“All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.”

– Edgar Allan Poe

Considered by many to be one of the first great American writers, Edgar Allan Poe created stories that have chilled readers for two hundred years. His life was a short and difficult one, full of pain and tragedy, yet he managed to leave behind a collection of stories that will be remembered forever. In 1995, inScape – publishers of The Drowned God, Devo Presents: Adventures of the Smart Patrol, and The Residents’ Bad Day on the Midway – used Poe’s stories as the starting point for a unique, original adventure game experience: The Dark Eye. Spear-headed by Russel Lees, whose more recent work includes Full Spectrum Warrior for Pandemic Studios, and featuring the talents of Thomas Dolby and William S. Burroughs, The Dark Eye still manages to leave the player with a disquieting sense of unease.

– The Dark Eye, opening narration

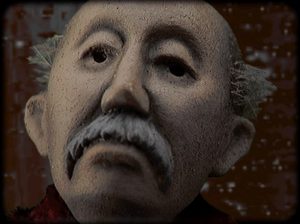

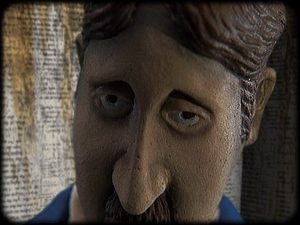

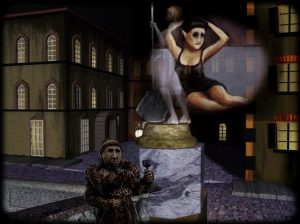

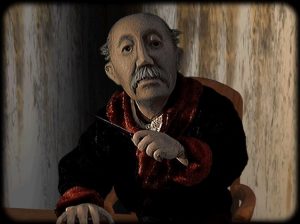

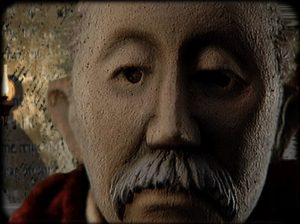

In the opening of The Dark Eye, your player character is a nameless man, lacking any distinguishing features even in a clear reflection. You arrive at a large house, where you are thrust into the story. The primary storyline in the game (called “Malevolence,” according to an interview), which is very loosely based on Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. It serves as a framing story for the rest of the game. The dialogue, characters, and plot are an exceptional recreation of Poe’s style. As the game progresses, your characters becomes caught up in the tragic story involving his uncle (perfectly voiced by William S. Burroughs), brother, and cousin. The uncle’s servant is the first character you see in the game, and his odd appearance is an excellent introduction to the graphics of The Dark Eye.

In the opening of The Dark Eye, your player character is a nameless man, lacking any distinguishing features even in a clear reflection. You arrive at a large house, where you are thrust into the story. The primary storyline in the game (called “Malevolence,” according to an interview), which is very loosely based on Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher. It serves as a framing story for the rest of the game. The dialogue, characters, and plot are an exceptional recreation of Poe’s style. As the game progresses, your characters becomes caught up in the tragic story involving his uncle (perfectly voiced by William S. Burroughs), brother, and cousin. The uncle’s servant is the first character you see in the game, and his odd appearance is an excellent introduction to the graphics of The Dark Eye.

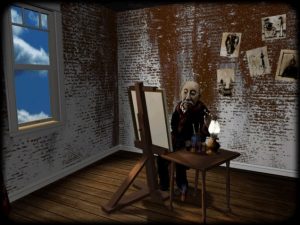

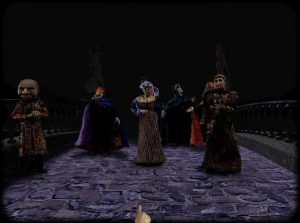

All characters in the game are portrayed by puppets, as in a stop-motion animated film. These puppets are one of the defining characteristics of the game, and they are absolutely first rate. The faces are distorted, gray caricatures, their unifying trait being the lack of any eyes – most characters have shadowy, empty sockets. This gives the unsettling impression that they are staring at you at all times. These character images are generally seen as a series of still pictures, although there are numerous videos where they are convincingly animated.

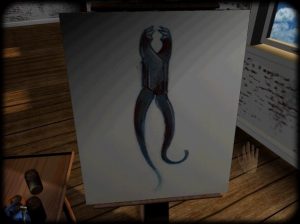

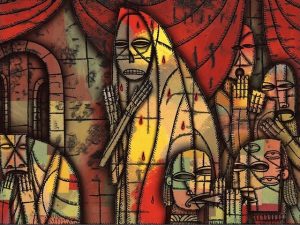

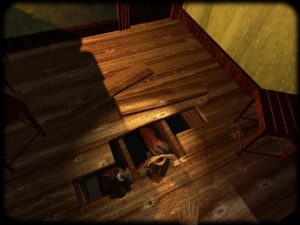

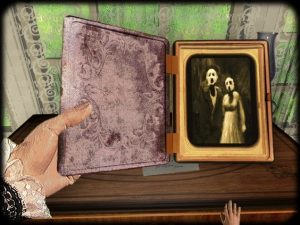

The Dark Eye does feature art other than the puppets. The game is littered with paintings, video montages and more in a variety of styles and mediums. All of it is first rate and adds to the atmosphere of anxious unease. The backgrounds, unfortunately, do not hold up nearly as well. They will look familiar to anyone who has played adventure games from the time period of Myst – they are adequate, but strangely shiny. These settings lack realism, especially compared to the amazing puppets populating them. The contrast is not exactly jarring, but one can’t help but wonder how much better it would have looked if they had built actual sets to better suit the puppets.

The gameplay is that of a stripped down point-and-click adventure: you point and you click. You have no inventory, although you will occasionally pick up and use an item such as a sharp or blunt instrument. There are not any true puzzles to speak of, aside from trying to guess what comes next in the story. This might be a turn off to gamers seeking an intellectual challenge, but for those who are simply hoping for a new experience, this will fit the bill. Your default cursor is a translucent human hand, and if you are able to move or interact with something or someone in the game, it wiggles and shows what can be done with various hand signals. One interesting action is a cupped hand that is moved back and forth across an object – this triggers various memories or thoughts.

The Malevolence portion of the game functions as a framing story, like the storytelling bride of One Thousand and One Nights or the inn from Neil Gaiman’s Sandman: World’s End. You explore the dilapidated house and speak with your family members. As the main plot progresses, the scene will shift and the house will become dreamlike, as if your character has entered into a trance. The other characters disappear, and voices begin to whisper in the background. At this point, you seek out your reflection in objects around the house. Finding these items triggers a new story to begin.

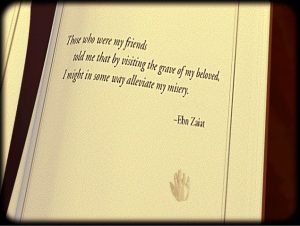

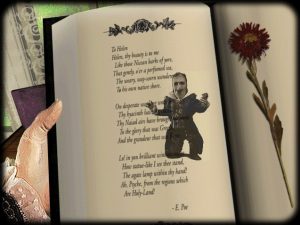

During the course of the game, you directly experience five of Poe’s works: “Annabel Lee,” “Berenice,” “The Cask of Amontillado,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Two of the sordid tales are read to you, accompanied by an artistic slide show, while you actively play through the other three. You trigger the transition to these stories inside the trances, and the effect is intentionally bizarre, as if dropping in and out of dreams. The playable sequences are faithful adaptations of the original stories. They all involve a murder, and you play through them each twice: once as the murderer and once as the victim. The use of multiple perspectives is an ideal way to add interaction to what are fairly scripted plots. The feel of the game shifts dramatically as you switch between playing a naive, haunted individual to taking on the role of a killer gripped by madness. For players familiar with these stories, there will be no surprises, but the twists and turns could be a treat for the uninitiated.

Scattered among these scenarios are opportunities to do what the manual refers to as “soul jumping”. This gives you the opportunity to switch from the murderer to the victim or vice versa by clicking on their eyes when they show your flickering reflection. This was lifted from an earlier iNSCAPE game, Bad Day on the Midway, and the designer said in an interview that he regrets its inclusion. It interrupts the story without adding to it, and at times can be quite frustrating. I once found accidentally myself as the murderer a second time, after I had just finished putting someone in the ground. The two stories are that watched and listened to rather than played are still enjoyable, and feel more like bonus content than a short cut. One of the stories, read by Burroughs, is illustrated with what looks to be Picasso-inspired artwork. The other is paired with various mixed-media images, reminiscent of Dave McKean’s work.

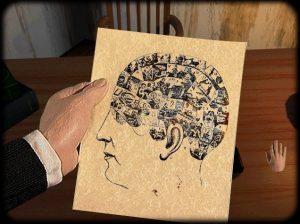

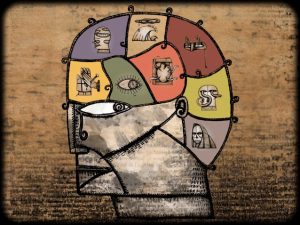

While only five stories were actually included, there are many allusions to other Poe stories. Whether it be a painting or a stray newspaper article, one never forgets the original source of the game’s terror. As you complete the various story levels, you have the option to replay them using the Phrenological Map menu, which serves as a level select throughout the course of the game. Phrenology, later discredited, was a popular method of psychology that involved examine the shape and size of the human skull. The map starts out blank, but is slowly filled in by stylistic icons of the various narratives inside the game. This allows you to replay completed level and also serves as the load screen; your game is automatically saved as you play, and you can resume from either the main story or an uncompleted side story.

The game’s audio adds much to the game’s shady experience. All of the characters’ voice acting is quite well done and brings each scene great depth and personality. The cast is excellent, especially for its time, and while not every voice is spectacular, certainly none would be considered dead weight. Another excellent use of voice are the fleeting, audible thoughts of the various player characters. These thoughts are often repeated, poignant phrases, sometimes accompanied by short video clips or other imagery. Their repetition is possibly the strongest way in which the game simulates madness. The game’s score was created by Thomas Dolby (“She Blinded Me With Science!”) and the company he founded, Headspace (now Beatnik). The music sets the mood perfectly, and it’s only unfortunate that the included pieces are not of longer composition. The tunes are both haunting and memorable.

The game is certainly not long, and could easily be finished in several evenings without a walkthrough. It feels complete, however, and it steadily ramps up to deliver a satisfying, nightmarish ending. There are, however, a few minor criticisms to be had. As mentioned, time has shown that the backgrounds during gameplay truly don’t fit with the rest of the game’s otherwise stellar art direction. The game’s replay value is also sadly lacking, as the only thing that could change is the order in which you play the various stories-within-a-story. And the soul jump is a truly inspired idea – if only it had been better utilized, allowing you to jump into the various minor characters into the game, just for a moment, to see things from their viewpoint. It would have been great to witness the story of “Berenice” from the maid’s perspective, or “The Tell-Tale Heart” through the eyes of the policemen.

The game’s biggest faults has to do with control and a lack of clear goals. Movement is not always clear; clicking on a right turn might turn you 90 degrees or 180 degrees. This makes it completely unintuitive to move about an area, especially the maze-like catacombs. As for a lack of goals, it would be understandable if it were only a matter of it being difficult to know what to do next, but there were several instances where playing the game amounted to guessing where to stand. One specific scene, the bridge scene from Fortunato’s perspective, extremely frustrating even though it’s pretty clear of what’s needed to do in order to continue.

Despite these shortcomings, this is a rare case of classic literature successfully being adapted into an interactive game. The short stories used are just as gripping as when Poe first wrote them and the makers of The Dark Eye does an expert job portraying them in a fresh, compelling fashion while keeping the spirit of the original works. The art design was truly amazing, and the inclusion of talent like William S. Burroughs was ingenious. One can hope that future game designers will find inspiration in The Dark Eye that will allow them to work the same magic.