There are only two truly notable games in the Spec Ops series, the first and the last. Spec Ops appeared in the gaming world with Zombie Studios’ Spec Ops: Rangers Lead the Way, one of many tactical shooter franchises to appear in 1998, and one of many who fell to the grueling realism of Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six. The game got an expansion pack and a sequel from the studio in 1999, while a total of six (!) budget titles from smaller studios (including Runecraft, creators of that hit classic Barbie Super Sports) released from 2000 to 2002. The budget game garnered no fanfare or critical praise, and the franchise quickly vanished, only popping back up for a short blip when Rockstar mentioned rebooting the series when they gained the license, only to abandon the idea.

In 2006, a grunt worker and aspiring writer at 2K Games named Walt Williams was approached by his boss after his frustrating dealings in trying to rewrite Bioshock 2. His new script was thrown out due to being an act of vanity that was too late to implement, but was impressive enough to offer him a top spot on a series reboot of Spec Ops. Despite a distaste for military shooters, thanks partly due to his experiences in military school, he agreed, hungry for his own game to shape, one he could call his own.

After six years of development hell, with management suggesting more and more features to bloat the project whenever completion seemed near, Spec Ops: The Line hit store shelves and completely surprised audiences. A forgettable budget series from the late 90s that failed to stand out among its brethren had suddenly reappeared as some sort of Apocalypse Now riff that deconstructed not only the modern military shooter, but the relationship between games and the player, alongside showers of political commentary over US military culture. It’s a weird case where the inexperienced German devs, Yager Development, failed to match Battlefield and Call of Duty mechanically, but the narrative completely outweighed those faults in the eyes of critics and players. On top of that, the already snowballing games about games trend finally exploded out with Spec Ops‘ return, making the title somehow incredibly culturally important for the medium, yet a commercial flop.

The main campaign follows Captain Martin Walker and his squad, Adams and Lugo, arriving in Dubai six months after a huge natural disaster, where sandstorms destroyed the city. Evacuations efforts by the “Damned” 33rd, led by Colonel John Konrad, have seemingly failed, and Konrad has sent out a message asking for help after long silence. The trio have come to find any possible survivors and then leave to call an evac, but they quickly get involved in a bloody civil war among the 33rd, the CIA, and the remaining refugees used by both, and none of them go through this living Hell unscathed – especially Walker.

From a mechanical standpoint, the game is a combination of third-person shooting and Gears of War style highly-lethal cover based battles. It works, though you’ll find that you’ll usually die incredibly fast if you’re out of cover when too many enemies are on screen. Otherwise, the AI is fairly intelligent, and the ability to command your squad in battle proves to be incredibly useful and adds a light bit of tactics to the proceedings. The gravest sin is that challenge is usually made by just flooding the area with enemies, turning some areas into long slogs of shooting that eventually wear out their welcome. The multiplayer mode, made by another studio and forced in by the 2K Games, is also dead and was considered unimpressive upon release. What makes Spec Ops: The Line so special is not how it plays, but how it contextualizes play and what it means to take part in a violent game like this, and not in the ways you’re probably expecting.

Sometime after the development of the game, Walt Williams went on to write his own book about his experience in the gaming industry called Significant Zero, and it helps explain a lot of what the game tries to do, particularly this quote:

“This stopped being a game the moment we all decided it was cool to be transgressive. If we’re going to present players with deplorable choices, then by God, we have to stand by them. …Art doesn’t embrace the viewer; it grabs them by the arm and drags them into an alley filled with shit and needles.”

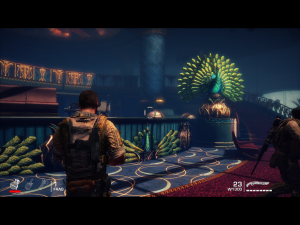

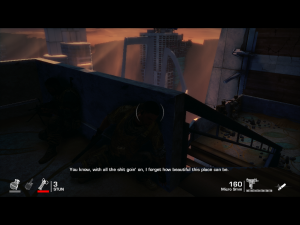

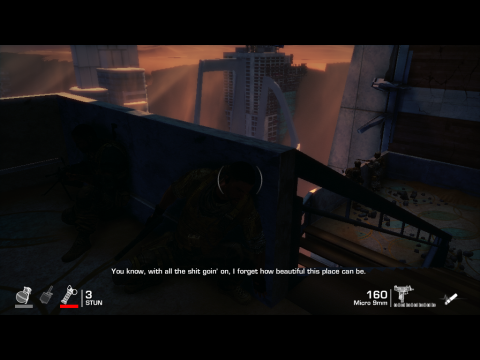

Spec Ops: The Line is aggressive, more so than probably any other game made with a comparable scope or budget, bringing a sensibility that’s usually reserved for indie markets and old 80s PC gaming. After some initial combat and story bits that play out like a COD: Black Ops game, the sheer horror of what has happened to Dubai starts getting shown, from mass executions to white phosphorus bombings. Walker and his squad of quippy video game soldiers become more and more unhinged, with Walker’s mercy kill moves becoming increasingly brutal. Every new broken building hides a new tragic story, and the ending leaves on a bitter, sour, angry note, with the developer provoking the player directly through their characters.

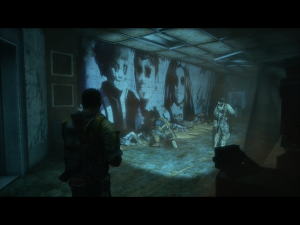

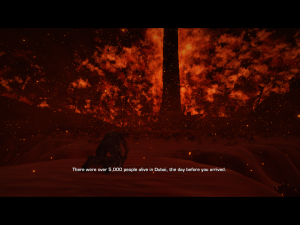

The game is less a judgment of the player for their choices and more a Rorschach blot test, with the decisions you can make having no impact on the ending, except the very last two (one in the last scene before the credits and one in an after credits epilogue). In fact, the game is partly a criticism of morality systems, with Williams using Bioshock‘s little sister system as a negative example in his book. Saving little sisters is good and hurting them is evil, but killing anyone else in the game world is treated as a non-moral issue because there is no impact on the morality system. Spec Ops is a game about committing violent acts and examining what it means to do so. Walker’s team act like generic videogame heroes, with a sense of military moral absolutism and a player-centric “whatever gets me further in the game is good” mindset, and they only make things worse and worse in Dubai, potentially damning everyone in the city to death. Everyone, from the victim to the perpetrators, are damaged by these actions. It even makes a point that you’re not just killing bad guys but actual people, as the 33rd will often chatter with each other about the life back home or the need to find peace wherever you can. They express anguish at horrific acts committed by you. There’s not really a full hero or villain in this narrative, including Konrad and Walker. Good and evil blur with good intentions leading everyone to hell, tossing out the very concept of a morality system.

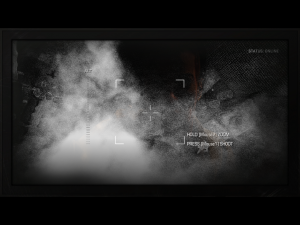

The game’s most infamous scene, the white phosphorus scene, even has basis in reality, based on actual mission footage Williams saw in military school. The fact that it railroads you into this one action of using the substance is often levied as a criticism, but that sort of response is what the game is aiming for. It gives the illusion of a morality system or a choice system, but every choice has no gamified moral value nor sense that it changes the world based on the player’s input. When you’re being mocked in title screens, the game isn’t trying to judge, it’s trying to drag you out of your comfort zone (though this is probably the weakest way it does so). The final confrontation before the epilogue isn’t just between the characters in game, but between the tired developer and the player deciding what they value in this narrative they’ve become absorbed in to get so far.

What makes Spec Ops: The Line such a strange beast compared to other games about games or games about violence is that its goal is not to pass a message, but to make the player think and reflect and draw their own conclusion about themselves and the media they take part in. It’s challenging and layered, suffering only from the bloat of too many thematic tangents (particularly some of the military culture commentary). It’s the complete opposite of commercial art, only made possible by 2K Games’ leadership at the time trying to make their way in the market through more mature and complicated narratives paired with familiar play. By the end of development, Williams was in a deep depression, spending years in creative crunch and ready to move on from his bleak, soul sucking creation, doing small writing work here and there and eventually moving to EA to do writing work for Star Wars Battlefront II.

Spec Ops: The Line may be a tad too ambitious for its own good, but it has a special place in gaming history. Despite being such a large project with so many people involved making it, Williams mark seeps in every single area of the game, his vision fully realized at a great personal cost to himself. It looks at what the AAA game development culture became and questions all of it, and even tries to get the player to question it as well. It’s not just a deconstruction of the military shooter or morality framing in games, its the outright destruction of the idea that the developer and player have no responsibility to what they make and consume, that they have no real connection beyond the developer making something for the player to enjoy. Gaming is an art form, and art has infinite more facets than “makes me feel accomplished.” The Line is one of the few big budget titles to get that, and it certainly left much of its audience different than when it found them. Not all games have to be as challenging as this, but it certainly wouldn’t hurt to change up the ratio a bit.

The sad part of the story is that while the game was a huge critical hit, it failed to get the sales numbers 2K Games desired. On the other hand, that may be for the best. A successful Spec Ops: The Line would have inspired imitators who fail to understand why the game was so beloved, copying only its darkness and aesthetics. This was a product of an absurd amount of circumstances that lined up just right, spearheaded by a man with an intense artistic vision and a head of industry who trusted that vision. He wasn’t trying to set the word on fire, he was saying something he felt he had to say. He helped make this game because he was driven by sheer artistic obsession. We have auteurs in big budget gaming world (Williams even met a few, like Ken Levine), but it’s rare we see something on this scale with such a unified creative vision outside the likes of the Shock games. Spec Ops: The Line is a once in a decade sort of experience, and it’s well worth checking before next one arrives in the 2020s.

The development for Spec Ops: The Line was long and rife with issues, a few detailed in head writer Walt Williams’ book Significant Zero. Three events particular stand out, starting with a late development he lists off in the first chapter.

On the last day of recording with the voice actors, Williams received a message that a helicopter chase that happened late in the game was going to also play at the start of the game, an executive decision he attributes to “the Fox,” a higher up at 2K Games he says was a former vice president at Ubisoft during the early 2000s. He felt this was an insecure way to open the game and ruined the tone he was going for, so he had the voice cast at the last minute record lines he thought of on the spot. This is why Walker believes he’s already done the helicopter chase when you do it again late in the game.

A juicer tid-bit comes from the very start of narrative planning, where the team quickly nailed down the basic premise of an Apocalypse Now riff in a Dubai destroyed by sandstorms. A writer Williams refers to as “Mr. Sunshine” butted heads with him early on over issues like if soldiers should curse (something Williams knew more about after a few years in a military academy). What caused him to be cut loose from the team before things really went underway was how he handled writing a detailed story summary. A month after Williams had supplied him with his basic outlines and a page of important information, he turned in a document that described a game concept even Hideo Kojima or SUDA 51 would do a double take at.

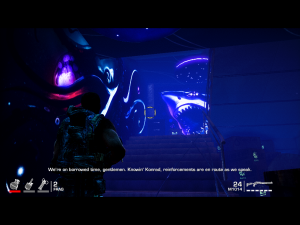

Shark hologram from Singapore’s Underwater World

The main cast shot up soldiers who were eating nachos at a beach party in the opening scene, Konrad was an eco-terrorist trying to use cell phones to capture war crimes he was committing and spread them online in order to start a new world war to save the planet from climate change by wiping out all human life. A spunky New York reporter travels to Dubai to get an interview with Konrad, there’s a hologram zoo, and a turned over boat was now a bar for the parents of all of Konrad’s soldiers. It is not explained how any of these people made it past all the sand storms.

Basic Cheese Nachos recipe from Chowhound

Williams sent this maddening document to the head producer, who only replied with “THEY’RE EATING NACHOS?!?!” Even better, when asked to make a new summary, another month past and Mr. Sunshine just submitted the exact same document again. He did not make it into the final writing staff for the game.

Lastly, and most importantly, the big twist at the end of the game only came about because of publisher interference. Late in development, the Fox felt that the story wasn’t dark enough, as their competition was starting to catch up with the original plans. It took Williams forty-five minutes to come up with the big twist that would re-frame the entire thematic focus of the game, and the Fox adored it. While we tend to blame the publishing side of things for when a game goes wrong, we sometimes forget that their input can also lead to elements in the final game we may love the most. Despite the Fox’s tendency to push the project on too long with new recommendations, he pushed Williams to make the game’s most defining story element.