After the release of their well-liked but undersold debut title Disruptor, Insomniac Games decided to do something completely different for their next project. This was encouraged by various sources from within and abroad: Sony’s desire to have more family-friendly games on the PlayStation, Mark Cerny of Universal Interactive’s suggestion to create a free-roaming 3D platformer, and Insomniac artist Craig Stitt’s interest in making a game about dragons (his favorite fantasy animal). These all pushed a team of extremely talented people to come together and create a great game that not only fulfilled those desires, but pushed the PS1 hardware to previously unexplored places and led to one of the most highly regarded trilogies in 3D platforming: Spyro the Dragon.

In the magical Dragon Worlds, some dragons are being interviewed for a TV documentary when one of them dismisses the threat of foul-tempered troublemaker Gnasty Gnorc. But Gnasty overhears the insults being thrown his way, and casts a pair of spells as payback – one transforms the dragons’ vast collection of gems into various monsters, while the other turns every dragon into statues. However, the spell misses the young, feisty Spyro, who sets out with his dragonfly buddy Sparx to rescue the Dragons, recover the gems and kick Gnasty’s butt.

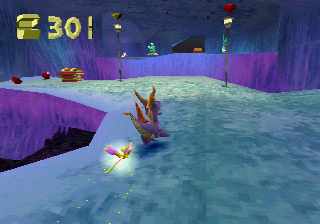

Spyro the Dragon is a 3D platformer where you explore levels and find collectables. As well as the standard running and jumping, you can charge to ram through enemies and chests, and breathe fire in short-ranged spurts. As a young dragon, you can’t fly but you’re able to glide great distances by pressing the jump button in the air. You can also quickly roll to the side, which helps for dodging very quick enemies or projectiles but is otherwise pretty forgettable.

Your dragonfly buddy Sparx acts mainly as your health meter. If you get hurt by an enemy or hazardous pools, Sparx will take damage for you. He can take three hits; changing color with each hit; before he vanishes, leaving you open for a killing blow. Health is replenished by eating butterflies found from attacking harmless ‘fodder’ in each level (sheep, rabbits, etc.). However, Sparx takes a couple of seconds to eat the butterfly, which stops him from collecting gems.

Gems can be found in the open, inside various chests, and from defeating enemies. Sparx will grab any nearby gems for you, and you instantly get them when you charge through a chest. This is a really clever idea, since you don’t need to awkwardly stop to get each one precisely – an issue that often plagues 3D platformers. Dragons are less common, but more important. Stepping on their pedestal frees them, and they’ll give Spyro advice on tackling certain situations, before acting as a checkpoint and save spot afterwards. You’ll also need to find a handful of Dragon Eggs, which have been stolen by hooded thieves who run away and taunt you until you charge them down.

There are six hub worlds, which you can explore and find the level entrances. The first five contain three regular levels, a boss level, and a flight level. Boss levels are the same as a regular level, but with a pitifully easy boss to fight at the end. Flight levels are optional stages where you can now fly anywhere, and have to fly through or flame four types of objects/enemies within a time limit. These levels offer a nice change of pace from the main gameplay that reward you with more gems, though they can be very tricky. To reach the next hub world, you’ll need a certain amount of a collectible. The required collectible changes with each world and the amount needed goes up greatly, which encourages exploring every level for items. The final world only has a few levels where your main goal is to reach the end before taking on Gnasty Gnorc, but that doesn’t mean you should ignore gems and Dragons. If you find everything in the game, a secret will be revealed…

What’s remarkable about Spyro the Dragon is how holistically designed its gameplay is, where nearly every aspect is used to compliment and work towards each other. While other games often have exploration, platforming, collecting and combat feeling segregated through awkward controls or mechanics, Spyro manages to blend them all together so naturally that just about every move has multiple functions. For example, charging is used for moving about, defeating enemies in combat, and collecting gems from chests.

This can also be seen in the enemies, which are famous for how reactive they are. In most platformers up to that point, enemies would either march back and forth or repeat a generic attack, indifferent to the player and the world around them. But in Spyro, enemies move around, fight each other, chase random creatures, and will react to you as soon as you get near – either running away or preparing to attack. This not only gives them a greater sense of personality and character, but it encourages you to chase after them or carefully consider when to attack them – weaving the combat naturally into the other mechanics.

It makes the gameplay feel much more cohesive and satisfying than it would be otherwise, and it’s backed up by superb, responsive controls. Jumping and gliding have an appropriate amount of weight, breathing fire is easy to pull off, charging automatically pushes you forward to let you focus more on steering Spyro, and moving around is a sheer joy thanks to how comfortable it feels. Granted, this flow isn’t always smooth. Some of the chests force you to stop and accomplish a small puzzle before you can get the gems inside, which introduces a stop-start pace that clashes with the rest of the game. Charging has a bit too much understeer when turning, which can send you into a wall or off a cliff without constant adjustments.

Thankfully, this doesn’t detract from how well everything complements each other, and especially the level of freedom you’re given to approach the game. Levels are wide open and have various points of interest and routes, allowing you to explore and collect in all kinds of ways. Because you only need to find a required amount of a collectable, you can tackle levels in any order, or even ignore a couple if you have enough to progress. But because what you need to get changes with each world, you’re subtly prodded to revisit previous levels and try exploring new areas. The flight levels even contribute to this, since you can earn gems from them if you’re having a hard time finding them elsewhere. But this freedom does have a couple of drawbacks. If you’re really into collecting stuff, you can easily find everything on your first go and move on without looking back, which makes the levels less memorable. It also makes the game’s overall structure quite repetitive, since you’re going through the same routine until the end.

However, the levels themselves do a great job at offering up a variety of challenges and complexities. Some stages focus more on exploration, others on combat, and even more on platforming – and they all do so in different ways. They start off simple, before drastically increasing in scope to offer alternate routes and whole chunks that can only be accessed through secret areas, which encourages you to explore as diligently as you can. It’s also a big enough game without any padding. With over 20 levels and all kinds of stuff to collect, you can play it for hours, but the gameplay flow is often so smooth that you can breeze through it if you’re experienced. This makes it equally enjoyable for newcomers and veterans itching for a quick replay.

On gameplay alone, Spyro the Dragon is incredibly solid, but it also earns big points for having great presentation. The most notable example is its graphics, both technically and artistically. The hardware of the PlayStation wasn’t suited to creating the kind of free-roaming 3D platformers you’d find on the Nintendo 64, but programmer Alex Hastings created an engine that could do just that. This is largely thanks to a rendering trick called ‘level-of-detail’. Every level has two different versions; a flat-shaded world with no detail, and one with much more detailed textures and geometry; and fades between them according to your distance to any particular point, so nearby objects have more detail than anything further away. This trick of perspective works wonders for presenting these huge worlds without using a fog effect to hide distant areas, and ensures that things run at a consistent framerate of 30FPS.

Backing this up is a strongly considered use of colors and architecture to naturally draw the eye and make every element easily discernable from each other. The most obvious example of this is Spyro’s distinct purple color. He was originally green, but blended in too well with the grass of the early levels and was given various color schemes until they came across a shade of purple that helped him stand out in any environment. But this also extends to the rest of the game. Gems come in a variety of colors, and have a sparkle that can be seen from anywhere so they can be found more easily. Every level features its own environment, unique geometry/landmarks, and gorgeously impressionist skybox – and each of those uses a unique color palette that gives the world a distinct mood that stands out just as much in the players’ mind as much as they stand apart from other worlds.

Perhaps the only place where the visuals slip up are in its character designs. Spyro’s design (done by Charles Zembillas, who created the character designs and world aesthetic for Crash Bandicoot with Joe Pearson) is charming and well animated, but everyone else isn’t as good. Dragons often look too similar and generic, while enemies are vaguely defined and not as expressive as Spyro.

Just as memorable is the soundtrack by Stewart Copeland, the drummer for The Police and a fairly prolific composer at the time (Highlander II, Wall Street, The Equalizer). This was his first time doing music for video games, and he went into it with gusto – playing the levels vigorously to figure out what music would fit each one (something Insomniac weren’t aware of, since they placed the tracks differently from what Copeland intended). While he was used to the hectic nature of creating soundtracks quickly, Copeland once likened doing the music to Spyro as doing a quadruple LP of backing tracks, and recalls creating three tracks every day. This means every level has its own unique music track, which helps to give each one a memorable atmosphere.

Using his influences such as reggae and rocksteady, along with a wide set of instruments including crotales, power guitars and drawbar organs, Copeland created a very distinct soundtrack in terms of composition and instrumentation. For many tracks, there’s a strong focus on rock that energizes the gameplay, while other tracks aim towards a sense of ambience or tension that makes levels more imposing – and they’re all tied together by a melodic sensibility that ensures playing and exploring doesn’t get tedious. Perhaps the only issue is that the music can occasionally sound a bit repetitive, with little change in the compositional style and instruments used between tracks.

Rescuing dragons results in cutscenes where Spyro talks to the dragons, which are fully written, animated and voiced. Spyro is voiced by Carlos Alazraqui, who also voiced the Taco Bell Chihuahua and Rocko from Rocko’s Modern Life, while the dragons are voiced by Clancy Brown, Michael Gough, Jamie Alcroft and Michael Connor. The voice acting is decent enough, but they don’t do much to stop the scenes from feeling awkwardly written and directed.

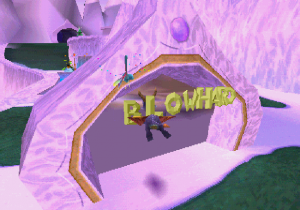

Spyro the Dragon was also released in Japan, which wouldn’t be too unusual except that this version makes numerous changes to both the aesthetics and the gameplay. The font has been mostly changed from the animated golden letters to a flatter yellow typeface (your HUD still sports the original font). Levels and bosses have brand new names, along with a Mario-styled world-level suffix of 1-1, 1-2, etc. The new names are largely descriptive and bland, though the highlight has to be the first boss Toasty’s hilariously weird “Wonder Pumpkin”.

A particular focus was made towards making the game more kid-friendly. Spyro has a much cuter voice courtesy of Akiko Yajima (a seasoned voice actress best known for voicing Shinnosuke Nohara in the Crayon Shin-chan anime from 1992 to 2018), and he makes little noises on occasion when he jumps, charges, glides, or dies; he even exclaims a cheerful “Yatta!” when you find everything in a level. Signposts are liberally dotted around the stages, which stop the game to give you hints and instructions whenever you breathe fire on them. Considering how many signs there are and how often you’re breathing fire, this gets very annoying very quickly.

Weirdly, Sparx is now green instead of yellow and stays green. The only way you can tell the state of your health is that his trail changes whenever you get hit, which is too subtle to be noticed most of the time. This change seems to have been made so he can stand out from the variety of dragonflies that feature in this version of the game. Dragonflies are found in dragonfly eggs, which are bonus collectibles that can only be acquired if you happen to have the PocketStation: a Japan-exclusive peripheral that, when connected one of the memory card slots, could use the data off certain games to play VMU-styled minigames. There’s an egg hidden in nearly every level, and finding it will unlock a dragonfly that you can raise, train, fight, and breed through the PocketStation like Tamagotchis. The only benefit the dragonflies have in-game is that some of them give Spyro extra hit points.

The gameplay has gotten the most changes. Spyro moves much more slowly, with his charge speed being roughly as fast as walking in the original game. It’s also considerably harder to turn while charging, which makes catching thieves or going in a new direction more annoying. The most infamous change is the camera, which is dramatically pulled back and doesn’t directly follow Spyro. It doesn’t rise with you when you jump, and it doesn’t pull up close to you when charging. This was supposedly done to reduce the risk of motion sickness, but it comes at the cost of making the game much less enjoyable.

Navigating and platforming are made harder by the distant perspective obscuring your view, or snagging on chunks of the environment. The downward angle makes higher areas harder to see and leaves you open to attacks. It’s telling how bad the camera is that the game frequently has to cheat its own system in order to work. It cuts away when you fall into a room or use a rising whirlwind, and automatically moves to follow you whenever you go into a tunnel or an area too small for the camera to operate normally. This is really distracting, and made worse by how the camera often cuts to angles where you can’t see anything in front of you.

Curiously, there is a “Director’s Cut mode”, which allows you to play with Spyro’s original controls by pressing L1 and R1 in the pause menu. But you can only do this after you 100% the game, which is pretty outrageous given how much there is to do. Perhaps the longest lasting impact of the Japanese version is how Spyro’s name was written in stylized katakana, which Insomniac read as “Ripto” – a name they’d use for the villain in the next Spyro game, Ripto’s Rage.

(Screenshots of the Dragonfly Eggs and the PocketStation game were sourced from the Spyro Wiki: https://spyro.fandom.com/wiki/Main_Page)

LINKS:

A three page article by Craig Stitt and John Fiorito about the use of color theory and overall art direction in the original trilogy: https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/131581/lessons_in_color_theory_for_spyro_.php

A PlayStation Underground feature examining Stewart Copeland’s process in creating the music: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Kc2gGycBXc

Screenshot Comparisons