- Z

Oh, the early days of the real time strategy game on DOS PCs. After Dune 2: The Battle for Arakkis birthed the genre as we know it, it was further refined with Warcraft, before coming into its own with Command and Conquer and Warcraft II. During this time in 1995, before the glut of me-too ripoffs, before Westwood and Blizzard published their own successors, there was Z (officially pronounced “zed”.) Z is the creation of The Bitmap Brothers, a small British studio who found some measure of success with Amiga titles like The Chaos Engine, Xenon and Speedball. According to them, it wasn’t developed to cash in on the new RTS craze – its timing happened to be coincidental, since the game had been in development for several years, long before the genre became trendy.

Z is probably more likely inspired by the Genesis game Herzog Zwei, or even more likely, the similar Nether Earth, an early title for 8-bit computers. Now, as the RTS genre progressed, gamers began to criticize Command and Conquer for being too “arcadey,” because it seemed to rely more on simple tactics than true strategy. If that’s the case, then Z makes Command and Conquer look like Nobunaga’s Ambition. But that’s definitely not a detriment, at all – if anything, Z‘s focus on fast paced action is what makes it so particularly unique.

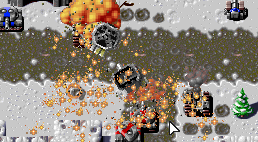

The conflicts are broken down into two teams of robots: Red and Blue. Each level places their base at opposite corners of the map, which is divided into several symmetrically divided territories, each of which has a flag. Touching the flag will capture the territory, which usually has some kind of structure. The most useful are factories, which have predesignated tasks – some will create infantrymen, others will create tanks, still others will create turrets. They operate automatically, with a timer on top that indicates how long it’ll be until it pumps out the next unit. The more territories you have under control, the quicker you’ll manufacture units. Depending on the capabilities of each factory, you can change the type of unit to create, and it will happily churn them out, until you tell it otherwise, or it gets taken over by your opponent. Obviously, more powerful units take longer to create.

It doesn’t take a genius to realize that you need to grab and maintain as many territories as quickly as possible. It’s all too easy for territories to ping pong between players, as capturing or losing several territories at once will drastically alter the balance of power. Since there’s no time to sit around and stock up units, it requires you to be proactive and think on your feet. Each stage is usually littered with empty vehicles, waiting to be commandeered.

There are several types of infantry robots – Grunts, the standard weaklings; Psychos, who wield machine guns; Pyros, who use flamethrowers (which are a bit disheartening because nothing ever really catches on fire, since everyone are robots); Snipers, who can pick drivers out of vehicles to steal for your own side; Lasers, who obviously wield lasers; and the slow but powerful Toughs, who wield rocket launchers. There are also the usual vehicles like APCs, jeeps, and several varieties of tanks. Although each robot class has their own weapon, any of them can pick up grenades boxes, which are strewn throughout each stage. These have limited ammo, though, and the boxes don’t respawn after being picked up. You can shoot them too, which causes a huge storm of grenades to be flung around the immediate area.

Your robots are lively bunch, inquiring and responding to your orders per usual RTS standard, but they’ll also yell and curse at you if they’re under attack, or cheer ecstatically when you’ve blown up the enemy base. Their portraits pop up in the upper right portion of the screen, with perfectly lip-synched voices, at least in the English versions – THAT’S attention to detail. You can occasionally catch them shooting at birds or random wild life, just for kicks. There’s also a secondary voice that announces when vehicles are manufactured, that’s perhaps a parody of Command and Conquer‘s EVA, as she speaks with a bizarre accent that sounds part Texan, part Australian. The MIDI music respond dynamically to the situation, pumping up from quiet and atmospheric to exciting and triumphant as you run into conflict. The voices, sound effects, and music in unison work astoundingly well, especially as you near victory.

There’s a barebones plot that ties everything together, with some rendered cutscenes showing the robots blowing up things, flying from stage to stage, and generally just screwing around. At the forefront is General Zod, the cigar chomping Colonel, along with his surfer dude subordinates Brad and Allen, whose hijinks set the tone for each of the game’s twenty single player stages.

Z was in development for a number of years, and according to The Bitmap Brothers, much of this time was spent developing AI routines. Considering that even the original Command and Conquer had very simplistic computer opponents that mostly relied on scripts, this is pretty impressive, but sometimes it falls a bit flat, particularly when guiding your own units. For instance, if they’re close enough to a flag or a vehicle, they’ll automatically hop into it without being explicitly told to. This is handy, except when you’re directly telling them to attack something (like, say, a gun emplacement) and they ignore you to do their own thing, and get themselves killed in the process. The pathfinding is also a bit suspect – the vehicles are programmed to drive on roads, since they move faster, but sometimes they’ll take an extremely roundabout route when there’s a much more direct one available. Sometimes the robots will do stupid things like wasting grenades to blow up mountains, when it’d just be smarter to walk around them. In disregard of these handicaps, the game is hard. The computer is often brutal, and in the later stages, often expands quicker than a mere human could ever possibly act.

The original version of Z runs in DOS, in either VGA or SVGA resolution. The VGA resolution feels a bit cramped, while the SVGA resolution uses the same artwork but features a zoomed-out viewpoint, making it the preferred way to play the game. It was also ported to the PlayStation and Saturn, but these versions were only released in Europe.

A bit after the original release, The Bitmap Brothers ported Z to Windows 95, termed Z95, with a few tweaks and enhancements. The VGA display has been removed, and there are now options for difficulty and speed. This is actually really handy, because the movement is actually a bit slow in the DOS version, and the whole game feels much better when sped up. Also included are a total of 15 new single player missions, although many of these are just expanded versions of older stages. There is also an included map editor. It won’t install properly in Windows XP, but a patcher can enable everything to work correctly.

In 2011, Kavcom released a port named Z The Game for iOS devices, which uses a new, modular on-screen display to leave more space for the main view. This was also ported to Android and Blackberry the following year, which is more pretentiously named Z Origins.