The horror stylings of H.P. Lovecraft have had a massive influence on the horror genre at large. Countless works channel them, from video games like Alone in the Dark and children’s shows like Inhumanoids: The Evil That Lies Within to films like From Beyond and In the Mouth of Madness. Only his works from before 1923 are technically in the public domain, but even in life Lovecraft was encouraging of other creators borrowing from and referencing his work, coming to like the idea of his fictional mythology becoming more convincing if it grew more ubiquitous. While Lovecraft himself is long gone, his legacy remains, with “Lovecraftian” becoming a household word for people discussing the innumerable examples of fiction, film, board games, comics and video games that use his ideas.

The Consuming Shadow is one of the latest attempts to capture Lovecraft’s style of impending doom in video game form, and is very successful at it thanks to great writing and some clever use of randomized game elements. The game begins with an unnamed scholar realizing that the world is going to end in sixty hours. The reasons differ from game to game. The information could come to him in a dream, or be something he deduces from studying an ancient text or the alignment of the stars. Either way, our hero realizes that three non-understandable ancient entities have taken an interest in our world. As in many of Lovecraft’s texts, these would be interdimensional destroyers were once worshipped as gods on earth, but are in truth unquantifiable masses of shadow that transform their followers and those around them into hideous creatures. Realizing that time is short, the Scholar sets out from the Scottish border to explore England and Wales, hoping to find some answers and stop the Ancient’s invasion in time.

The Consuming Shadow makes good use of its randomized content regarding the game’s backstory. Rather than just having randomized rooms to explore and random enemy placement, information on the game’s three Ancients is randomized as well. The Scholar learns that one of the three wishes to encompass and obliterate our world, another one is helping it, and the third is uninterested in humanity, but is an enemy of the other Ancients. Their affinities, attributes and even their very names are randomized from a pool of possibilities with each new game. Fortunately, the game gives players a Clue-like spreadsheet and notebook to track which Ancient is associated with what emotion, color, and so on.

Randomizing this instead of just the game’s levels works as a fitting tribute to the type of horror Lovecraft would try to evoke. A hopelessness born not of a lack of knowledge of a thing, but rather a fractured knowledge of it, with some details intimately known as others are just beyond reach. Very few video games take this approach to their exposition, though those that do, like Bloodborne or Silent Hill 2, are often lauded for it. For The Consuming Shadow, the approach adds an extra layer to the game where victory is not achieved through physical combat but by skimming through recovered texts to deduce the incantation necessary to banish the invading Ancient from our world.

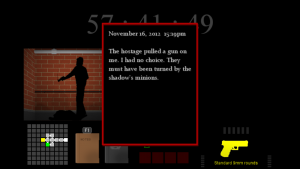

It’s also a good thing this extra aspect of the game is present. The levels are fun to creep through, but would quickly become boring without the urge to delve as deeply into them as possible to find as many bits of information as possible before fleeing. The actual combat is very simple. The Scholar can either shoot enemies or bludgeon them to death with his firearm. There are also magical spells that can be learned while exploring, though some sanity is lost each time they are used. There will also be a keyset that has to be found to access every room of each area. It is possible to pick locks, however, the chances of this working are relatively low, and it’s often better to find the actual keys anyway so as not to miss out on any other important items. It’s possible to exit a room instead of fighting its residents, but leaving a room without killing every monster in it first also reduces the sanity gauge. In spite of the game’s simpler single screen rooms, “insanity” is implemented in ways similar to those in Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem. As it decreases some monsters will turn out to be harmless hallucinations, doors will seem to shift around the room a bit, controller inputs will be reversed, and so on.

But there is also a truly unique use of the sanity gauge: The lower it gets, the more often the navigation buttons flicker and change from their normal destination to “Kill Myself.” Players who click at the wrong time are immediately treated to a short scene of suicide by gunshot. It’s possible to “change your mind” and continue exploring by rapidly clicking or button mashing, but this becomes more difficult in each successive instance.

Fortunately, while scenarios are randomized each time, the Scholar is not. Upon death, you receive points for everything you’ve accomplished. Your score carries over from game to game, granting access to special bonuses as it increases. You can also unlock three other characters as you progress.

The Warrior: A hapless enforcer thrown into a battle against minions of the Ancients. He has no firearm, but superior melee capabilities. Most importantly, however, with the right timing he can dodge to avoid enemy attacks. The Warrior seems underwhelming at first, but as he levels up players can begin each game investing more and more into his melee damage, making him the least stressful character to play as overall.

The Ministry Man: A David Duchovny to the Scholar’s Victor Wong, the Ministry Man’s more dapper style reflects his starting condition in the game. His mission begins near Stonehenge with most of the blanks already filled in. The nature of each town is already revealed, and he also has the banishment ritual figured out save for the name of the invading Ancient. He also starts with £100 instead of fifteen, letting him quickly buy up items without doing the same dirty work as the Scholar and the Warrior first. The downside is that he only gets twenty hours to deduce the Ancient’s name and perform the ritual before the world ends.

The Wizard: An extremely powerful character if used correctly. She has no weapon, but during her time as a captive of the Ancient’s minions she paid attention and learned every spell in the game instead of going insane like most other captives found throughout the game. Not only does she know every spell by default, she doesn’t lose sanity when casting them. Unfortunately she is the most convoluted character to unlock, requiring that the player has the right item, encounters the right variation of a particular random scenario, and successfully travels across the map while playing as one of the other characters.

As the game’s combat is very simple and the dungeon layouts are randomly generated, it falls upon The Consuming Shadow‘s atmosphere to keep players intrigued by the details of its otherworldly invasion. Fortunately, this aspect of the game is brilliantly executed. With a soundtrack and structure evocative of John Carpenter films like Prince of Darkness and In the Mouth of Madness, every part of The Consuming Shadow is dripping with a grim urgency that is impressive for a game where half the time playing it is spent looking at a map and a spreadsheet. The writing is very effective here, with every town described as being on the brink of falling apart at best, and having the player’s car be their base of operations helps stress the need to keep moving. To really drive the point home, a giant timer is shown at the top of the screen while exploring, and the hours also dramatically count down while driving (though for such desperate times, it seems strange that the car’s top speed is about 48Km/H).

The game’s locations are also excellently presented because you barely see them. All four characters are equipped with a weak flashlight, and rather than having detailed 3D models or colorful 2D sprites, every single character and enemy is presented only in silhouette. This is a great way to keep things moving and tense, as the large amount of darkness dictates that players explore a room quickly to “see” as much of it as possible, which puts the character at risk of bumbling into an unpleasant creature. The game’s enemies are all well designed, with a great assortment of painful sounding gurgling and groaning, which more than makes up for their lack of visual clarity. Each one is a type scene in various takes on Lovecraftian fiction, but presenting them as loud sihouettes forces the player to fill in the blanks. As an extra touch, there are verbose descriptions for each enemy type that are unlocked gradually by fighting them. These give some insight into their workings and also some useful information on their vulnerabilities.

The Consuming Shadow‘s levels also keep things desperate even after the player completes one. There are numerous objectives that can be chosen when investigating a given location, from rescuing prisoners, to finding specific pieces of information, to closing a rift from which unearthly lifeforms are emerging. No matter the motive, after completing a mission it is mandatory to also exit the building and make it back to the car. While the first instinct may be to explore every room fully for potential extra items and information, completing an objective will often stir more powerful forces. Dallying in an area once one’s business is completed carries the risk of being pursued by some of the game’s more ruthless enemies. The most interesting of these is the Overseer, a barely formed massive face that slowly encompasses a room. If it catches up to the character, he or she blacks out and then awakens in a random place, wasting a lot of time to get back on track.

This and the ubiquitous countdown are just a few of the ways time management becomes the most important aspect of the game. When driving from town to town, a large variety of random encounters will happen, which can also result in a change of location or even more wasted time, depending on your choices. They’re used to great effect, as they’re intriguing and feel worthy of pursuit in the early game. As the clock ticks down, however, it will be common to choose the “shrug and drive on” option while openly allowing innocent people to be taken by the game’s oncoming monsters. There’s no penalty for doing this, so it’s up to the player to weigh the potential rewards of getting out of the car rather than trying to reach their destination in time.

As the game goes on, the character is at increasing risk of suffering more serious mental and physical harm. Besides a loss of sanity, repeated damage from enemies and some encounters can result in extreme anxiety, bleeding and broken limbs, each with their own detrimental effects on the character’s performance throughout the game. Time permitting, these injuries can be cured by visiting a hospital in a friendly town. But in some cases it may be worth abandoning a besieged town to the shadows entirely depending on how well stocked the character is. Every decision in the game is a slight gamble that can have disastrous results further down the line.

Finally, the game demands further time management decisions in the friendly towns. Time is spent just to see what’s for sale. While extra ammunition is impressively cheap and ubiquitous for a game set outside of the US, there are also twelve items randomly scattered throughout the game world to buy or find. These offer invaluable bonuses, like preventing the player from suffering specific injuries or increasing the chances of finding certain items. The randomness is again key here, as it’s necessary to weigh finding something that might be useful against time that could be spent learning more information about the Ancient’s rituals and identity.

While many games are advertised around having “Rogue-like elements,” The Consuming Shadow embraces that genre’s trademarks not just for the sake of randomized levels or for a bloated number of items to find, but instead across every aspect of its design to help create a successfully Lovecraftian atmosphere. The game was created by Ben “Yahtzee” Croshaw, and while it’s not his first, it’s definitely his strongest yet. The levels can get repetitive, but the morose, John Carpenter styled soundtrack to the ultra-bleak writing makes The Consuming Shadow more than the sum of its parts. The Consuming Shadow is currently available for download both at The Humble Store as well as the Mac App Store. It’s worth playing not just for fans of “Rogue-like” games but by horror fans in general for its sinister, slow burn atmosphere.

Links:

The Consuming Shadow Official homepage.

(Ed Note: one of the producers for this title is a contributor to HG101’s Patreon. The author was not aware of this until after this review was completed and posted, so this did not factor into their opinion.)