- Command and Conquer

- Command and Conquer: Red Alert

- Command and Conquer: Tiberian Sun

- Command and Conquer: Renegade

- Command and Conquer: Red Alert 2

- Command and Conquer Generals

- Command and Conquer 3: Tiberium Wars

- Command and Conquer: Red Alert 3

- Command and Conquer 4: Tiberian Twilight

- Command & Conquer: Generals: Combat Cards

- Command & Conquer 3: Tiberium Wars (Mobile)

- Command & Conquer: Red Alert Mobile

- Command & Conquer: Red Alert (iOS)

- Command & Conquer 4: Tiberian Twilight (Mobile)

- Command & Conquer: Tiberium Alliances

- Red Alert OL

Since 1995, the Command and Conquer franchise has taken its place among the classics defining the real-time strategy genre. Originally developed by Westwood Studios, it’s left a continuing legacy that has outlasted its creators and survived an ignoble fall at the hands of Electronic Arts. Of the three continuities that have emerged over the years (including the Generals timeline), however, the spin-off Red Alert series stands out as being just as memorable as the original Tiberium universe.

Following the success of the original Command and Conquer – also known ever since by its working title, Tiberian Dawn – Westwood toyed with a variety of ideas on what to do next. The developers settled on going back in time, chronicling an alternate history that would eventually lead to the events of the Tiberium games. This idea evolved into Command and Conquer: Red Alert (or Red Alert), released on November 1996 and distributed by Virgin Interactive. While only the second entry in the franchise and sharing quite a few similarities, it’s sown the seeds of things to come.

The premise itself, for its time was rather unique for an RTS. In 1946, Albert Einstein creates an experimental “Chronosphere” machine, which he uses to travel back to 1924, finding a young Adolf Hitler just out of Landsberg Prison in Germany. Then with a fateful handshake, he erases the would-be Fuhrer from the timestream. But upon returning back to the “present,” he discovers too late that changing history has unintended and bloody consequences. For the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, now under an even more dangerous and aggressive Josef Stalin, has set its sights on Western Europe; without a Nazi Germany to keep Communism in check, the entire Continent looks ripe for the taking. In response, many European countries have banded together, and with American aid form the Allied Forces. Thus, an alternate World War II rages, fought this time around with more powerful and exotic weaponry. All the while even more unforeseen changes loom over the horizon.

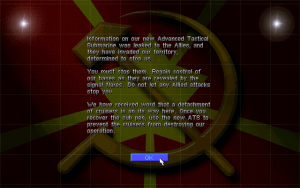

The campaign mode does what it could to flesh out that setting, helping make it familiar yet distinct even from its own successors. Playing as a nameless commander serving either the Allies or Soviets (with 15 missions each), you’re thrust right into the thick of the war, whether it’s to hold back the Red tide or spearhead the conquest of Western Europe. Carried over from Tiberian Dawn meanwhile is the option to choose which target locations certain parts are set in. While this amounts to little more than changing the map and scenery (barring a few missions set inside buildings), when coupled with a timer and statistics at the end of each mission, it adds more replayability to an otherwise linear backdrop; as an added touch, you occasionally even revisit the same maps for different objectives, with whatever you built previously still present. The plotlines tying these all together are told primarily through FMVs and prerendered CG cutscenes, which play before and after each mission. Compared to the original Tiberian Dawn, the writing has been given more emphasis to further add a cinematic flair. There are also more developed characters involved, ranging from Nikos Stavros, an increasingly vengeful Allied officer from Greece (played by Barry Kramer) to the calculating, manipulative Nadia Zelenkov of the NKVD (Andrea Robinson) and Stalin himself (Eugene Dynarski); the Allied route also introduces the infamous Tanya Adams for the first time (Lynne Litteer), as an American “volunteer” commando. Compared to later entries in the series, however, the tone is decidedly serious if not grim at points, even with the hammy acting or fantastical technology; the latter’s inspired by conspiracy theories and science fiction from the early-mid 20th Century, such as the Philadelphia Experiment and Nikola Tesla’s more exotic research. This is more evidently seen in the Soviet route showing them as unabashed bad guys, featuring among other things the massacre of a Polish village and Stalin purging supposed “enemies” among his inner circle, while frightening at least one officer into defecting to the Allies. It’s not for nothing that the game’s been hailed for being shockingly accurate in portraying Stalinism, right down to the dictator’s paranoia.

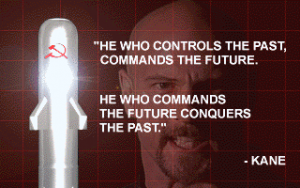

The tone isn’t the only thing that may seem out of place compared to later Red Alert games. It’s also the fact that the game’s connection to Tiberian Dawn runs beyond having similar graphics (utilizing a modified version of the same 2D graphics engine) or a largely conventional aesthetic. There are references to the original sprinkled about in the campaign, be it in the Allied route hinting to the eventual founding of the Global Defense Initiative or Joseph Kucan playing the role of Stalin’s secretive adviser, who’s all but said outright to be the infamous Kane; Kucan’s voice even appears at the end of the game’s creative installation screen. This extends as well to other aspects of the game, such as the predominant color used by the Allies being yellow/gold, the Soviets having a unit heavily derived from the classic Mammoth Tank (even having the same name), and how the graphics use some assets (like vehicular units) lifted straight from its predecessor. These aren’t a coincidence, as Red Alert was originally intended by Westwood to be a prequel; indeed, the game was initially planned as an expansion pack before the developers realized its potential as a stand-alone work. The effort, however, is not entirely consistent, especially regarding which order of events better matches up with the Tiberium timeline; the Allied and Soviet endings in particular, despite rather different outcomes, both contain elements foreshadowing the First Tiberium War. But while this move sparked debates among fans regarding the connections between the two universes, which still persist this day, this has helped give the game and the budding franchise a layer of depth that hadn’t been there previously.

The tone isn’t the only thing that may seem out of place compared to later Red Alert games. It’s also the fact that the game’s connection to Tiberian Dawn runs beyond having similar graphics (utilizing a modified version of the same 2D graphics engine) or a largely conventional aesthetic. There are references to the original sprinkled about in the campaign, be it in the Allied route hinting to the eventual founding of the Global Defense Initiative or Joseph Kucan playing the role of Stalin’s secretive adviser, who’s all but said outright to be the infamous Kane; Kucan’s voice even appears at the end of the game’s creative installation screen. This extends as well to other aspects of the game, such as the predominant color used by the Allies being yellow/gold, the Soviets having a unit heavily derived from the classic Mammoth Tank (even having the same name), and how the graphics use some assets (like vehicular units) lifted straight from its predecessor. These aren’t a coincidence, as Red Alert was originally intended by Westwood to be a prequel; indeed, the game was initially planned as an expansion pack before the developers realized its potential as a stand-alone work. The effort, however, is not entirely consistent, especially regarding which order of events better matches up with the Tiberium timeline; the Allied and Soviet endings in particular, despite rather different outcomes, both contain elements foreshadowing the First Tiberium War. But while this move sparked debates among fans regarding the connections between the two universes, which still persist this day, this has helped give the game and the budding franchise a layer of depth that hadn’t been there previously.

There’s more to Red Alert, however, than similarities and connections. The game in particular makes a number of changes that would become mainstays (in one form or another) throughout the series and franchise at large. One notable example is the introduction of a proper, offline skirmish mode. For the first time, you get to play against AI opponents across various maps. Alongside the Mac port of the original, the game also marks the introduction of proper, online multiplayer straight out of the box (initially through Westwood Online), allowing gamers across the world to not only play matches against each other but also communicate through Westwood Chat; ever Westwood closed down, fan-run servers like XWIS and CnCNet still make online multiplayer very much viable. Coupled with more variable settings (such as adjusting in-game speed), these developments help prolong longevity while marking a step up from Tiberian Dawn, which only offered LAN multiplayer against other players until the “Gold” edition came out in 1997; it’s no surprise then that all Command and Conquer games ever since have these as standard.

The game also shakes things up a bit regarding the two playable factions. Superficially (and much like in Tiberian Dawn) the Allies and Soviets share many units and sprites, barring the looks of certain buildings like their respective barracks, and to a degree share similar tech trees; like other Command and Conquer games made by Westwood, unit types are unlocked by building the appropriate structures, with no upgrades. This time around, however, the differences are made more pronounced. On top of having each side have different-accented voices, Red Alert 1 for instance introduces the concept of sub-factions, through the form of having each side represented by a handful of playable nations – such as England and Germany for the Allies to name a few – in multiplayer; while these are bare-bones and provide no more than passive bonuses (like Soviet Russia having 10% cheaper units), they add more variety while foreshadowing the trend of greater differentiation down the line.

The changes also extend to gameplay and the variety of units that can be deployed, with an eye for being competitive in multiplayer. The Soviets, for instance, emphasize heavy firepower and brute force, which is reflected in their wider selection of aircraft (such as Hinds and MiG fighters), their use of electric, Tesla-based defenses and how their basic Heavy Tanks can defeat their Allied equivalents in open combat. The Allies meanwhile emphasize speed, cheaper units and flexibility, be it through the ability to keep infantry alive through Field Medics, using Minelayers to help set up ambushes and traps, or using commandos like Tanya to turn the tide from behind enemy lines. The new superweapons each have (on top of the nuclear weapons both have access to) also add new strategies that play into their strengths. The Allied Chronosphere can transport a vehicle across the map and straight into an enemy base for a limited time, while the Soviet Iron Curtain grants even a Mammoth Tank temporary invulnerability to any attack while active; that said superweapons are also lethal to infantry also open up other offensive possibilities that utilize these beyond their intended purpose.

In terms of gameplay, Red Alert builds upon what worked with the original, while also adding a number of innovations that go past simply replacing Tiberium with ore as the main resource. Naval warfare is properly introduced into the series for the first time, opening up new possibilities in terms of strategies (such as amphibious landings or shore bombardments) and map types that had previously been reserved for scripted campaign missions. Likewise, is the introduction of espionage as a viable tactic, as seen in the Allies’ use of Spies and Thieves – which can disguise themselves as the enemy to infiltrate buildings for intel and sneakily steal funds from refineries, respectively – and Soviet Attack Dogs being able to sniff out and kill interlopers as easily as regular infantry. There’s also the inclusion of “gems” as a special resource that’s non-renewable but is more valuable in terms of income, an aspect that in one form or another would become a recurring background element in later games. In addition, the game incorporate features into the interface that have since become standard in many RTS outside Command and Conquer, such as allowing you to query commands, select many more units at once and setting up unit groups through the control key; such innovations help lower the learning curve and make the game more intuitive, thus freeing you to focus more on dealing with opponents. Combined with good pathfinding, these all contribute to further honing the formula characterizing much of the franchise; this can be seen from the flexible rock-paper-scissors dynamic and the use of engineers for insta-capturing enemy buildings to fast-paced carnage and the thrill of running over hapless infantry with tanks. Even to this day, the resulting action holds up rather well, all the while complemented by solid sound design and a soundtrack courtesy of Frank Klepacki (who even played a minor role in the FMVs); the first iteration of the now classic “Hell March,” serving as the game’s theme song, was even awarded the best video game soundtrack of 1996 by the likes of PC Gamer and Gameslice.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t any blemishes. The introduction of the skirmish mode, while helping extend the game’s longevity gets repetitive after a while due to the still rudimentary state of the AI. The graphics, while sharper and otherwise holding up well for being over 20 years old, still show their age; this is particularly evident in the low-resolution sprites and the engine’s limitations in rendering urban areas. The game itself, especially in its original state, can also be hard to play on modern systems due to compatibility issues, unless you have the compilations released by EA (be it The First Decade or The Ultimate Collection), tweak the settings just right or find some workaround online.

Even with those flaws in mind, it doesn’t diminish how exceptionally good Red Alert was at the time, selling 1.5 million copies worldwide within the first month of its release and winning the “Best Strategy/War Game” Spotlight Award from the Game Developers Conference in 1996. Neither does it diminish the significance of this game in both influencing RTS as a genre and setting the stage for future titles in the series. That it holds up remarkably well after all this time also helps considerably in that regard. Though it wouldn’t be long before the seeds planted would bear much fruit.

From a technical perspective, Red Alert comes in both DOS and Windows flavors. The DOS version, from a technical perspective, is the same as the first game, as it runs in VGA. The Windows version runs in SVGA, but since it uses the same sprites and tiles, it simply zooms everything out, giving a wider viewpoint. Here, the sidebar is also mandatory, where it can be hidden (and unhidden) in the DOS version. The cutscenes are also interlaced in the Windows version, due to upscaling from their original low resolution format.

Beyond its initial IBM PC release, Red Alert was also ported to the PlayStation. It’s a substantial improvement over the 32-bit ports of the original – it supports the mouse, as well as the System Link cable, so you can play multiplayer if you have two systems and two televisions. As with the computer versions, since it comes on two CDs, each player can use one on their respective system. Due to the system’s low resolution, the visuals are about the same as the PC version in VGA, though the sidebar menu can now be transparent. Using the controller, you can switch back and forth from the menu with the Triangle button. The cutscene quality is a bit better, too. Strangely, the music selection has been changed so it no longer features track names, using numbers instead. Overall, for a console port of an RTS, it works pretty well. For the most part, it’s not really worth playing for anyone with access to a computer that runs it, but it has been released on the PSN, so it’s playable in portable format on the PSP and Vita.

Command and Conquer: Red Alert Expansion Packs (Retaliation)

In the wake of Red Alert’s success, the prospect of an expansion pack was all but expected. What happened instead, two were released in 1997: Red Alert: Counterstrike and Red Alert: Aftermath, both with the “apprenticeship” of Intelligent Games (which later on world work on Tiberium Wars: Kane’s Wrath). Unlike those of later Red Alert, let alone other Command and Conquer games, these are expansions in the most technical sense, as both feature added missions (for Allies and Soviets alike), new units and new maps; Counterstrike in particular is notable for introducing four hidden “Ant Missions,” in the style of 1950s B-movies. In 1998, both these packs were bundled together into Red Alert: Retaliation for the PlayStation, featuring new FMV cutscenes even for the aforementioned “Ant Missions.” Put together, all these not only help expand the base game’s popularity, but also signify a pivotal point in the series’ direction.

The new campaign missions (17 for each faction in total) act like side stories taking place during Red Alert’s take on World War II but go a bit further than that. Retaliation in particular brings said side stories, which until then were generally more like stand-alone affairs, together into a more cohesive narrative. This time around, you’re placed in the shoes of a commander assigned to either an Allied or Soviet auxiliary command, the former in particular as part of an American detachment following the United States’ full entry into the conflict. The missions themselves are rife with various scenarios (including ones set indoors) and as action-laden as the main game, though noticeably harder as they seem to assume that you’ve already beaten it. But arguably the main draw is in gradual shift in tone seen in-game and come Retaliation, in the FMV cutscenes. The missions (especially the ones from Aftermath) introduce new, more experimental units for both sides that lean even more on the “super-science” established previously. The FMVs further build on this shift in tone, particularly through new characters introduced. For the Soviet missions, for instance, there’s General Topolov (played by Alan Charof), whose weary yet friendly demeanor adds a layer of ambiguity to the USSR, highlighting how not everyone’s on board with Stalinism. While the Allies have General Ben Carville (played by Barry Corbin of WarGames fame), a patriotic American eager to do his part against the Commies as one of the “good guys,” delivering a performance that’s at once campy yet grounded. Though the result is still rather consistent with the wider backdrop, it foreshadows the direction the series would take in the future.

Then there are the other additions, particularly the new units and weirder touches. From campaign-only fare such as the Soviet cyborg commando Volkov and Allied Phase Transports to fully accessible ones like Allied Chrono Tanks and Soviet Tesla Tanks (introduced in Aftermath), the two factions now have access to a more varied arsenal to take on enemies that further build on their existing strengths while potentially opening up new tactics. The non-canon “Ant Missions” meanwhile add considerably more challenge than what the hokey ‘50s B-Movie presentation (with Gen. Carville in the FMVs) initially makes them seem, especially when said hordes of giant ants can overrun a base if you’re not prepared. When put together and coupled with cheat codes like “Soylent Green” that turn ore into harvest-ready people, the result is a more concerted effort by the developers to distinguish Red Alert from the Tiberium timeline.

This effort, while not all-encompassing so as to turn Red Alert into an entirely different game, isn’t enough to make too much of a significant impact. Indeed, a recurring criticism from games journalists, particularly by the time Retaliation came out, was how the expansion packs offered in many respects more of the same. This was on top of how playing Retaliation on the PlayStation tended, much like the port for the main game, to be simultaneously finicky and difficult, thanks in part to a steeper learning curve; that the FMV cutscenes are not available to the PC expansions (unless the “Lost Files” mod is used) also tends to be considered another glaring issue.

Given the solid action and gameplay seen in the main game, however, these negatives pale in comparison. They certainly didn’t dissuade gamers from buying these expansions in droves, nor did such criticisms really tarnish the reputation of the Command and Conquer franchise in any meaningful way. Counterstrike in particular sold 650,000 units by October 1997, which according to Westwood, made it the fastest selling expansion pack for a PC game at the time.

Such popularity would not only keep the budding Red Alert series alive among RTS fans and gamers at large. But in addition to the emerging sense of a distinct identity, would help set the stage for the sequel.

Fan Showcase: OpenRA

On August 31, 2008, as part of Command and Conquer’s 13th anniversary, EA officially made Red Alert 1 (along, de facto with its PC expansions) freeware. By then, the game had seen its fair share of mods and online communities emerge, even well after its prime. But at the same time, growing compatibility issues made the game (already showing its age) harder to run at all. Within two years of the freeware reveal, however, a more ambitious project would emerge coming from the very fans and modders keeping the franchise alive. The fruit of that labor is OpenRA, an open source game platform that modernizes Westwood’s 2D classics while staying true to the spirit of the originals.

First released in 2010 for PC, Mac and Linux, OpenRA is a work in progress (“release-20180307” as of this post), having evolved over time to accommodate custom mods and even original works; in spite of manpower issues, there are still plans to eventually make Westwood titles made after 1998 (like Tiberian Sun) fully playable. All the same, among the main draw remains how the platform manages to replicate the graphics engine used in Tiberian Dawn, Red Alert 1 and Dune 2000, effectively recreating those games from scratch without the need for emulation. As an added touch, the recreated “mods” utilize the original assets, right down to the sound effects and voices; there’s even an option to include the FMV and CGI cutscenes, if you have the freeware copies and/or original CDs. These alone are impressive for what’s for all intents and purposes a fan project.

OpenRA’s other big selling point concerns the “modernization” aspect, which go past making Red Alert 1 compatible with modern graphics cards. Indeed, the programmers behind the project use the opportunity to incorporate over a decade’s worth of updates instead of just replicate an exact clone of Westwood’s engine. These improvements run the gamut from high screen resolutions, “left click/right click” options and tweaking the range of certain units to added graphical effects (like planes leaving contrails) adding a Generals-style fog of war and using a streamlined sidebar interface derived from Red Alert 3, among others changes. Even with such a mish-mash of old and new, what’s rather surprising is how much of the core gameplay remains intact, or at least staying true in spirit to the original. Add in integrated online multiplayer, complete with the kind of features that you’d expect from more contemporary RTS game (such as replays and support for livestreaming), and the result is a rather vibrant, competitive scene that continues to attract attention from long-time fans and newcomers alike.

It’s not a surprise then how fan works like OpenRA have helped considerably in keeping Red Alert, let alone the franchise alive. But the series it laid the groundwork for had only just begun.