An “iconoclast” is someone who fights against strongly held believes institutions, and it’s a powerful title for a game where its heroes stand up against an authoritarian theocracy. It is, outwardly, a cheery title from Joakim “Konjak” Sandberg, previously known for Noitu Love and freeware projects like The Legend of Princess, as well as being a sprite artist on several projects with Wayforward, like the Shantae series. But beneath its cutesy heroine and bubbly exterior lies a story about faith, and those misguided by it, all wrapped in a Metroidvania-type action game.

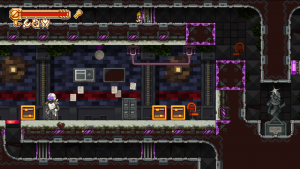

The star of the game is Robin, a silent heroine and a mechanic who’s quite handy with her gigantic wrench. Unfortunately, her skills run counter to the rule of One Concern, an organization that not only governs the planet, but also claims ownership of pretty much everything, ranging from property to its citizens’ chosen careers. It’s controlled by a religious figure known as Mother, who sits atop her throne in the headquarters of City One, and her minions follow her with zealous fervor. They are mining the planet for a precious resource called Ivory, a process which is not only pitting them against the heathen non-believers, but also ruining the planet.

The official mechanics of One Concern pay little attention to the otherwise boring town known as Settlement 17, so Robin takes it upon herself to fix things for them. This naturally attracts the all-seeing eye of their government to her attention, leading to her eventual imprisonment. She’s not in her cell long until she’s broken out by a women named Mina, herself part of the Isi Tribe that resists One Concern’s rule. Her subsequent escape leads her to be a wanted criminal and sets them up on an adventure to take down the evil government, as well as solve the mystery of the earthquakes which seem to be throwing the world in disarray. Their adventures taken them to Mina’s hometown, itself an underwater city built like a submarine, before infiltrating the One Concern’s central tower, and then finally into City One itself.

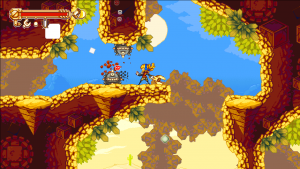

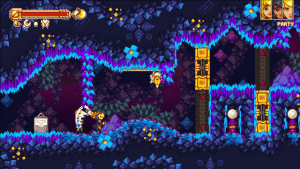

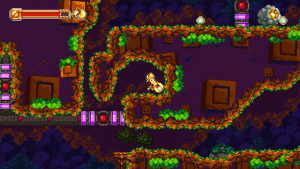

Sandberg points to Metroid Fusion as one of his inspirations for Iconoclasts, which can be felt in the way it’s structured. Each area is self-contained and the story itself is mostly linear, but you do get weapon upgrades that allow you to access new areas, and can revisit previously explored areas to find extra stuff. But as far as exploration goes, it’s fairly well focused, presented as something optional rather than mandatory. The other main influence is Monster World IV, which can be seen primarily with its adorable female protagonist, as well as the emphasis on meshing action and platforming with simple puzzles. Much like Westone’s Mega Drive classic involved creative uses for the heroine’s Pepelogoo pet, Robin uses her wrench and various weapons to trigger switches and unlock doors. While that aspect was somewhat limited in Monster World IV, it’s much more fully fleshed out here, as you obtain new upgrades and additional weapons with different properties.

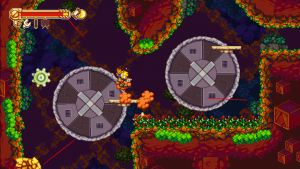

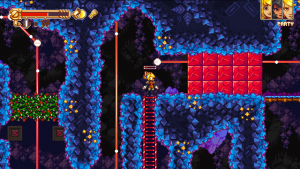

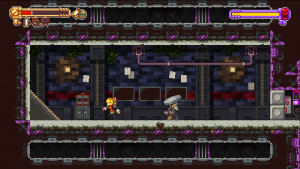

At the beginning, Robin just has a simple stun gun (it still makes non-human enemies explode quite fancifully), though she quickly obtains her signature gigantic wrench, which can be used to latch onto bolts and deflect certain enemy projectiles. As she progresses, she can find a bomb launcher, then an ability to spin her wrench to electrify herself, which powers certain types of switches, then the ability to imbue grenades with the same effect. The final weapon allows Robin to switch places with most enemies and objects. As it turns out, box puzzles are a lot more fun when you’re zapping them around the screen instead of pushing or throwing them (which you can still do). None of the puzzles are particularly difficult (and the ones that might require a little bit of thinking are usually optional), but they’re consistently clever throughout and never feel like filler.

Additional power-ups come in the forms of Tweaks, which are discovered on floating pieces of paper but created from various types of items you find in treasure chests. These are fairly minor improvements, like letting you absorb a single hit (since there’s no other way to expand your life meter), walk faster, or breathe underwater for longer. A few of these are fairly well hidden too, either in secret areas or as subquests presented by the games’ many NPCs. However, other than a dodge roll maneuver, none of these are all that significant, and it feels a little underwhelming to spend time searching for things that are just parts of items instead of anything that can be put to concrete and immediate use, like the health upgrades or weapon improvements/expansions. Still, the puzzles themselves are often satisfying in and of themselves, and it keeps the game from getting too unbalanced, keeping a strict focus on arcade action.

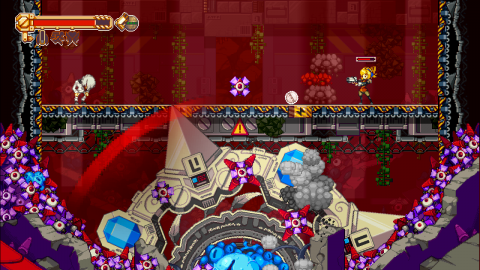

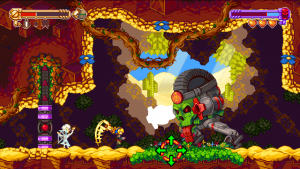

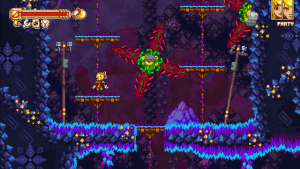

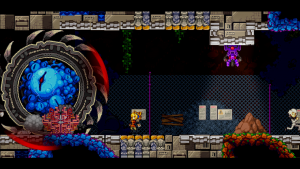

The puzzle philosophy can also be applied to the boss fights, which is a major area where Sandberg carried forward his expertise from designing Noitu Love. These challenge you to take some of the unique properties of the weapons while under pressure, putting both your creativity and reflexes to the test. This is also where the spritework is the most impressive, especially as you hit some of the screen filling bosses near the end of the game. For the most part, these are all well designed encounters, though there are a few cases where it’s not entirely clear what you’re supposed to do, and all you can do is absorb damage until you figure it out; though once you do, it’s usually not hard at all. There are a few minor sticking points regarding the controls – you sometimes need to use your wrench to deflect things, but since it has a split second wind-up, it takes awhile to get the timing down (especially in conjunction to the green flashes that enemies show off before delivering a counterable attack), plus you can’t duck and use your wrench, which may result in taking hits when you forget to stand up under pressure. Even with these issues, the penalty for death is light, as you can just restart the boss fight (though some have multiple forms, and it depends which you respawn at).

A few boss encounters have you working together with one of the other good guys, either in controlling Robin as they work to attack on their own accord, or switching between them to deliver attacks from different sides. This points to a rather unusual aspect of the game – through the entire adventure, there’s a “Party” status indicator which shows the other characters tagging along with Robin. However, this is only for story purposes, and you can’t actually switch between them; you can only even play as secondary characters for a couple of short segments. Considering the diverse cast and their own unique abilities, it would’ve been fun to play as them whenever you wanted to, but perhaps that would’ve opened up the scope far beyond what Sandberg intended, especially since the game was in development (solely by him) for nearly a decade.

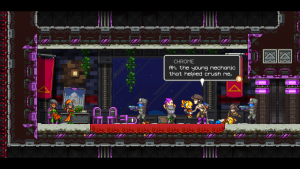

This does highlight how important the characters are to the Iconoclasts experience. While Robin and her friends (the pirate Mina, her brother Elso) are directly opposed to One Concern, more often than not, the antagonists are part of that same organization but pose a far greater threat to each other than Robin’s crew does. One of the core members of the team, Royal, is technically something of a chosen one, the hero who would succeed Mother’s throne when she passes. This would normally position him as an enemy, but he takes to Robin almost immediately after she saves his life, and believes he holds enough sway over the organization to get them to stop fighting. The fact that he doesn’t, as he slowly realizes over the course of the game, is a crucial part of his arc, which shows an incredible amount of development for someone who isn’t even playable. The same goes for Agent Black, a perpetually frustrated underling, and her commander, Chrome, who fashions himself as something of a cowboy preacher. You fight both of them, but they have such different interpretations of what is right, driven by either their emotions or by faith, that they become tragic figures in their own way. With these, the meaning of the title becomes clear, as the heroes fight against religion, or rather, the forces that would use to it to manipulate others for their own ends, as well as dealing with the unknowable nature of God.

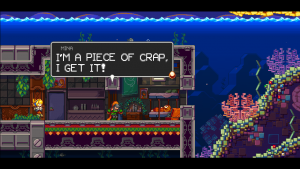

However, much of this is difficult to understand in the opening segments of the initial playthrough. The introduction establishes almost nothing of the setting, leaving all worldbuilding to occur through dialogue and (occasionally) from notes and computers. The mood also switches quickly switches between dark and serious to light and goofy at many beats, as is especially the case with Mina’s many jokey quips. The dialogue can be heavily stylized and many characters have unique ways of talking, but some of the writing comes off as a little awkward. The storytelling happens clumsily because there are all of these characters, as well as complicated relationships to both each other and their cultures. You’re just sorta tossed into the middle of things, and it’s all rather difficult to understand, as concepts are implied but only vaguely explained. But once everything clicks together, then its depths become evident, presenting a far more realized and nuanced world and featuring characters with more emotional depth than most RPGs. This is especially impressive for a Metroidvanias, which often struggle with telling any type of affecting story at all.

Beyond its structure and story, Iconoclasts simply “feels” right. This goes beyond the controls, which, despite the aforementioned quirks, are fluid and responsive. Everything from the detailed animations to the sound effects coalesces into an experience where it’s just fun to run around, grab onto platforms, and shoot stuff. It’s filled with details, like the Toaplan-esque skulls on the explosions after defeating an enemy, or the way the life bar slowly bounces when low on health, a clever replacement for the ever-hated beeping. Small maneuvers like latching onto screws and twisting them – something you do a lot in this game – are consistently fun just in their existence, thanks to the cute animations (notice the small beads of sweat flying off Robin) and the comical sound effects. Even the save statues are different depending on which faction’s territory you’re on, a small indicator of their different cultures. The ending credit roll lists a wide number of unique NPCs, showing the depth placed into crafting this story.

Beyond the retro games that Sandberg points to its influences, Iconoclasts recalls another indie classic – Cave Story. They’re both games that take place in unique worlds, filled with strange characters; they’re both open-ended experiences that focus primarily on challenge and level design over exploration; and they both revel in the sheer joy of running around and blowing up enemies. And yet, thanks to its setting, unforgettable characters, and fun puzzle solving mechanics, it stands out perfectly on its own, especially among an increasing crowded subgenre.

Iconoclasts actually began as a project titled Ivory Springs, which was released as a small freeware game back in 2009. Even back then, many of the basic elements were in place, down to the setting, main characters, basic level design, and mechanics. The characters are smaller and more super deformed, closer to the style of Noitu Love 2. This prototype has a few elements that didn’t make it into the final game though – it features items that boost stats rather than the Tweaks, and dialogue has character portraits next to them, where the final game lets the animation of the sprites speak for themselves. It’s interesting to play for comparisons sake, just so you can appreciate all of the little details that make Iconoclasts look and feel so much smoother and fun to control.

Links:

http://www.konjak.org/

Trailer With unique animation