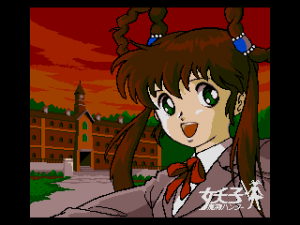

One of the most pleasant surprises one has playing video games is encountering a game that’s unaware of its own potential. The game’s ignorance regarding what makes it so fascinating lends the experience an air of humility that lets its achievements stand on their own. That’s certainly what makes Mamono Hunter Yohko: Dai 7 no Keishou (“Devil Hunter Yohko: The 7 Warning Bells”) such a compelling game. A Valis-esque action game for the Mega Drive from obscure developer Klon, it’s a tie-in to the 90s anime, one which might seem slapped together at first but reveals more character underneath.

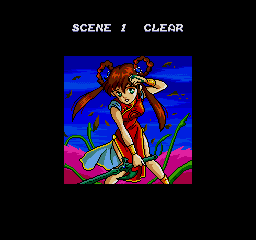

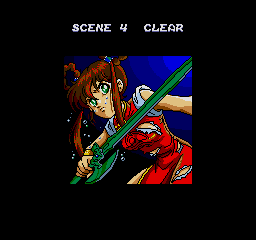

Devil Hunter Yohko, of course, was a response to the “magical girl” craze popularized by Sailor Moon (though the trope existed long before). While that series, as with most, was aimed at girls and young women, Devil Hunter Yohko was plainly aimed towards older boys and men, being a darker anime with substantially more violence and nudity. The heroine is an everyday girl, who maintains her family’s professions as a demon slayer, and fights them in a stylish red Chinese dress. For a game based on an anime, there’s little in the way of cutscenes, just brief images that open the game and close out each level, without even any dialogue.

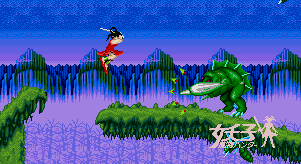

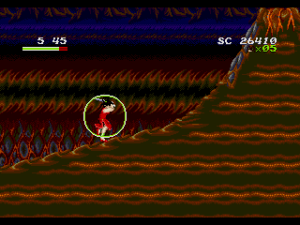

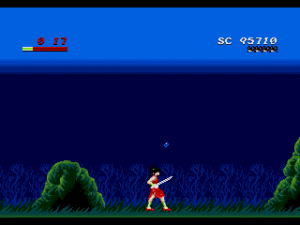

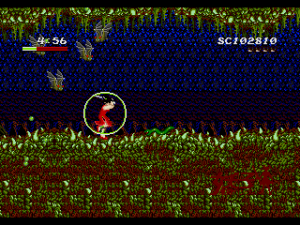

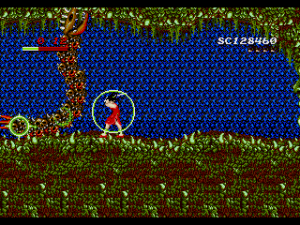

Despite its disinterest in telling a story, the game certainly looks like Valis, or any other Telenet/Wolf Team-developer titles, right down to the featureless face of the heroine. And like many of their titles, it doesn’t feel right either, with slghtly awkward controls and monotonous levels that don’t really develop so much as meander (though there are some branching paths). For example, the first stage is filled with winding vines, but it’s not entirely clear what parts you can walk on until you try them out. Neither the enemies nor Yohko react much to damage – in fact, taking hits is a little bizarre, because there is no invincibility period, but if you manage to avoid another attack for a second or so, Yohko will regain a slight amount of health. It’s not much, though, and you can still find yourself dying in three or so hits.

In spite of its clumsiness, the game remains playable (and quite fun) thanks to Yohko’s sword. She swings it in a downwards arc, which is short ranged, but since it can also absorb almost any projectile, it can be used to ward off most types of enemy bullets. More direct is the charge shield, activated by holding down the button, which will similarly protect Yohko from bullets. It will also quickly regenerate once something penetrates it, though it’s pretty much useless against the many enemies that will fling themselves at you (or use other attacks like fire). The shield is also a weapon though – let go of the button and she’ll fling it like a boomerang, able to be aimed in various directions (though not straight up or down, curiously). It’s not too strong, as you’ll still need melee attacks to really inflict damage.

Yet neither the source material nor the action explain Mamono Hunter Yohko’s appeal. What makes the game work its capacity for cruelty: the many elegant ways it imparts a foreboding sense of dread through play.

Curiously, the game abandons the pursuit of power that characterizes similar games. If anything, their only purpose is to undermine it. Yohko’s clumsy swordsmanship, for example – if you hit the button too fast, she’ll stop mid-swing and start over, making it extremely ineffective unless you time your hits right – stifles any feeling of accomplishment one might get from fending off the various monsters that populate the levels. And the levels themselves are barely more forgiving. Few of the branches and ledges can support Yohko’s frame, and the serpentine paths can force you to retread the same ground to advance through the stage. Even if they don’t outright deny any feeling of accomplishment, the levels still expend a lot of energy delaying it.

Fear and uncertainty come to dominate the game. Playing Mamono Hunter Yohko feels like navigating an alien world that’s hostile to your every move. Some of its best moments play off this, in a macabre sense. Watching Yohko sink underwater or take a leap of faith into the unknown feel like a betrayal on the game’s part, like it’s ripped away what little safety you have with no guarantee that it will ever return it to you. In showing just how little it cares about you, the game makes your vulnerability all that more painful to bear. The game is generous with both checkpoints and continues, which alleviates some of the issues, though it’ll hardly be enough to see yourself to the end without becoming an expert at it.

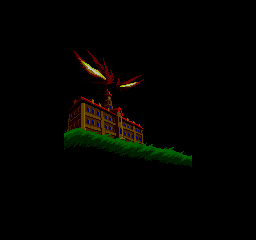

You’ve fought tooth and nail to survive every challenge the game has thrown at you. You’re beaten and battered. By the time you reach the end of the level, both your dwindling health bar and the clock above it signal just how little time you have left in this world. After all this, how does the game conclude your arduous journey? With the kind of clock tower bells one would hear at a funeral, presumably the ones mentioned in the title.

In fact, judging by the lack of ways to make Yohko more powerful (or even to effectively exercise what little power she has), it’s clear how interested the game is in vulnerability as an aesthetic. The shield demonstrates this well enough. While its defensive capabilities shouldn’t be neglected, it’s the shield’s offensive qualities that make it so useful. For one thing, it encourages indirect methods of attack where contemporary games encourage something more immediate and satisfying.

But the shield carries the same betrayal that defines the levels. By presenting it as a ranged attack, the game forces you into an ambivalent relationship with it. Your most effective form of offense only works by making you completely vulnerable to enemy attack. And because it’s your primary way of interacting with the world, playing Mamono Hunter Yohko becomes that much more unsettling. True, the shield returns to her a second or two later, but it still causes a brief moment of panic.

Of course, the game is still quite flawed. It takes a little bit to find its footing, and the occasional guide arrow undercuts the designers’ intentions of open-ended levels. Still, Mamono Hunter Yohko accomplishes something that few other games do. It’s the sort of game where the developers had an idea of what makes for a decent side-scrolling game, and didn’t quite know how to implement it, but still ended up creating an experience that manages to be enjoyable in spite of its extreme roughness.