Sanitarium was developed by DreamForge Intertainment. Not to be confused with the various other companies of that name (and certainly not Dreamcatcher Interactive), DreamForge was responsible for a number of RPGs based on various Dungeons & Dragons campaign settings. Their previous adventure was Chronomaster, which was only mediocre. But fortunately, the developers still knew what they were doing with Sanitarium and were willing to put in the effort to do it right, resulting in a game that easily stands up well next to the creations of more prolific adventure game developers.

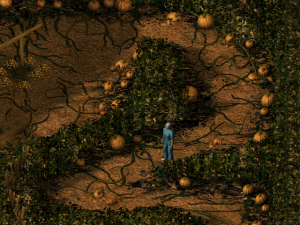

While Sanitarium isn’t readily comparable to other adventure games, it does follow some typical horror and science-fiction tropes. After a suitably ambiguous cutscene of a car crash, the protagonist wakes up in a mental institution, garbed in blue hospital clothes and with his head wrapped entirely in bandages. He has no idea who he is or what he is doing there, which is a problem since the institution seems to have been hit by some kind of serious disaster. It almost goes without saying that he will find himself journeying through various exotic realms, questioning what is real and what is some strange creation of his warped mind, gradually recovering his memories while coming to grips with his own personal demons in time for a dramatic twist ending. It all might sound familiar, but that’s hardly a bad thing, as the game does a thoroughly excellent job of telling a story and establishing atmosphere nonetheless.

It doesn’t take long for the protagonist to remember that his name is Max, and that he seemed to have been involved in some form of medical research before he fell into his current predicament. He also has some unresolved psychological issues about the death of his little sister when he was a child. While he does have some shallow motivations that are overtly presented, there’s never actually too much insight into his character. He just seems to be a pretty nice guy, albeit understandably distressed at the weirdness going on around him. Max barely has any more of an idea of what’s going on than you do, which is all part of the game’s charm. Constantly lurking in the background of his journey is Morgan, who might be the one running the sanitarium and performing horrible experiments on its inmates, Max included – or he might be something else entirely. In the end, everything is explained just well enough to make sense, provided you don’t mind filling in a few of the blanks.

Admittedly, you shouldn’t necessarily expect anything too profound. Max’s psyche just isn’t as overtly tormented as you might think at the start of the game when so much is still shrouded in mystery. Cutscenes pop up at suitably unexpected intervals to reveal more and more of Max’s lost memory, and as the game progresses, you may find the story – and the antagonist of Morgan – to be downright mundane. It is tempting to say that the lack of explicit violence is detrimental to the game’s attempts to inspire fear and horror, but it would be wrong to suggest that violence is necessary when it comes to inspiring such sentiments. It might be more accurate to say that the limited technology available at the time just can’t quite convey everything the designers might have wanted to, though they definitely tried pretty hard.

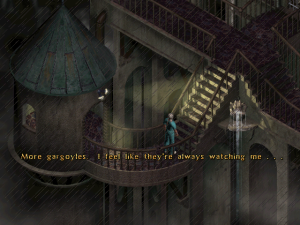

The game is sharply divided into eight chapters, each with its own distinctive title. Each also has its own fairly obvious goal that, once achieved, will catapult you into the next, leaving all your items behind. Alternating chapters are spent in the asylum, or at least something that might be the asylum – you return to a different location within the building each time, and the only thing the parts have in common is that they’re all pretty gloomy, uninviting, and rather Gothic places with weird statues. The other chapters are forays into very different worlds.

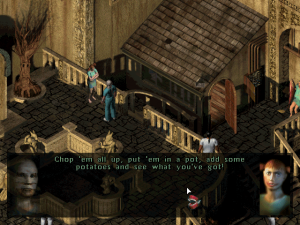

In “The Innocent Abandoned”, you’ll take control of Max in a small farming village where there are no adults to be found, only a group of horribly deformed and curiously contented children. They’re all rather coy about just what happened, though they all keep speaking fondly of “Mother”. Naturally, you’ll be spending some time investigating.

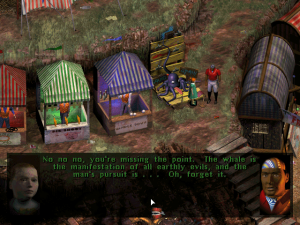

In “The Circus of Fools”, Max suddenly finds himself completely transformed into Sarah, a little girl, perfectly sweet and innocent and, oddly enough, demonstrating no knowledge of Max. She’s trapped on an island with an elaborate but run-down circus, whose dejected performers are all desperately trying to go on with the show despite the presence of an escaped freak that threatens to pick them off one by one. The NPCs are particularly well-done in this chapter, with every sad clown finding his own way to cope with the crisis, with varying degrees of success. Sarah eventually escapes and starts poking around a sepia-toned house filled with glowing, ghostly figures.

“The Hive”, the third trip out of the asylum, sees Max changed into Grimwall, a four-armed Cyclops and one of his favorite childhood comic book characters. He finds himself in a hive of gruesome insectoid lifeforms preparing to massacre much of his race, with the assistance of a traitor named Gromna. It’s all rather reminiscent of Mortal Kombat, or possibly the Zerg from Starcraft.

In “The Lost Village”, the final adventure features Olmec, a holy warrior made of stone summoned to a cursed Aztec village filled with the ghosts of warriors who fell trying to defeat Quetzalcoatl, a king returned from the dead. Olmec has a bit more personality than Sarah or Grimwall, fully aware that his station puts him well above the distressed villagers and is not hesitant to remind them.

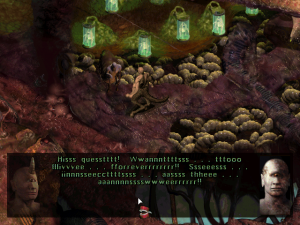

Sanitarium is a very atmospheric game. As stated, you won’t find too much actual graphic violence, but it nonetheless bears a T rating from the ESRB, and you’ll find a good amount of blood, gore, and dismembered bodies throughout the chapters. A sprinkling of religious imagery is also used to some effect. Music primarily takes the form of creepy ambient sounds, often overlaid by the ongoing conversations of nearby NPCs. There are a great many of those NPCs, and even the ones who aren’t at all essential to the plot are fairly fleshed-out with some good dialog. Unfortunately, as they talk rather slowly – especially the ones suffering from some debilitating condition or another, and there are a lot of them – you might find yourself just reading the subtitles and clicking on through rather than listening to their distinctive voices.

Whatever the chapter, the game is largely typical adventure game puzzle-solving. There are some action sequences that stand out rather strongly by virtue of the fact that there are only two of them. They’re both pretty short and not terribly difficult, nor is there any substantial penalty if you mess up. They’re still worth mentioning as they do inject a little suspense and serve their purpose better than an ordinary cutscene would. (A third sequence was planned for the Grimwall chapter but was cut during development; the chapter feels just a bit truncated as a result.) Late in the game there’s also a short maze puzzle of the sort that is rarely welcome in an adventure game, but it is once again over with fairly quickly. The most frequent departure from standard adventure game fare is what the game’s manual calls “blow-up puzzles”, not unlike what you might find in Myst and its derivatives – you zoom in on some mysterious device or another and try to manipulate it via mouse-clicks until you achieve some desired outcome. Yet again, these are no great annoyance and serve to break up the game flow neatly.

The adventure game puzzles themselves are reasonably challenging. The interface is neatly unobtrusive, and almost all of the solutions are entirely logical, even in the game’s more outlandish settings. Problems only arise because occasionally the graphics aren’t as clear as they could be. There are a lot of necessary items that are really tiny, leading to some pixel hunting, but generally the game is fair enough; some things you need to pick up stand out pretty obviously and even twinkle conspicuously. (The game handily contains a manual gamma-correction option that can be useful in some of the darker areas, depending on your monitor setup.) Amusingly, several chapters contain a very literal red herring in one form or another; it never has any purpose beyond leading Max to question what it might be doing there.

Sanitarium spans a whopping three CDs, and the fact that some sacrifices evidently had to be made even to cram it in to that volume speaks to how much content there is. Rather than being hand-drawn, the sprites have a distinctly old-fashioned 3D-modeled appearance about them. Some of them are a little small, and some of their animations are a bit sparse and jerky. The environments are sprawling and lavishly detailed, though the low color depth makes it all look a bit washed-out. They’re also a little bit tricky to navigate at times; most locations contain buildings and other enclosures whose interiors become neatly revealed through a cutaway view when you approach the entranceways. The whole effect is a bit reminiscent of some of the isometric RPGs of the era (such as Fallout or Baldur’s Gate).

The aforementioned FMV cutscenes are also plentiful enough to take up a good chunk of Sanitarium’s considerable size. Like the sprites, they’re done with puppet-like 3D models, but while the characters move stiffly, they at least move convincingly. They show some very effective use of perspective and filtering effects, but unfortunately they’re marred by rather ugly interlacing – probably due to space constraints again.

While the speech quality also takes a hit, encoded only at 22 kHz, even a higher sampling wouldn’t remedy Max’s voice. His exaggerated and unrealistic mannerisms bring to mind not so much William Shatner as Dave Seville from Alvin and the Chipmunks. Even for someone of questionable sanity it’s a bit over the top. Everyone else sounds quite appropriate, but you’ll be listening to Max a lot. It’s enough to make it difficult to sympathize with his plight.

As you start to make sense of the denouement and Sanitarium’s ending credits play, you are treated to what ought to rival Portal’s “Still Alive” for the most amusing video game ending credits music. It’s a brilliant mashup of various voice samples from throughout the game, and strongly instills that unfamiliar sensation that the game’s developers really cared about the game they were working on. Sanitarium may not necessarily be the incisive glimpse into one man’s complex, tortured soul that it hopes to be, but it is this sense of diligence that pervades the game as a whole.