It’s no surprise that Heroland (released as “WORKxWORK” in Japan in 2018) was completely overlooked around its release in December of 2019, a time when everyone was eager to see what 2020 would bring. Heroland isn’t a game that will convert JRPG naysayers, but those with the patience to persevere will be rewarded with a genuinely funny, sharply written game that isn’t afraid to wear its politics on its sleeve.

Heroland was developed in part by FuRyu, a company responsible for innovative JRPGs that uses proven talent to head essential parts of their games. For example, The Alliance Alive had Yoshitaka Murayama (Suikoden) as its lead writer. Heroland follows in these same footsteps, employing Nobuyuki Inoue (director of Mother 3) for its writing and Tsukasa Masuko (Shin Megami Tensei) to compose the soundtrack. Netchubiyori Limited, whose previous work mostly includes PSP games based on licensed anime, was also involved with the game’s development. Xseed Games is responsible for the title’s localization, and they did a fantastic job; Heroland is bursting with referential humor and informal language that could have easily been a localization nightmare, but Xseed has ensured the humor and wit shines throughout the experience.

As Lucky, a newly hired tour guide for Heroland, the resort island where customers live out battles experienced by legendary heroes, your job is to ensure your clientele have the best experience possible by guiding them through various dungeon tours. Heroland is quickly established as an example of late-stage capitalism in motion – employees are expected to work unreasonable hours for minimal pay, live in inadequate conditions with bathrooms that cost money, and eventually take part in surgery that permanently turns them into a mascot. When Lucky and his fairy companion Lua get wrapped up in Heroland’s nefarious scheme by breaking a vase worth one billion $tarfish (the game’s currency), they have no choice but to discover the resort’s darkest secrets in order to find a way out of their predicament.

Characters

Lucky

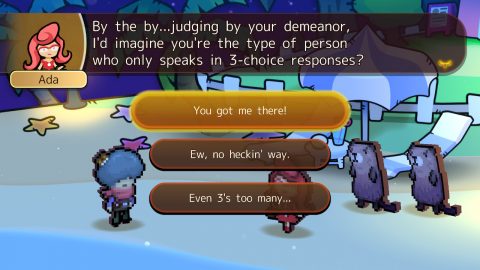

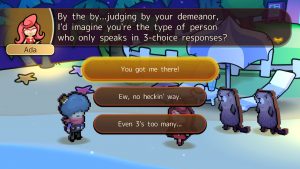

The protagonist of Heroland who can only speak in three-choice responses. He applied to work at Heroland in order to support his family, not knowing the trouble that would soon follow.

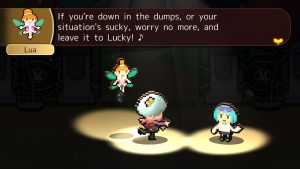

Lua

An “exposition fairy” who does all the talking for Lucky. She’s very hotheaded and tends to bicker with the customers. She’s not just here to help Lucky, however, as she has her own goals in mind…

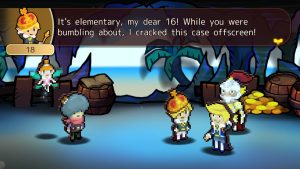

Prince Elric / “18”

A prince from the Knowble Kingdom and 18th in line to the throne (hence his nickname of “18”). He comes to Heroland in order to slay the Dark Lord, which he thinks will make him next in line to the throne. For much of the game he’s a cocky brat, but he changes greatly as he bonds with Lucky and certain events make him question his beliefs.

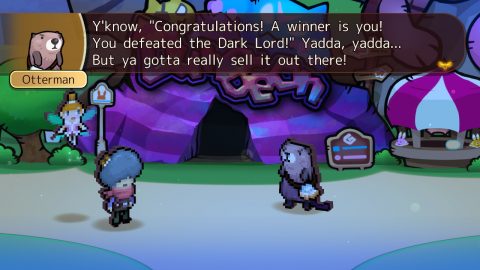

Otterman

A fellow employee of Heroland who insists he is 100% human despite his appearance. He lends a helping hand to Lucky throughout the game in combat and via lore dumps whenever you make it to a new dungeon. Also runs a black market business on the side as “S. Muggler”.

Ada

As secretary to the president of Heroland, Ada runs Heroland with an iron fist in his name. She enforces the resort’s insane policies, organizes the schemes that put employees into eternal debt, and frequently requests the impossible from Lucky. She’s essentially the antagonist until Derk Lorde starts getting directly involved.

Derk Lorde

The intimidating president of Heroland and the Dark Lord who fought the legendary heroes in the past. He claims to be a changed man since his defeat and just wants to run Heroland in peace, but it’s an obvious cover for his true intentions – to obtain the Demon’s Pearl and use it to gain ultimate power.

The main story is actually where the writing of Heroland is at its weakest. The pacing of many cutscenes is dragged down by Lua, who has an annoying tendency to react incredulously to almost everything other characters say. It doesn’t pick up or even have a clear-cut objective until more than halfway through, where multiple parties of great import start showing up at Heroland. From there, the plot simply becomes a MacGuffin hunt in which the twists are obvious and multiple events are mentioned without being shown. Even the ending is played as a joke, so players who plan on rushing through Heroland won’t get much out of it. Where Heroland shines though is everywhere in between – its unrelenting comedy channels the spirit of a Working Designs localization and Nippon Ichi Software’s Disgaea series to provide a memorable journey.

Humor in Heroland relies on repeated gags, pop culture references, and a heavy dose of memes. During dungeons and cutscenes, characters will take the time to crack jokes, reference things that are chronologically impossible (the game takes place during the 14th century, yet things like Final Fantasy and Keanu Reeves’s appearance at E3 2019 are referenced), and have bizarre conversations like debating the best way to drink milk. Even NPCs get their time to shine, with the funniest example being an otter who’s convinced he’s the protagonist of an Isekai anime after getting hit by a truck that somehow transported him from Voorhees, New Jersey to Heroland.

But Heroland does occasionally get serious, with one such example being a chapter that takes a bit of time to talk about the harsh reality of the manga industry – excessive work hours, lack of unionization, and working for “exposure”. The customers of Heroland have some very real problems, too. For example, during the sidequests for Linda, a seemingly ordinary mother of two, she contemplates the darkest moments of her marriage, such as fights with her husband or her postpartum depression that caused her to leave her family for two years. Even the more fantastical characters like the brooding knight captain Cee Plusse have relatable problems, as his sidequests are all about helping him obtain toys and other things he missed out on due to his rough childhood. It’s captivating stuff that incentivizes getting to know the characters well enough to unlock and complete their sidequests. The only problem is that increasing your bond with your customers involves lots of combat, which is unquestionably Heroland’s biggest flaw.

Characters are assigned one of five roles (Warrior, Mage, Tank, Healer, and Freelancer) and the skills available to them are determined by weapon they wield and their exclusive skill known as a “Chara Skill”. The major limitation here is that each weapon only has one skill and each character only gets one Chara Skill, so a character will never have more than three options (one being a standard attack) for the entirety of the game. The roles are poorly balanced as well, with Warriors and Mages being the most effective by far.

Dungeons are laid out in a sequence of tiles, much like a board game. Your goal is to move from left to right, defeating enemies along the way, until you make it to the boss that waits at the end. Sometimes you’ll get branching paths that determine which enemy groups you fight, but beyond that, every dungeon is identical. Thankfully, every dungeon has at least a few cutscenes to break up the monotony, as well as other events like a black market dealer you can buy rare furniture from or a chance to repair your weapons courtesy of the blacksmith.

As the tour guide for your dungeon party of four, your job is to watch your party fight automatically, intervening to help as necessary. Gauges will start filling, and as they fill, combatants will decide what to do. Basic attacks occur as soon as the gauge fills, but skills have casting time before they trigger. In addition to using items, you can either give general party-wide commands or you can give specific guidance to a single character. It’s essential to intervene with commands, as the AI tends to waste skills on weakened foes or try to heal allies who are barely hurt. After doing something, Lucky will have to wait a bit before he can assist again, a penalty that gets reduced as Lucky’s guide level increases. The biggest flaw with the combat is that it’s incredibly slow, making even the simplest of battles take several minutes. The saving grace is that there’s an option for speeding up battles available at any time, but it just feels like a cheap solution for an otherwise huge problem.

While there’s a nice variety of foes, between things like slugs, trolls, and giant gumball machines, they all get palette swapped several times and even bosses get excessively reused during sidequests. Bosses aren’t any better to fight than regular enemies either, as none of them ever incorporate any tricks to change fights. What you do during hour one feels exactly the same as what you’re doing during hour 30, and it makes the game a total slog to play.

As you win battles, enemies drop treasure for you to pick up that you can either give to your customers to increase their satisfaction level or keep for yourself to decorate your room with later. Sometimes you’ll get a weapon replica or rare plushie, which unlocks a new weapon or monster summoning capsule respectively if Lucky keeps it. Customer satisfaction is something that can be earned through battle when allies score KOs or land critical hits, too. At the end of a tour, the satisfaction and earned experience of your party is tallied up, which affects how much guide experience Lucky gets. Weapons also have a chance of breaking at the end of a tour based on how many skills you used – it’s not a particularly common occurrence, but it feels like a pointless mechanic meant to waste your $tarfish.

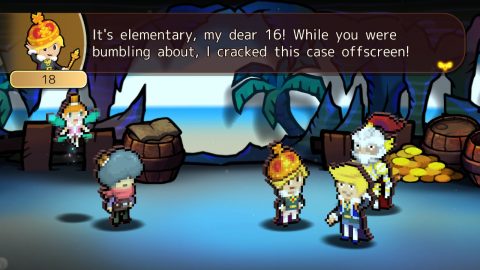

Heroland uses a very interesting visual style that takes 2D sprites and puts them on 3D models to create characters that still look like 2D sprites, but can also bend, stretch, and grow like 3D models. It’s a look that’s reminiscent of games like Paper Mario or Parappa the Rapper with how the characters waddle when they move or rotate before changing expressions. All of the characters are charmingly diverse and have unique animations in battle that add some personality, such as the way Philip the dog holds weapons in his mouth or how Mana, one of Elric’s fangirls, puts on her glasses whenever she casts magic. Dungeons don’t hold up well in comparison, since they all use static, unimpressive backgrounds and there’s only nine of them, resulting in the player seeing the same dungeons with the same backgrounds dozens of times.

The soundtrack of Heroland effectively matches the environments it’s used in – the music that plays on the bright Heroland map sounds appropriately tropical and idyllic, for example. Another highlight is the melancholic theme played in Lucky’s depressing room. The battle themes are rather good as well, with the standard one sounding like something you’d hear in a circus and the boss theme using guitar riffs to create a fittingly intense and moving sound. The boss theme even changes into a slower, more dramatic version once you get far enough into the game, which is a cool touch. There’s no voice acting in Heroland, but gibberish sound effects are used instead, similar to Banjo-Kazooie. It’s a fine idea on paper, but they tend to be pretty shrill and grating.

In the end, the appeal of Heroland is similar to cult classics like Nier or Deadly Premonition – it’s a game that’s extremely tedious to play, but rewards the few who can make it through with exceptionally clever and heartfelt writing. While the game will likely never catch on the way those two games did, perhaps there’s some hope JRPG fans looking for something different will eventually take notice. With enough interest and a higher budget, a sequel could do wonders and turn an interesting but flawed game into something truly special.

Links

https://legendsoflocalization.com/locxloc-behind-the-screens-with-herolands-localizers/ – Great article discussing the localization process for the game