Indie games have a difficult time standing out. Many go the safe route and pay homage to old genres or famous titles, or even periods of the medium, and some of these light the gaming world on fire. However, this is rarely the case. For every Super Meat Boy or VVVVVV, there’s several dozen failed point and click send-ups and retro platformers with changing graphical styles. If an indie game doesn’t have the resources to capture the public’s attention with strong mechanics or incredible sights, the best way to stand out is to be completely different. That describes Always Sometimes Monsters to a tee, a narrative heavy game about a bum trying to find their personal happiness, while also surviving the harsh streets of the city. It helps one of the developers was a bum for a good bit and mixed their experiences into the game proper.

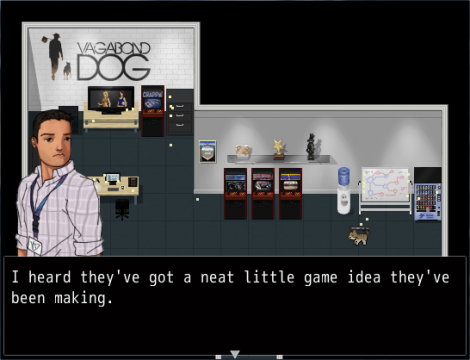

The first release by indie developers Vagabond Dog, Always Sometimes Monsters is a game that defies usual genre conventions of …well, any gaming genre. It’s an RPG Maker made title, but it’s not really an RPG. It’s not a normal adventure game, as there’s no complicated puzzles to solve in order to progress. It’s also not a narrative focused walkabout, as there is urgency at nearly all times and a heavy emphasis on player choice. It’s a strange hybrid of these genres that becomes something else entirely, and it’s all backed up by the blunt dialog and provoking themes of choice and morality.

The heads of Vagabond Dog, Justin Amirkhani and Jake Reardon, inserted themselves in game to spout some meta commentary at certain points, and the two usually do their best Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in the process. Sometimes, though, they’d make comments about what Always Sometimes Monsters was supposed to be. In the first area of the game (where you can manually control a character’s movement), you can find them hanging out in the corner. They’ll ask your opinion on a game idea where the player may not end up being the good guy, giving a huge hint for what’s to come for the next several hours. The game they finally decided on is one filled with choices, one that plays with morality, yet has no morality meter that rates how good or evil you are. What they’ve made is a game that isn’t simply a game where you play the bad guy, but one where you may simply not end up being the good guy. That’s the big difference here; Morality is how you interpret your choices and their outcomes, and the choices that benefit you may not always be the ones that are “right.”

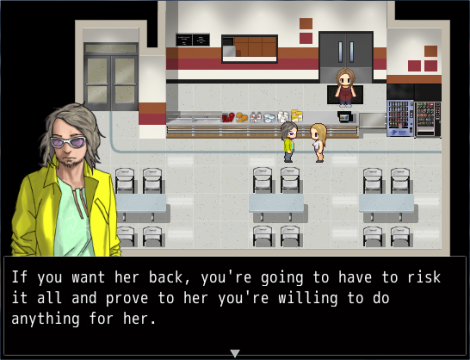

The premise is that you’re a down on their luck writer who blew off their publishing contract and lost the love of your life just a few months ago. You’re a wreck, you’re being kicked out of your apartment, and when you finally get compensation from your contract, it’s barely anything because of your lack of results. Possibly worst of all, your ex is getting married to someone else down in California, across the country, and you need to get there in thirty days to win them back. What happens from this point comes down to the choices you make, both big and small, and the outcomes are rarely obvious.

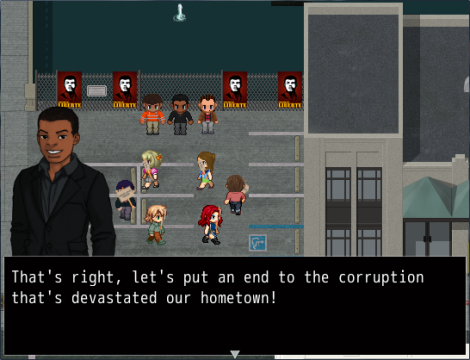

The game is divided into three main cities and a variety of smaller areas. Your goal is to earn enough scratch to both eat regularly and buy a bus ticket to the next stop on the way. However, you can also find rides from other characters if you make the right decisions, though you can also lose those rides if you’re not careful. For example, when trying to leave the first city, a character from the job segment will give you a ride if you say the right things …but another segment involving a doctor can bring an unexpected consequence to that plan. Every section of the game functions this way, with unexpected possibilities hiding behind each corner, and these choices can pile up into being ultimately nothing of consequence or completely changing your current situation. These different paths aren’t initially obvious either, such as the three main branches for solving the strike issue in Beaton, which require you to do as you’re told or reject the paths you’re given to find a third, though at a massive cost.

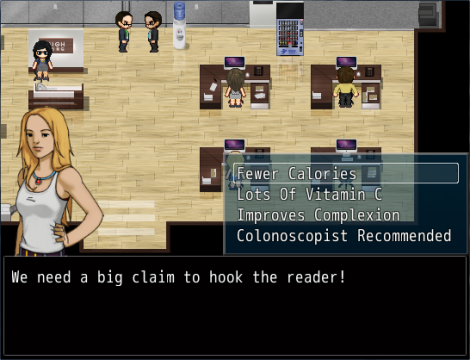

Some choices present themselves as temptations. For example, when helping out an elderly lady and picking up some groceries, you can also rob the area behind the store after meeting a man looking for a sandwich just on the side of the building. Others are more vague, such as an odd interview for a paper with an ex-advertisement designer. There’s usually an option present that nets you fast money, but it could lead to massive fallout later …or none at all. The game keeps the player on their toes by never making it clear whether a decision is important or not, making the major decisions all the more meaningful when they do pop up. This said, there is a moment towards the game’s end where another character reads your character’s diary (assuming you’ve remembered to write in it, as your old publisher has promised to publish it) and questions them on if they’ve regretted any of their horrible actions. You can deny guilt, but you may be shocked by the response that comes out of your character’s mouth. The real impact from the decisions of Always Sometimes Monsters is not from missing out on money or a ride out of town, it’s the impact you have on the lives of the people you meet throughout your journey.

You can be a small note on someone’s life story, or be the central interloper that changed everything – including bringing the story to an end. By the end of your journey, you may have accidentally killed several people – or possibly have done the deed on purpose. It’s equally possible that you managed to be the nicest person imaginable, though it may not bring you the end result you wanted …or you get exactly that. There are countless variables at play and a large, an always changing cast and shifting settings, so the end you get can be difficult to see coming, unless you’ve managed to put a lot of focus on how the game functions through several replays.

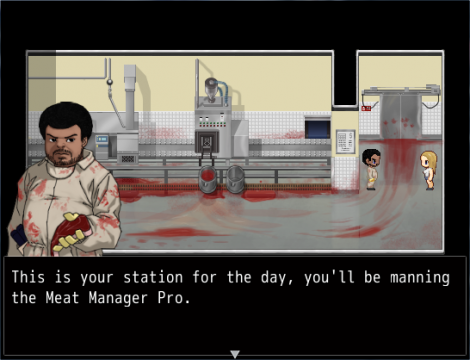

The game’s major strength comes from dialog, created from real conversations the developers had. Characters speak in very real ways, especially when heavy subjects are brought up, and it comes with all the dialects and slang you’d expect to hear. A few characters go a bit far into cartoon territory, but you may still get a moment of clarity that reveals hidden depth in these supposed cutouts. This is pulled up particularly well with a drug dealer’s nephew, if you decide to go to his house to get payment for a ticket he wants. There’s no shying away from the darker side of the world either, including prostitution, political corruption, theft, the life and death struggle the homeless deal with every day, and so on and so forth. One particularly stomach turning section has you working as a coat checker at a local nightclub, and you have to be supportive and give back coats quickly for good tips. However, for a few moments, the game implies you’re assisting in a horrific crime by doing things by the book, including giving someone the opportunity to sexually harass an injured woman outside. The dialog of characters like these is blunt and strikes hard, as it’s incredibly easy to read between the lines and gets you to start questioning your actions, leaving little doubts in the back of your head for awhile after.

Dialog also changes based on your chosen character. At game start, you can select from various possible versions of the main character, and you can choose who will eventually become your lover and ex. This allows you to choose not only your gender and race, but also your sexuality, which can be clarified further during the game proper in a few conversations. These factors completely change how some characters will react to you, which can completely change the context of a scene. The job with the factory foreman is completely different as a white guy then it is as a lesbian, for example. This allows the game to be very inclusive and deal with subjects related to sexuality, like the emotional issues transgender people deal with, or prejudice faced by openly gay individuals. It’s something very simple that goes unnoticed during play, yet somehow a feature countless major developers struggled with including around the game’s original release. Always Sometimes Monsters released at a time where people were begging major developers to create more inclusive protagonists or options to make their own, making it part of a counter-trend of inclusive casts and character options that was made popular by Saints Row 3 and 4.

The game does have proper gameplay in a series of little minigames, such as a hacking challenge that plays like Frogger, but the game proper simply asks you to move around and talk to people. This works perfectly fine for what the game is trying to do, avoiding any ideas of player empowerment or complex challenges for real world grind and frustration. It fits the story, and the minigames end up being what feels most out of place. Several of them also come off as poor knock-offs of more popular arcade and phone games, like then popular Flappy Bird and old school, carnage heavy arcade titles. They’re cute jokes poking fun at trends in the industry, but not much else.

The game’s size is far larger than you’d expect. I have 30+ hours and multiple playthroughs down as of writing, and I’ve only scratched the surface of possible events. There’s almost always something you’ve never seen hiding in a corner or somewhere on the side, like a character previously unexplored with their own story, or an area previously inaccessible. A single play can take about seven to twelve hours if you go in blind, and about five to seven on secondary plays, but that time can increase substantially the more you explore. There are also tons of alternate solutions to different problems you encounter, including gathering food. The game can reward exploration and experimentation, though it can take some time to learn all the tricks hidden.

The graphics are solid enough for a game made in RPG Maker, with simple background sprites, though some made with custom pallets, along with several custom items in every area. Character sprites are distinctive, while character art can balance between roughly well presented to a questionable mess (several of the possible player or “Sam” designs are poorly proportioned). Thankfully, the music more than makes up for it, with a focus on electronic and bass heavy pieces. Every track has an urban feel to it, both harsh and steady, but not entirely unpleasant. They mix into the background perfectly, but can completely overpower the atmosphere at just the right moments, like during the mania of a live performance at a night club. These pieces add a lot to the presentation, as do the strong sound effects.

Always Sometimes Monsters ended up becoming an award winner, snatching away Best Writing and Best Indie Game at the 2014 Canadian Videogame Awards, fending off strong competitors like Ubisoft’s Child of Light and Capybara Games’ Mercenary Kings. The game, thanks partly through it’s very low budget, made profit just a few hours after initial release. It became one of the major indie success stories of 2014, yet didn’t become one of the most talked about games of said year. That may be fitting. Always Sometimes Monsters is a game of equal parts failure and success, and finding one’s place of happiness or content within that mixture. Vagabond Dog was amazed by how many people liked their weird, pretentious game, and they’re certainly happy with the outcome of their choices, even if it isn’t the greatest possible result. Life is how we make it, and we have to accept that. Ultimately, that’s one of the major messages of Always Sometimes Monsters, and one to take to heart.

Links:

Always Sometimes Monsters Vagabond Dog’s website for Always Sometimes Monsters.

Always Sometimes Monsters Devolver Digital’s official website.