- Sunless Sea

- House of Many Doors, A

- Sunless Skies

Welcome to the House. You are not welcome.

Released two years after Sunless Sea and developed as a part of Failbetter incubation program, A House of Many Doors might at first glance look like an unimaginative clone: it has trains instead of ships and an alternate universe instead of hollow Earth but it both looks and plays in a very simlar way: there’s top-down exploration, resource management with fuel and sanity, hull integrity meter serving as a lifebar and text-based cities in which the probability of success depends on your stats (affected by and increased with the help of your crew members). Even the writing style’s similar. Fortunately, there’s more to this game than just blindly following Failbetter and while it’s undoubtedly similar to and inspired by Sunless Sea, it might be an example of a student becoming better than the teacher.

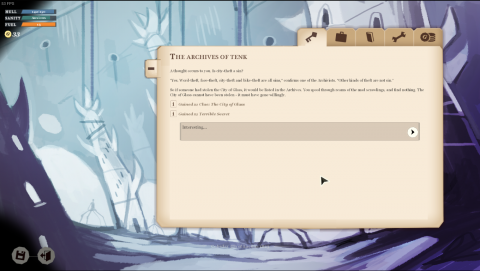

Gameplay differences between Sunless Sea and A House of Many Doors are mostly small tweaks: strategically turning the light on and off is nerfed because there are more downsides to travelling without the light (in a form of events with negative consequences) and turning it on takes time. There is no need to manage your food, with only the fuel and sanity being important. Experience points are called ‘apprehensions’ (‘fragments’ in Sunless Sea) , they’re easier to get and you spend them directly on increasing your stats (there’s no equivalent of ‘secrets’). Most of those changes (with an exception of actually needing to hold down W to move the train, as opposed to it moving automatically, which is fairly pointless and will probably hurt your finger) simplify the game but in a good way – they don’t dumb down, just reduce the tedium.

In addition to samller changes, there are three major ones. The most obvious one is that the combat is turn-based, not unlike in FTL: you move your crew around, repair the damage, target different parts of enemy vehicles with your guns, move closer to board them and move away to escape. It’s more fun than in Sunless Sea but similarly unbalanced: you’ll run away from everything in the beginning and steamroll through opposition near the end. The most important one is the lack of permadeath – it’s probably a good decision as, just like the title that inspired it, it’s heavily narrative-driven and the narrative doesn’t change that much in the early game, but it also removes much of the tension that could be felt when trying to return to a safe place while on the verge of death. The worst change is how the overworld works: it’s now divided into separate rooms with exits and entrances as well as randomized contents inside of them. The problem is that rooms within a general area feel repetitive and samey, making exploration boring and navigation by sight nearly impossible – you always need the map.

Like all the Fallen London games by Failbetter, A House of Many Doors focuses a lot on setting and atmosphere, although it mostly ignores the horror elements in favor of just being creative and weird. Some Lovecraft influence is still there, but the major literary influence here is Invisible Cities (which is also present in Fallen London and Sunless Sea, although not quite as pronounced). At its heart, the game is all about strange, high-concept locations and societies that develop in them: a moving cathedral inhabited by pirates who steal gods, a violent and chaotic circus-kingdom, a realm of insects on the verge of slavery-related civil war and many others. All of those places are a part of the House: an ever-changing world which steals parts of the other world and imprisons anyone who happens to be in those parts.

There’s also the game’s story – your character’s quest to escape from the House. Like in many games of that type, it’s mostly an excuse to travel around the setting and take part in as many interesting side-stories as possible. Unlike in most games, care was taken to integrate those elements: escaping the House requires understanding the House and its history, and the voices that guide you in your dreams will make sure you stumble upon as many fragments of a larger picture as possible. While the main storyline predictably takes a backseat, it’s actually pretty good and has a few interesting surprises along the way.

In addition to the setting and the plot, the game also adds many small, seemingly irrelevant touches that end up adding a lot to its style and personality. Perhaps the most interesting ones are the activities that are available in City of Keys, the game’s equivalent of London in Sunless Sea: your character can donate items collected in his journeys to a museum, which can then end up as either an invaluable source of historical knowledge, a collection of mysterious items with occult powers or a beautiful art exhibition. You can also become a writer by submitting articles to different newspapers, getting your books published, working on a perpetually unfinished magnum opus or writing poetry (which is one of your main sources of experience, and also gives you a short, procedurally-generated poem).

One place where A House of Many Doors differs from Sunless Sea is when it comes to characters. Members of your crew are much more fleshed-out now, and they actually feel like real people (it might have something to do with them having real names, although it’s not as important as the fact that there’s more writing devoted to them). Most of them have a fairly lengthy story arc with a few possible endings – the game even has Fallout-like ending sequence describing what happened to them after the events of the main story. The increased character focus is one of the best ideas when it comes to the narrative of A House of Many Doors: building relationships with your crew makes the whole game much more emotionally engaging.

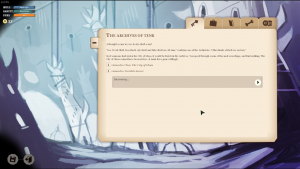

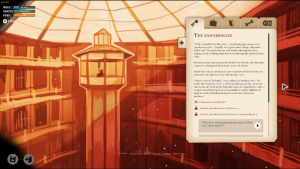

The game’s graphics have been created by Catherine Unger (also known for her work on Detective Grimoire). While during the exploration they don’t seem too impressive (probably due to how all the randomized areas blend together), they really shine when the game displays a full-sized static image during the text-based sections. The pictures have a watercolor-like quality to them and they’re full of unusual angles, flowing lines (especially in the dream sequences), blurred backgrounds and amazing use of colour and lighting. The soundtrack, composed by Zach Beever, goes really well with those pictures while also adding tension to the exploration parts (which is one of the few things that keep them from making players fall asleep). The best pieces of music have to be ‘Glimmers and Dust’ with its melancholic vocals, guitar strumming and reverberating drums, followed by the fast-paced, piano-focused combat themes ‘Oh No! Everything’s Exploding!’ and ‘Shrapnel Sonata’. Unfortunately, the game doesn’t inherit Sunless Sea’s habit of gradually increasing and decreasing the music’s volume as you approach different cities, which would make exploration more bearable.

In the end, A House of Many Doors is a Sunless Sea clone done right: it understands that game’s strengths and weaknesses and manages to use them to improve on it while remaining original and interesting. It’s slow but not boring, it’s mysterious but it never feels unfinished and it’s surprisingly full of new ideas (although more for story than gameplay). It’s not without its flaws (e.g. it seems that the author like Sunless Sea’s Frostfound quest so much that he made you do it at least five times here) and rough edges (although most of the big bugs have been fixed after the launch) but there’s too much creativity in it for it to be dismissed as just an attempt to follow in Failbetter’s footsteps.