1988 and 1989 were very strange years for video games. For whatever reason, this period saw an odd rise in occult-themed games. Taboo: The Sixth Sense, Tarot, Chuugoku Senesijutsu, and ’89 Dennou Kyuusei Uranai all saw release within this specific timeframe. But this article isn’t about any of those games. It’s about Mindseeker, Namco’s psychic simulator released around the same time. Like its peers, Mindseeker isn’t a good game. What separates this title from the rest, though, is how uniquely awful it is. How could a game like this fail so badly? How is it that it fails to understand what makes being psychic so cool? How does a game about controlling the world with your mind end up so thoroughly dull?

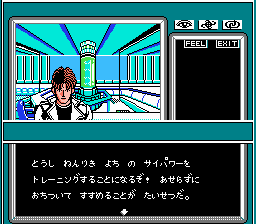

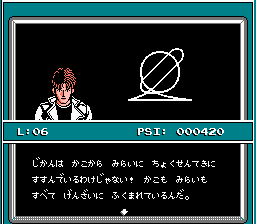

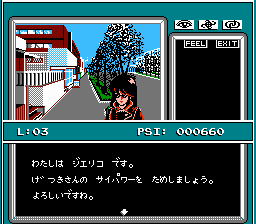

Now that’s not to say that Mindseeker is a complete failure. One of the things the game has going for it is its enthusiasm. From its first moments, Mindseeker demonstrates an uncanny zeal for its fantasy. You start the game attending a psychic academy before your instructor lets you out into the real world to hone your psychokinetic reflexes. All the while, Mindseeker does its very best to convince you that psychic powers are real. Never once does it acknowledge the fourth wall. All its advice about how to play the game is to focus your psychic energy on the task at hand.

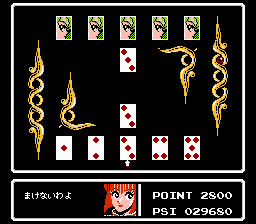

Does this make the game look silly? Yes. But it’s silly in all the right ways. It’s that overzealous tone that makes Mindseeker more enjoyable than it has any right to be. This only becomes more apparent with time, as your teacher starts singing the praises of a future where we realize that time is an illusion, make contact with alien life, and melt into a single existence. What’s more, the game is well researched in some places. Those cards you choose from in the training mode? A slight variation on the Zener cards used in ESP experiments from the 1930s. When the game’s so excited about even its tiniest parts, it’s hard not to be excited along with it.

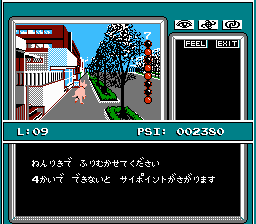

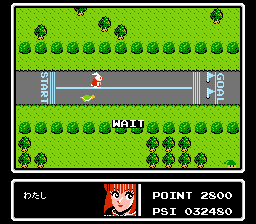

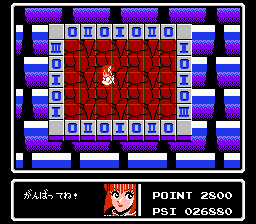

That’s more than can be said about the gameplay. On first glance, the game looks like an adventure game, a genre known for its tight structure and logical progression. Mindseeker can profess neither. Instead, you listlessly wander between three or four places in the city, searching out opportunities to show off your psychic prowess. Said opportunities are always some kind of guessing game, on an activity where you time your button presses to an unknown rhythm. You can probably see the issue with the game already: it’s almost entirely based on luck. You don’t get any opportunities for control because every activity is such a thinly veiled instance of randomly generated numbers.

While that’s certainly bad on its own terms, it becomes noticeably worse in context. The whole psychic fantasy that Mindseeker relies on rests on the idea of control; of having access to this level of reality that normal people aren’t aware of. Unfortunately, little if any of Mindseeker‘s content reflects that. The narrative is partly to blame for this. Every character you encounter is aware of ESP (thus normalizing it), and most of them are willing to let you try the same task eight or so times until you finally get it right. Yet so much more of the blame rests with the game design itself. By basing its activities so heavily on luck, the game erases any shred of credibility in the psychic fantasy. It says a lot about your supposed psychic powers that there’s a casino just down the street from your esper academy.

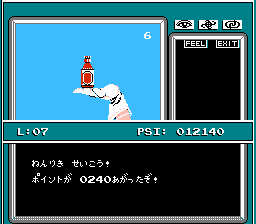

Yet even if the game allowed you some modicum of control, what sort of fantasy would it be representing? What do you actually do with your powers? You guess what number somebody’s thinking of. You use your ESP to make a fountain spray water. You guess what color car is going to come around the corner. Feats like this are closer to cheap parlor tricks than they are to psychic mastery. In fact, they’re barely even parlor tricks. You’re rarely influencing the world in any way; only predicting what will happen from a very limited set of choices. What’s so impressive about that? Granted, your abilities scale as you power up. You move from bending spoons to calling people over to you with your mind to teleporting small objects to/from somebody’s hand. Yet seeing how the mechanics don’t change to reflect that, the game remains as unimpressive as ever. At this point, the whole psychic fantasy is starting to look less like a coherent argument, and more like a cheap excuse for lazy game design.

With the paranormal ideas failing to hold water, the game has nothing to fall back on except tedium. Mindseeker is nothing if not a slow, repetitive, frustrating grind with nothing to break it up. Well, OK, there are random people on the street, but they hardly count. They give you the same activities as before, but with the added possibility of losing your psychic EXP and playing the game even longer. (You don’t lose much, mind you, but it’s still pretty frustrating.) The game also has limited multiplayer capability, in case you don’t want to suffer alone.

While there might be some skill to playing the game, it’s never obvious how. The game itself suggests that timing is a factor, but in relation to what isn’t apparent. It can’t be the music; the same beat can count both for and against the task at hand. Perhaps the clearest answer comes from this tool-assisted speedrun, which suggests you can complete challenges faster by timing your button presses within a two-frame window. Yet seeing how that’s almost certainly a glitch (that still doesn’t apply to the guessing games Mindseeker passes off as psychic), that answer provides very little solace.

Going back to the game’s historical context, a lot of its problems come from fashioning itself as a game. Other occult-themed games sold themselves more as toys than anything else. Doing so allowed them a certain degree of malleability that Mindseeker lacks. By splitting the difference between adventure game and esper training, the game fails miserably at both. It fails the game part because you have very little control over anything, and it fails the psychic part for the same reason. It can’t even be appreciated as a toy. The best Mindseeker can hope for is being a historical curiosity.

Links:

Nico Video Mindseeker TAS

Geocities.JP Detailed overview of the game (with a look at the multiplayer)