by Nilson Carroll – February 23, 2016

Tao is so strange, so inexplicably weird, and almost completely unknown and undocumented that it is legitimately mysterious. It’s not genre defying like Capcom’s cult hit Sweet Home, nor is it as bad as Hoshi wo Miru Hito, nor as genuinely good as Lagrange Point. As far as 8-bit JRPGs go, Tao is mediocre, sometimes frustrating and obtuse. But there’s something special about it. It is a mythic piece of unexplainable software, as weird as something like Monster Party.

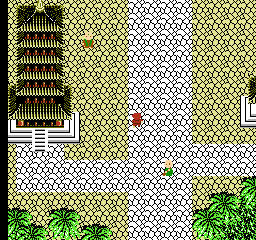

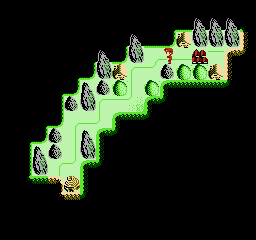

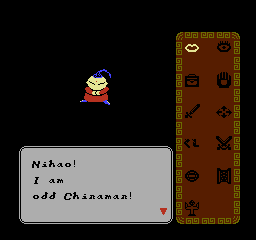

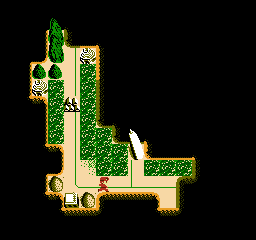

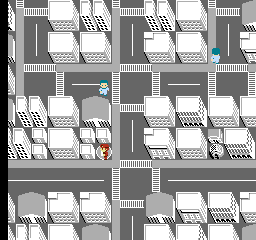

Playing Tao is tedious. It is a Dragon Quest clone in the way that most Japanese RPGs released in the years following Dragon Quest are, with a division into town maps, world maps (which are narrowed down into linear paths by a thick black fog), and random encounters. Approaching an object, location, or NPC, triggers a menu with a bunch of redundant adventure game interactions, similar to the first Dragon Quest, which are represented by evocative Chinese characters in the original game but shown as icons in the fan translation. This translation apparently was forced to many compromises due to text length limitations, so most NPCs speak in a cryptic shorthand style. With a little luck, the NPC activates a flag for the story to move along. But moving through cities is a hassle, as NPCs can block narrow passages, forcing players to wait or take a longer route, opening them up to the dangers of more random encounters.

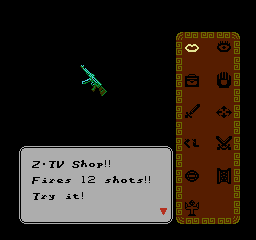

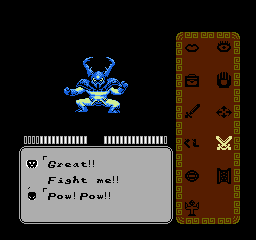

Battles are an unintuitive mash of the A button and that’s it, aside from a few items that can be used later in the game, including one that transforms the protagonist into a demon. A few of these are enough to be tiring to the hands. The sole adventurer does level up with experience and can purchase and equip a gun. Without grinding steadily for each new wave of stronger enemies, the game can become impossibly difficult. Tao has the bare necessities of what makes a JRPG, but these elements only get in the way, making the game a real chore to play.

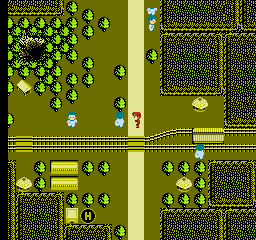

While adhering to many genre tropes, Tao is very much unlike the rest of its peers in a different department. The adventuer starts in what seems to be a pre-1900 version of somewhere in East Asia, except for the modern train station and the helipad that can be found in the starting town. The box artwork shows an Akira Toriyama reject hero standing next to some train tracks and a tyrannosaurus rex, with a smog-covered city seen in the background. Digging a bit further, the game seems to take place not in the past, but the future, making Tao more similar to the Megami Tensei series than traditional fantasy RPGs (especially the large Tokyo area is reminiscent), a spiritual science fiction narrative full of demons and pseudo-religious references.

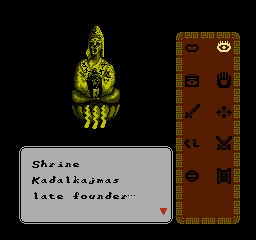

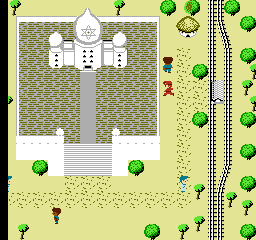

The first five minutes of the game are spent carrying an old woman to a Buddhist shrine, where she turns into a demon, steals a scroll, turns into a giant, and then disappears. While the monks philosophize on the meaning of being, the head priest decides to send the protagonist on a quest to locate the eight elements of the trigram. The priest gives the protagonist his element, a block of wood. Not even Tao, as different as it is, is immune to the orb collecting JRPG trope. Another central plot element involves a strange meteorite that crashed into town (mind that this was made by the company who developed Mother with Nintendo). The protagonist returns to town, where the train station is now open, which is arbitrarily convenient.

These arbitrary story flags plague the entire game, more so than any of its other JRPG peers (which means it is pretty bad). The first few moments in the game are confusing, but easy enough to trudge through. Later, when random encounters become a thing in towns and on the world map, talking to every NPC again and again becomes a real chore. Due to this, it’s best to play Tao with a guide.

One such guide is provided by the game’s fan translator, Snark. Following the guide, players will quickly reach a point where Snark writes: “Ride the dinosaur to Moskva.” So the protagonist rides a dinosaur to Moscow. For a game with a dinosaur on the cover, it’s hilarious that it is merely a Flintstones-style mode of transportation which the player accesses through purchasing a train ticket. Nowhere else in the game does this tone of wacky science fiction exist.

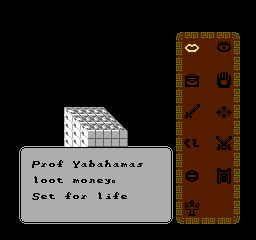

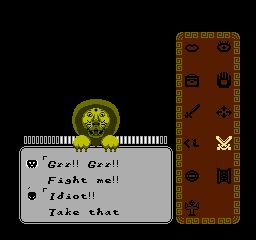

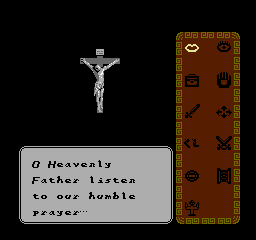

In Moskva, players visit a cathedral, and there are NPCs that complain about donating to the church when they don’t believe in God. The plot spirals out of control quickly, as a hunter hoarding a pile of cash, a fight with a three-eyed lion, something about constellations, and rumors of an evil billionaire in a tower lead the player to Crosston, the “Christian town” (get it?). Here, the “Christian” NPCs are contrasted strongly with the Buddhists met earlier, and it’s difficult to tell with the slight dialogue, but the NPCs appear to be depicted as intolerant of the other religions.

What follows is a series of back and forth fetch quests and event flagging between the different locations. There are a handful of boss battles with enemies such as Hindu god “Ganesh” and the “Cosmos God Mochona”, a god worshiped by a cult in the game. At some point, the helipad becomes active and players can ride a pink pterodactyl around.

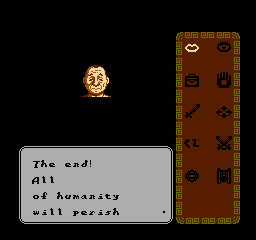

Eventually, the protagonist meets Ridley, the billionaire in the tower, who demands some sacred items. This quest ends up getting the protagonist thrown in prison, where he shoots police officers with an automatic weapon (if he bought one earlier). It’s a lot to take in. While collecting the sacred items, the protagonist revives a mummified Buddhist deity, who explains that he was mummified by his followers because they did not like his teachings, making the religion a total sham. It’s one of the few truly interesting and fleshed out scenes in the game, and even the monks break down in tears.

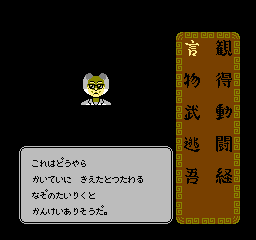

The game constantly seems to be expounding some religious commentary, but much of it is buried deep. As more details of the world’s cosmology are revealed, Tao hints at having Yiguandao themes. Yiguandao (meaning the Consistent Way) is a real world Chinese religion that was outlawed in China in the 1940s, but still exists today and has many followers in Taiwan. A monk in Tao describes at length the Wusheng Laomu, or Unborn Ancient Mother, making this possibly the only Yiguandao video game in existence. Later, the mummified deity explains that all modern religions are warping the truth, and that Raum (the game’s version of the Unborn Ancient Mother), who gave birth to all souls, is the only path to salvation.

In contrast to almost all other JRPGs of the 1990s, Tao is entirely pro-organized religion. While most JRPGs give the player the okay to fight creator gods and place the power of friendship over the power of faith, Tao seems to exist to spread the message of Laomu. It’s difficult to call the game propaganda, but it does make one wonder how sincere the developers were when writing the plot. It recalls Xenogears‘ relationship with Gnosticism, but the text is so slight, the lines between theme and propaganda are impossible to distinguish. The game’s page on ROMHacking.net describes Tao as having themes in common with philosopher Umberto Eco, mystic Edgar Cayce, occultist Helena Blavatsky, Nostradamus, and The Matrix. Tao is, arguably, in some obscure, 8-bit way, sort of related to most of these items (not so much The Matrix), but its relationship with the Yiguandao religion is on the nose.

The music is a mixed bag, with the catchy/repetitive/mysterious crunch of the world map theme being a highlight. If nothing else, Tao can be praised for its assorted 8-bit sprites, interesting set pieces, and, of course, insane religious conspiracy plot. It’s moody, potentially controversial, and clunky. Those interested in the XZR series will find something of value in Tao.

Like Mother, Tao has a varied and complex, real world-ish plot, more so than any other game on the console. But in a lot of ways, it doesn’t quite live up to its name: a sci-fi Taoist Famicom JRPG with cults and real world ties should be mindblowing and completely mystical, but most of its presentation is mediocre and uninspired. Still, it’s one of the Famicom’s stranger footnotes, and definitely worth a playthrough.

Links:

ROMhacking.net Translation for Tao.

Tao Translator The Snark’s page for Tao, includes a walkthrough.