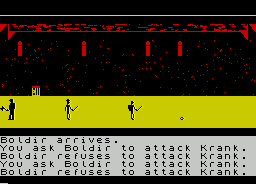

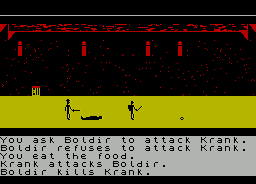

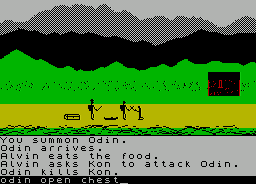

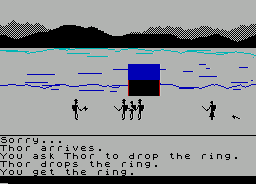

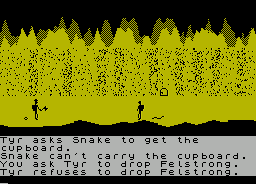

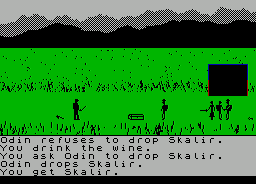

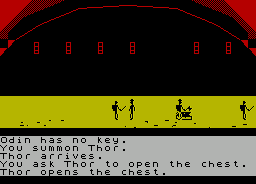

Every screen has a variety of good and evil characters moving about. They’re all simple black figures who walk very, very slow. If you let the game run by itself, characters will start randomly doing things, although only one action can be completed at a time and they often last over half a minute. Odin walks on the screen and then leaves. Thor starts dropping food or giving items to other characters. Saga attacks and kills Glut, who may or may not return ten seconds later since all characters respawn almost immediately. Kon asks Talis to eat her food, but she refuses to. While it’s pretty cool that the game world is continuously running regardless of player input, it’s all very surreal as no one actually says or does anything remotely significant. It’s a whole world made of people arbitrarily fighting and exchanging stuff.

Across the land, items litter the floor. Collectable inventory items are visible onscreen, although they tend to be very small and difficult to identity at first. Aside from the seven main quest items, the player will find food, wine, keys, rings, and weapons. Weapons make it easier to survive battles, keys open chests, and rings allow teleportation on screens where a ringhole is present. The player has very limited inventory space, made even more problematic when the character’s strength is low, rendering them too weak to even lift an object.

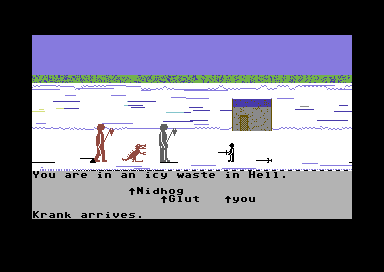

Keeping up your player’s strength throughout quickly becomes the only real threat in Valhalla. Any actions drain a certain amount of strength, and players will need to eat food and drink wine to combat this. Edibles are limited across the land, making it necessary to eventually start buying food from NPCs with krowns, the game’s currency. While you can sell or buy anything for krowns, food is the only item that you’ll eventually need to purchase. If you wait long enough on any screen, somebody will normally appear and randomly drop food anyway, making the in-game economy totally worthless. Starving to death transports the player to a section of Hell fully healed.

Things get interesting as you realize that simple tasks like picking up a shield drastically drains your health. Summoning different characters becomes crucial as you will need other stronger gods or goddesses to accomplish mundane actions like opening chests or cupboards so you won’t die of starvation. NPCs also become important storage units in the later part of the game, juggling key quest items to get through certain areas. To receive aid from NPCs, you need to align yourself with the good guys or the bad guys.

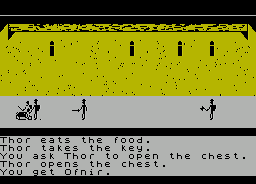

Alignment is very unsophisticated. There’s a set of goodies like Odin and Thor and baddies like Loki and Hel. You can befriend either good or evil people by giving them items. A lot of sources talk about how John Peel and his wife Jan came up with the characters themselves, but none of the NPCs have any personalities outside of their Norse myth names and base statistics. The manual mentions all of these stats without describing what they do: goodness, badness, charisma, strength, bravery, and brains. High strength obviously allows Thor to open more chests for you, but other than that it’s not really obvious what the other stats dictate. Charisma seems to affect item trading, bravery determines how likely characters are to attack others, and brains dictates how smart a character is. Brains definitely has an effect on the gameplay: the intelligent Odin will always hold onto an important quest item if you give it to him, while a total dope like Thor will start giving away your only Ofnir key to random villains. Regardless of alignment, many characters will occasionally refuse to accomplish tasks, forcing you to repeatedly ask Odin to kill Loki or open a cupboard before he agrees.

Enemies can also attack and kill you, but this rarely happens. It’s more likely that Thor or someone with high bravery will start killing off random foes. There’s only a few sections where killing a character is totally necessary to move onward, and battling opponents yourself tends to drain your strength. It’s wiser to summon Odin to kill Krank or any other dangerous enemy than to waste precious resources that could be used picking up an important quest item. Regardless of whether you do take advantage of the battle system, it’s more likely that you’ll die from hunger than the edge of a blade.

The main quest is remarkably straightforward. The player must collect the Ofnir key, the Drapnir ring, the Skornir shield, the Skalir sword, the Felstrong axe, and the Grimnir helmet in that order. The game is largely linear in that possession of the certain quest items is needed to take routes to the next item. An interesting design choice is that some paths will bar you from progressing if you have an item. The Skalir sword might help get you into a certain cave, but it can block you from moving on to the next screen. This forces the player to summon a character, repeatedly ask them to drop their current weapon if they keep refusing as they often do, and then give them the Skalir. After getting through, another path eventually calls for the sword and the player must summon the character again, repeatedly ask the NPC to drop the Skalir, and then retrieve the sword. For most gamers weaned on LucasArts adventures, this would be an infuriating test of patience, but it’s a cool twist that takes advantage of the game’s design.

Perhaps the most bizarre portion of the game is the ending. After getting all of the items and entering Valhalla, every good and evil NPC enters, congratulates the players, and leaves. The whole process takes about ten minutes.

The endgame reflects the entire experience: Valhalla promises big things, but it’s all a strange mess that bores more than it scores. It’s cool that characters can interact with each other, but they’re never really doing anything meaningful. The alignment system is pretty innovative, but friends remain unpredictable and require a minute or two of repeated requests before they finally drop some of their food. All of the animations would look great if the sprites weren’t crude little stick figures who move like snails on molasses. Everything boils down to a very rough and overtly simplistic inventory slog. Still, for a pre-King’s Quest graphic adventure, Valhalla remains pretty unique with its open-world aspects. Being able to kill anyone and anything can be great fun, and seeing what weird things the NPCs will do on autopilot is strangely endearing. If only there were more things to do in the world, Valhalla would have had a sense of freedom that most traditional adventure games lack.

Valhalla was initially met with a warm critical reception. Popular Computing Weekly called it a “living movie”. British Micromputing and the Computer Trade Association gave it Game of the Year awards. Throughout late 1983 and early 1984, Micro Adventurer, Personal Computer News, Sinclair User, Home Computing Weekly, and Crash all gave the game positive reviews, mostly focusing on the graphics. Crash, however, noted the lack of depth and the general empty feeling of the whole game. In May of ’84, Your Sinclair speculated that many of the initials reviewers didn’t play the game. Back then, dozens of computing magazines competited to have the first published review on a big name game, making it likely that journalists only played the game for a few minutes before drawing their final conclusions. Zzap64 labeled Valhalla number one in their list of worst top-sellers in their inaugural issue. A retrospective review in Sinclair User two years later sums up the general consensus: most people think it’s a tedious mess, but Valhalla remains a singular experience that any adventure fan should at least check out.

A Commodore 64 port was developed by Legend and released in early 1985. The background drawing and characters animations remain ridiculously slow, but the sprites are markedly more detailed. Aside from this, the core game play is largely retained.

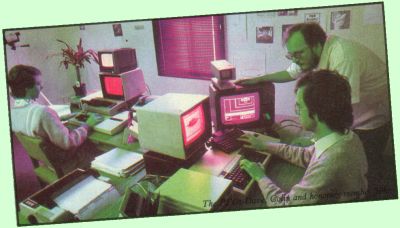

John working with his team circa 1985. By this time, none

of the original Valhalla crew were working at Legend.

John Peel mentioned the possibility of a Valhalla 2, which would have mixed an icon-based interaction system with a text parser, but the company folded before then. In 1984, Legend released The Great Space Race, a space action/RPG game that critically and commercially tanked upon release, losing the company £200,000. After another flop with Komplex, a stuttering Battlezone clone, the company quickly folded the following year.

Two members of the four man development team went on to develop a few more adventure games. Programmer Richard Edwards directed the point-and-click adventure Daughter of the Serpents, while Charles Goodwin would design and program the isometric adventure Warlock for Amstrad CPC and the bizarre James Clavell’s Shogun. Not to be confused with the Infocom text adventure, Shogun is a side-scrolling action/adventure that borrows heavily from Valhalla, even using interaction icons as Valhalla 2 was intended to. The player recruits wandering people to aid him in becoming shogun before other NPCs do, and a simple automatic battle system similar to Valhalla is also present. The design parallels suggest that Goodwin might have had a strong influence on Valhalla’s design, but this is pure speculation.