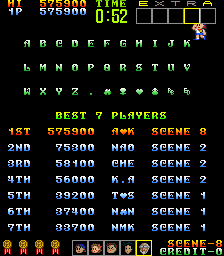

Nihon Maicom Kaihatsu (NMK) is a relatively unknown developer that produced mostly semi-obscure titles, such as Arkista’s Ring and Ninja Crusaders on the NES, and the Rolan’s Curse games for Game Boy. While none of their games are particularly revolutionary, many of them have an interesting hook or unusual structure. In 1987, they developed a pair of games starring five espers – four psychic kids and an old man – that are no exception to these tenets. There are two seemingly small elements that make each of these titles stand out, the first of which being the height of your jump, which is easily enough to make the hero or heroine of most any platformer jealous. The second element is how the player needs to effectively manage each character’s strengths, building a sense of teamwork not often felt in a single-player game. NMK was formed by former staff members of Tehkan (later Tecmo), who previously worked on Bomb Jack, so this game has some elements from that title.

Characters

For some unknown reason, the developers decided to change the names of the characters between the Arcade and Famicom games. To the left are the names as they appear on the arcade flyer, followed by the Famicom names. In the descriptions, the Esper Boukentai names are used.

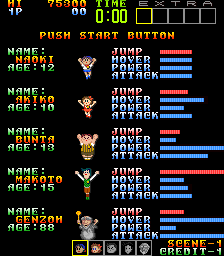

Naoki / Akio

The average, well-rounded character, in case the backwards baseball cap didn’t make that obvious. Although Akio doesn’t excel at anything, he is a good choice for most situations. In Psychic 5, he has the added benefit of being able to traverse narrow passages. In Esper Bōkentai, it’s rare that you’ll need to use anyone else, since he is the fastest, and there are no doors to push.

Akiko / Mako

The “girl” character, who is, unsurprisingly, a slight variation of Akio. Her main benefit is that she excels at hovering, which is far more useful in Psychic 5, due to the numerous ground hazards. In Esper Bōkentai, her long hover is only hypothetically useful, since no parts of the castle are designed to need it to reach new areas, and unless her level is very high, her attack power is too pathetic to make her worthwhile in combat.

Bunta / Genta

This guy is the bruiser, and as such, his talent is strength. In Psychic 5, this is represented by great proficiency in pushing down doors and a moderate increase in attack power, whereas in Esper Bōkentai, the door pushing is replaced by a very high defense value. Unsurprisingly, he’s a poor jumper and even worse at hovering. This makes him fairly useless in Esper Bōkentai, where he is best used in ground combat or as a damage sponge, though only he can break certain walls.

Makoto / Naoyuki

The tall, slender, Luigi-like (he’s even clad in green) character. Most of his stats are about average, but his jump is so high that it’s almost game-breaking. He is useful for making tricky platforming sections much easier in Psychic 5, but in Esper Bōkentai, he is rarely used, unless you’re under-leveled.

Genzoh / Bunzoh

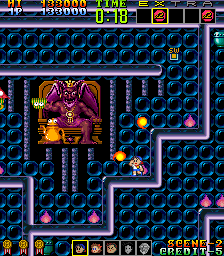

The old man clad in robes, who is simultaneously the best and worst character. He is incredibly powerful, but painfully slow, and cannot jump very high, making him best suited for fighting Satan in both games. To his benefit, his descent is also very slow; his hover is very slightly less than Mako’s in Esper Bōkentai, and in Psychic 5, his hover is so long that at first, it seems like he may never descend.

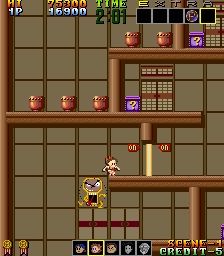

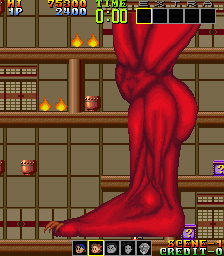

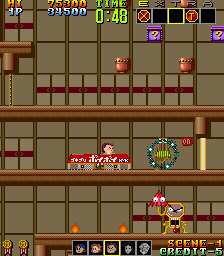

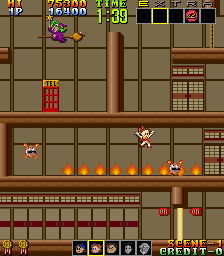

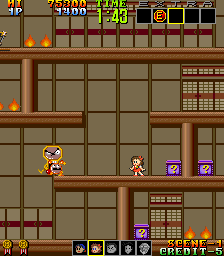

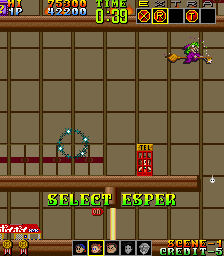

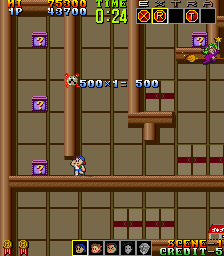

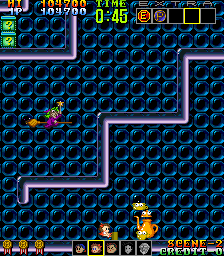

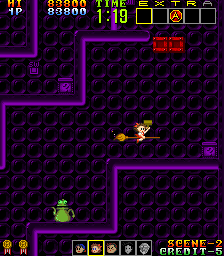

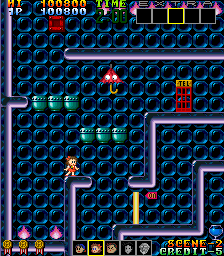

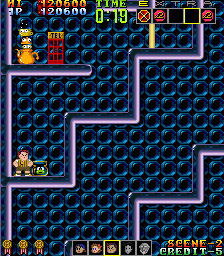

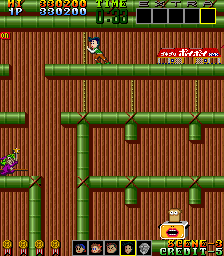

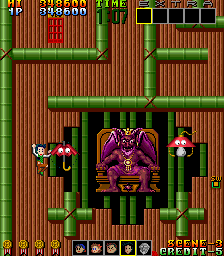

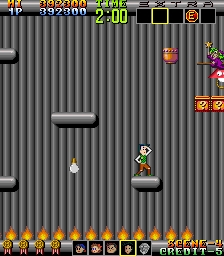

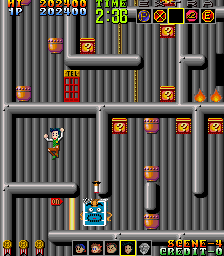

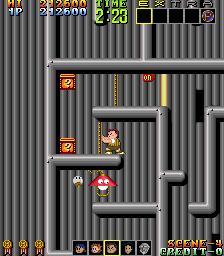

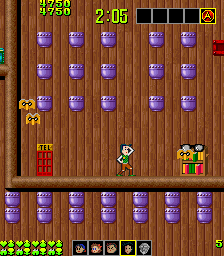

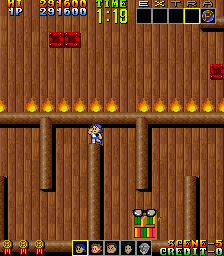

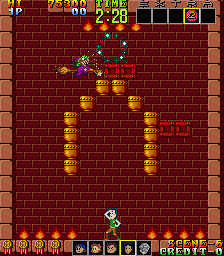

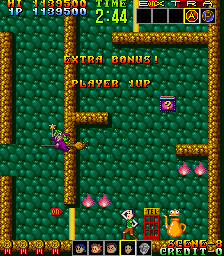

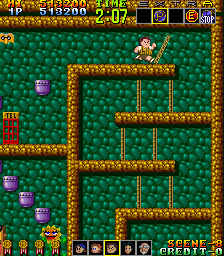

On the surface, Psychic 5 seems to be a pretty typical Arcade Platformer for its time. As soon as you put in your first quarter, you’re taken to a screen that shows five characters, each with their own parameters – some jump higher, some hover longer, some are stronger, etc. – but you are only able to select from two of them. To acquire the others, you have to smash a small glass jar emblazoned with a frog that bears a striking resemblance to Sanrio’s Keroppi. You select your esper before each stage, then navigate the small labyrinth, smashing things with a hammer in order to progress to the center, where you fight the stage’s boss. Along the way, there are pots with food, which provide points, and chests with items. Also of note are the phone booths sprinkled throughout each stage, which allow you to cycle through the playable characters that you’ve unlocked thus far. Colliding with an enemy or flames will kill you instantly, and if the clock reaches zero, a gigantic demon’s foot comes down to squash you.

It’s all pretty standard in structure but unusually wacky in presentation. The backgrounds are fairly realistic in tone, and very typical for the late 1980s, but they have a strong dichotomy with the cartoony enemies. A strong visual characteristic of Psychic 5 and its successor is that your enemies are, by and large, usually inanimate objects with exaggerated facial features.

The first thing that sets the gameplay apart is the jumping. It’s not at all uncommon for video game characters to be able to jump much higher than any real life human conceivably could, but Psychic 5 takes it way over the top. It almost seems a little out of place, and to make it even more ridiculous, you can hold up as you jump to ascend even higher, and continue to hold it to greatly slow your descent. This works extremely well with the platforming elements, especially since you can hold down to jump lower than usual, but aerial combat can become a bit awkward, especially if you’re using someone with a lower hover parameter, because you just seem to keep passing by your target both on the way up and on the way back down. The boss of each stage, Satan, is always in the air, but he is stationary, so it becomes less of a problem with him, though avoiding his fireballs is still pretty tricky.

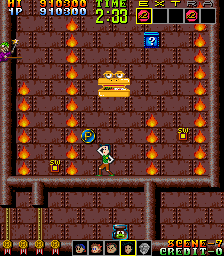

The level design also complements both of the stand-out elements quite nicely. For one thing, it does a good job of dropping hints about which character you should use next; if you see a bunch of doors, you know to use Bunta, or if you see a long vertical stretch, you know that Makoto is your best choice. It even lets you know which character to use against Satan. In general, it’s best to go with a strong character, but they’re not very good jumpers. Most boss chambers are placed in such a way that you can see a fair amount of what’s inside as you progress through the level, so you’ll know whether you need a high jumper, a long floater, or whether strength will suffice.

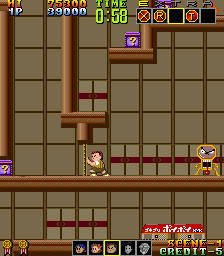

The level design also has its share of oddities. There are obstacles like hidden trap doors, invisible platforms that come into existence when you touch them, breakable walls, and little structures that slow you and prevent you from jumping – they look like fast food restaurants, but are apparently supposed to be roach motels – but in execution, these elements are nothing out of the ordinary. A bit stranger are the light switches, which temporarily make everything but the sprite layer go black, but also make the fires go out, so rather than being just a straight trap, this one offers a bit of a trade-off.

Enemy spawns can also be manipulated; the stages are divided into invisible zones, and entering them makes certain enemies disappear and others spawn, which can be exploited to get by them in certain cases. Really bizarre are the doors throughout the levels, which divide the rooms and give your timer a little boost the first time they’re entered. Little checkpoints that add time to your clock are not uncommon in arcade games of the era – OutRun had those between areas – but these are odd in that you have to jump to open them. The taller characters, however, do not need to jump; it seems that the designers were making sure that the character in question could reach an invisible door knob, which is great attention to detail, but its inclusion here is just… strange.

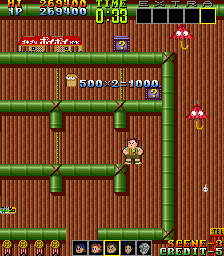

Stranger still is the system by which power-ups are acquired and used. In most any game of this sort, you pick up an item and its effect is immediately activated. Some items still do immediately take effect, such as extra lives, timer boosts, and anything that gives you points. The invincibility is immediate, too: Clobber Zara, the witch that’s constantly hounding you, and you’ll begin flying on a broom, swinging your hammer Donkey Kong style, until the jingle ends and you’re sent back to the realm of gravity again.

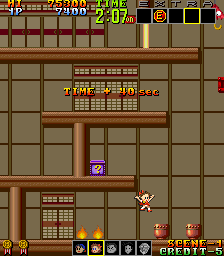

All other items are known as icons, and include score multipliers, power-ups that greatly boost all of your parameters, a time freeze for all enemies, and even letters that spell EXTRA to net you an extra life, not unlike spelling EXTEND in Bubble Bobble. When you grab icons, they just appear in one of the five boxes at the top of the screen. One of these boxes is always highlighted, with said highlight constantly cycling through them. In order to use an icon, you must smash a chest or breakable wall when the box containing it is highlighted. Complicated as it is, this skill must be mastered in order to do well at the game, since icons are generally the most useful power-ups.

Though Psychic 5 is an extremely short game, learning how it works is a gradual process, and this is the greatest portion of its replay value is derived from. Your first run will likely be spent learning strategies for most efficiently getting past enemies and obstacles to keep the dreaded timer from ending your game. If all you set out to do is beat the game, then the timer is not too much of an issue; you have more than enough time to make your way through all of the hazards, perhaps even grabbing a fair number of goodies as you go. This provides opportunity to get accustomed to the basics.

Learning when to use each character is a very important lesson. Utilizing each character’s strengths is essential, whether using Bunta’s incredible strength to push down doors, Makoto’s absurd jump height to reach otherwise inaccessible areas, Bunta and Genzoh’s high damage output to crush legions of enemies, Akiko and Genzoh’s lengthy hover to cross long stretches of fire, or Naoki and Akiko’s small size to fit through otherwise inaccessible passages. In much the same respect, you must also be mindful of each character’s weaknesses; Genzoh, for example, has the strongest attack and the longest hover, but is painfully slow in everything that he does and cannot jump very high. Since you cannot switch on the fly, weighing the espers’ strengths and weaknesses is essential to bridging the gap between phone booths.

The game hammers home this sense of teamwork with the music. It is not the stage that determines the music, but the character used. Each has their own theme, which helps to define the characters, whether it be Naoki’s adventurous tune, Bunta’s heavy music, or Genzoh’s silly melody. Once you get to the boss of the stage, the music changes into his theme, musically uniting the heroes against their common enemy. The songs, composed by Shinichi Sakamoto, who would later go on to compose music for the Wonder Boy games, have a deep, bass-filled FM sound to them that possesses a great deal of impact that’s often relegated to a more typical 8-bit style of chiptune.

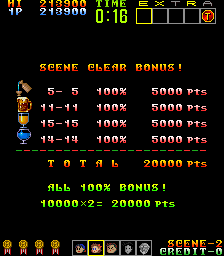

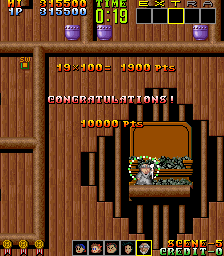

Despite all of this, merely surviving the game makes for an interesting, yet forgettable experience. The game was released in 1987, and while getting a high score was no longer the only purpose of playing a game, in many cases it was still an important part of the experience, and Psychic 5 derives most of its complexity from the scoring. As previously stated, you will have more than enough time to just blaze through each stage, but getting a high score requires grabbing every single food pot in a very specific way, and doing so makes the race against the clock a great deal more frantic. Each food item is inherently worth only 100 points, but will increase by another 100 each time you grab the same food item consecutively. Every time you swing your hammer without hitting a food pot, though, this changes the contents. The food will cycle through all of the different types with each swing, so the idea is to either use the hammer only on food pots or to keep count of your “misses” and how many of each type remain, and totals are wildly inconsistent.

For example, in the second stage, the food items are sake, (root?) beer, orange juice, and a blue liquid (we’ll call it water). When you begin the stage, every food pot will contain sake, but the first time you swing your hammer without hitting a food pot, their contents will all shift to beer, and so it will cycle until it comes back to sake again. Now, rather than all having the same total, there are 5 sake, 11 beer, 15 orange juice and 14 water, so you need to know that and keep track of it, because it’s not practical to just refrain from attacking the whole time. If you happen to get all 5 sake consecutively, that item will give you a Gold Bonus, which greatly increases your score, and doing so for each item in a stage will give you the All Gold Bonus, which is how you really rack up a high score. It’s even better if you manage to take out Zara – you’re flying and constantly swinging your hammer, but that doesn’t affect the contents of the pots, so you can just blaze through them all, racking up unreal bonuses.

It doesn’t end there, either: There’s a Magical Bonus that sometimes hides in jars instead of espers, but there is a way to manipulate where they show up by meeting certain conditions to make the espers show up early, netting you a consecutive boost for the Magical Bonuses, as well. Beyond even that are the large enemies, which generate smaller enemies; killing the large enemy will give you an extra bonus for each alive small enemy that it generated. There are so many different kinds of bonuses to find, but the beauty of it is that they all have the common element of consecutive acquisition, so they’re not so obtuse that the player will never figure them out when paying attention. The Secret Bonus is the only notable exception to this; it always appears in the same chest in each stage, but will not always appear. In order to acquire it, the thousands digit in your score has to be the number of secret bonuses you’ve gotten thus far, so if it happens to be your first, the thousands should be zero. This one is pretty difficult to figure out without help, but it is called the Secret Bonus, so it was probably meant to be that way.

So, while Psychic 5 seems like a pretty standard arcade action title with a few quirks and can be played that way, it has a surprising level of depth for those who choose to pursue the high score hunt. It has a strong sense of layered gameplay that isn’t commonly found in games; the more you play it, the more mysteries begin to form and unravel, not unlike Kid Icarus on the NES. You can certainly try to grasp it all and get every bonus on your first play, but it will likely end in failure. It is in this unraveling that the game develops over time; Psychic 5 wants its players to ease their way into the rabbit hole, rather than tie sandbags to their feet and plummet straight to the bottom. This is also a fantastic way to add replay value to the game; those who just want to get through the game can do so without being punished by missing out on content, but those who really enjoy the game and want more out of it can find just that.

Links:

Psychic 5 – Strategy Wiki A webpage describing the game’s mechanics, namely how the bonuses work.

Playtown Denei An old Geocities site that has some information about the game. May be unreadable due to a lack of character set connectivity.

Game FAQs The walkthrough I wrote from scratch for Esper Bōkentai, which was also used on Strategy Wiki’s page.